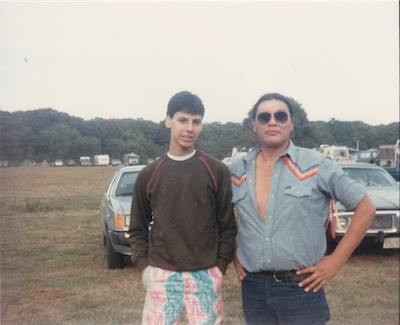

Jim Genia

Fiction

Jim Genia—a proud Dakota Sioux—mostly writes nonfiction about cage fighting but occasionally takes a break from the hurt and pain to write fiction about hurt and pain. He has an MFA in creative writing from the New School, and his short fiction dealing with Indigenous themes has appeared or is forthcoming in the Zodiac Review, Electric Spec, Sage Cigarettes Magazine, ANMLY, Indiana Review, and more. Follow him on Twitter/Threads @jim_genia.

Thiohnaka (Home)

Henry spends the night drinking with his brothers in the kitchen, the empty cans accumulating on the table, on the counter, on the floor, until the men grow incoherent and violent, and eventually pass out. In a room down the hall, Henry’s young wife and son lie in bed, bitter and ignored.

Henry spends the night drinking with his brothers, because this is what you do when you return to the reservation after your father moved you away a dozen years ago, back when the Indian Relocation Act was an enticement and a promise, and certainly not a death sentence.

It’s 1973, and now that their father has passed, Henry—the chaska, the firstborn—is the new patriarch. He’s 24, and wants only what’s best for his family, so he’s brought them all back to South Dakota. To the home he remembers.

Henry spends the night drinking with his brothers, and when he wakes on the floor, his head throbs. The back door is open, revealing a cold dawn sky over endless fields. The draft leaves him shivering.

On a small transistor radio, the low, garbled voice of a newscaster. President Nixon and Cambodia. The American Indian Movement surrendering at Wounded Knee.

Around him: crumpled cans, discarded pull tabs, cigarette butts, and fragments of angry conversation.

Around him: his brothers—snoring in a chair, unconscious with a head in an arm, asleep on the floor. Tangles of long hair everywhere.

Henry takes in the details, and he thinks of how, after 12 years away, the kitchen seems much smaller.

Henry takes in the details, and sees someone he doesn’t recognize, sitting with his back against the icebox.

He’s short but broad shouldered, with bare, muddy feet and wrinkles on his face. Though a protruding, neanderthal brow conceals his eyes, Henry can tell the stranger is watching him.

At first, Henry isn’t sure he’s real.

“Hm,” says the man, his voice a rumbling bear. “You shouldn’t have come back.” In a meaty fist, an open can of beer.

~

It’s a simple house, with two floors, indoor plumbing, and a thick cast-iron stove meant to swallow up firewood in exchange for precious warmth.

The driveway is long, and the woods between the road and the yard are home to deer and rabbits.

There’s a creek, alive with fish and beavers when not frozen over.

A neighbor’s grain silo towers in the distance. Abandoned farm machinery. Memories of Henry’s father on a tractor.

Memories of being happy.

In the ground by the back door lie four siblings, newborns whose brief, fragile lives lasted only hours because the nearest doctor who might’ve cared was too far away. The flowers planted to mark their resting places have long since been claimed by harsh winter after harsh winter.

Once he fills the pantry with commodities and cleans the rifles hanging by the door, Henry muses, it will be as if they never left.

“Hm,” says the man, his voice a rumbling bear, and Henry thinks of the ghosts of Sica Hollow, the spirits who live in the trees, and the serpent of Lake Traverse. “You shouldn’t have come back.”

Henry and his brothers do their best to clean up, fumbling with dishcloths and a broom when their mother comes downstairs, her face wrought with disgust and disdain.

Henry and his brothers do their best to clean up, as their mother goes out to the car with two of her daughters in tow. They head off to town to buy groceries.

On a small transistor radio on the counter, the garbled voice of a newscast. President Nixon and Cambodia. AIM surrendering at Wounded Knee. Occupations and sieges. Russell Means and the FBI. Though the Pine Ridge Reservation is hundreds of miles away on the other side of the state, it feels as if the events there could easily happen on the Lake Traverse Reservation, their reservation. It feels as if it could be happening right outside, the US Marshals and the National Guard hiding behind the neighbor’s grain silo, massing near the abandoned farm machinery.

Henry and his brothers do their best to clean up, and Henry’s wife—a waifish, fair-skinned 19-year-old from Long Island—demands attention. This isn’t her world, she says. These aren’t her people, and the exotic boyfriend she fell in love with when she was 16 is too preoccupied now. Also, she adds, what about their son?

Henry opens his mouth to answer, but before he can do so, his mother and sisters return.

They’re hysterical.

When they walked out of Stavig’s, a group of white men from the bar across the street took their groceries and threw them to the sidewalk. Shouted curses. Called them filthy Indians and said they weren’t welcome around here.

It’s 1973 and Henry only wants what’s best for his family, but the world has other ideas.

In a flash, Henry and his brothers are out the door and cramming into their cars. Hunting knives in sheaths. A rifle. A .22 pistol. Frustration and anger. Righteous rage. In times of revolution and uprising, these are the things a res Indian carries.

Their tires kick up dirt as they speed down the driveway.

On their cars, yellow New York license plates.

~

When Henry was young, his mother talked of a man in a rumpled suit who would come to Sisseton with a thick ledger, and Indians would go into town to have their names recorded. The Dawes Rolls, which ensured that the Indians with farms could keep them, and coexist with the white folk who paved the roads and built the tiny movie theater and the bank on First Avenue.

When Henry was young, he attended the one-room schoolhouse, which was warmed by a potbelly stove tended to by the town drunk, a kind elder who could change into a buffalo or an eagle.

When Henry was young, his father—a brilliant man who aspired to more than the res could offer—gathered up his wife and ten children and took them east. Henry’s father was a scientist, lured to work in a laboratory that eventually killed him.

Henry is 24 now and the patriarch, and it was his decision to move everyone back to the farm in Sisseton, where his mother grew up and he and his brothers and sisters were born.

He just wants what’s best for his family.

Henry and his brothers return, giddiness on their faces and their hair long and wild.

In the kitchen, they excitedly recount what happened.

They describe rolling into town, storming into the bar across the street from Stavig’s, and demanding to know which cowardly son of a bitch assaulted their mother. Warning the assembled white folks that if anyone messed with their family, they’d regret it.

With cigarettes in hand and wide grins, they describe how when they turned to go, one of the white folks charged, and Henry spun around and hit him with the butt of his pistol.

How the man fell clutching his head, and the white folks were real quiet after that.

Wide grins grow even wider.

On their mother’s face, disgust and disdain.

Henry’s wife shakes her head, her son on her hip.

The sounds of engines, of cars accelerating up the long driveway, and it’s suddenly clear the story isn’t quite over.

Henry peeks out the window above the sink and sees a pickup truck and a Cadillac, kicking up big clouds of dirt as they approach. Sees angry white faces. The barrels of rifles and shotguns.

He screams for everyone to get down and leaps on his wife and son, knocking them to the floor.

Bullets fill the air, shattering glass, splintering wood, poking holes in a tin of flour and in the door to the icebox.

~

“Hm,” says the man, his voice a rumbling bear, and Henry thinks of the wanagi of Sica Hollow, the canoti in the trees, the mniwatu of the lake, and other creatures of legend. “You shouldn’t have come back.”

Henry’s head throbs, and the cold draft from the open back door makes him shiver. “Thiohnaka,” says Henry. “Home. This is our home.”

In the man’s fist, an open can of beer. He brings it to his lips, tilts back, and drinks deeply until the can is empty. The sound of it crumpling in his hand, and he tosses it aside.

The brother snoring in the chair coughs, shifts, and resumes snoring.

“Hm,” says the man, and he shakes his head. “No such thing. Not for you.” He rises—too quickly and too nimbly for someone so small, and it makes Henry uneasy. But the man walks to the door, his bare, muddy feet leaving tracks on the faded linoleum, and it’s clear he’s leaving. “Even your father knew that,” he says, and he’s out the door and gone.

~

The pickup and the Cadillac circle the house twice, guns blazing, before Henry and his brothers rise and return fire, a fusillade that fills the house with the stink of gunpowder. Just as quickly as they came, the white men leave, their engines roaring and tires screeching as they race back down the driveway.

On the transistor radio, talk of Nixon and Watergate. The arrest of Dennis Banks, and the FBI’s manhunt for other AIM activists and fugitives. It’s 1973, and though Congress has lifted the ban on Indigenous languages being spoken in boarding schools, it’s still a perilous time to be an Indian.

Henry and his brothers do their best to clean up, while their mother mumbles something about how this never happened when their father was alive, and certainly not when they lived out east. She retreats upstairs, daughters in tow.

Henry’s wife—the waifish, fair-skinned 19-year-old from Long Island—demands attention. This isn’t her world, she says, her voice fraught with desperation and fear. These aren’t her people, and the exotic boyfriend she fell in love with when she was 16 is dangerous now. Also, she adds, what about their son?

Despite being only 24, the death of his father has left Henry the head of the family. He wants only what’s best for them, and what’s best for them can’t possibly be found among the whites who lured his family away from where they belonged, among the whites who took his father.

So Henry spends the night drinking with his brothers in the kitchen, the empty cans accumulating on the table, on the counter, on the floor, until the men argue that none of them want to be there. Until they grow incoherent and violent, and eventually pass out.

Because this is what you do when you return to the reservation and find it doesn’t want you.

Henry spends the night drinking with his brothers, because this is what you do when your people don’t truly have a home.

“ Aside from the magical realism and mythical creatures, the events depicted in this story are true. Moving back to the reservation in 1973 was pretty problematic for all involved. But in that time of resistance, when it came to Indigenous rights and fighting assimilation, anything to do with Native Americans was pretty problematic. Still is. ”