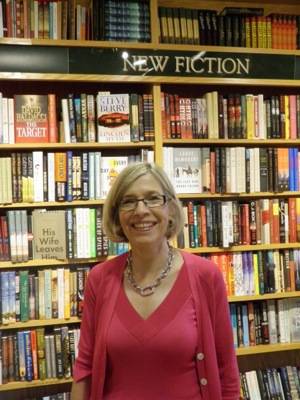

Shirley Fergenson

Contest - 3rd Place

Shirley Fergenson is the literary fiction specialist at The Ivy Bookshop. This piece is part of a collection of linked stories she began during her Masters in Fiction Writing at Johns Hopkins University. When she is not reading, writing, or selling, she rides her bike and gardens. She lives in Baltimore with her husband, whom she met and married in the aisles of The Ivy.

How to Leave a Garden

“We must cultivate our garden.” Voltaire

You may never need to know this. I certainly didn’t think I would. But in the name of good sportsmanship, I pass this on.

First you cry, but not near the delphiniums. Their melancholy, stooped, blue spires in no way advocate for their tolerance of salt. Their downright finicky need for full sun, cool temperatures, high humus content, and a neutral pH, should argue against their presence in the garden at all. But it doesn’t. You probably agree. Some things are worth fussing over.

The young plumbagos, on the other hand, wear their baby blue crowns like they’re expecting to be stepped on, spreading willy nilly past defined borders, low to the ground and underfoot. The more mature plumbagos dare you to remember that their prickly brown seedpods were once as soft as the youngsters they replaced. A few tears won’t kill them. Delicate and hardy, I leave them both to you, to fail or thrive without me.

For as many years as it has taken the wanton wisteria to overwhelm the stalwart silver maple, unlucky enough to have been planted too close, I have been friend, midwife, and undertaker to these four acres. If I had done half as well in the house with Richard, I might be there yet. Give me a chrysanthemum, and I know just when to stop pinching back to get the best bloom: a skill I never mastered with my husband.

So: I leave Richard; I leave the house; I leave the garden.

The boxwoods, thank goodness, can take care of themselves. Study them to see how well they manage: seventy years old and still able to regenerate after a hard pruning. The last time I cut out so many yellow and orange cupped-leaf branches—phytophthera infestans the extension agent said after I sent him a sample—I wondered if maybe it was finally too much. But it wasn’t. The next spring tiny green fingers, sprouting everywhere there was a cut, tickled me back when I ran my hands over their innocent exuberance.

You can practically take the ferns for granted, but don’t. Their brave fetal push through last season’s seemingly impenetrable carpet of leaves defines hope. Every spring be amazed that their fiddleheads are tough enough to break through. They hoard their strength in tight rolls, and only unfurl to feathery delicacy when they are well past the hardship of their birth. Take note.

If the ferns aren’t compelling enough, look to the peonies. Pale, fleshy tips break cover in early spring and break hearts: they are too pink to survive. An oblivious foot, an unrestrained rake or a too heavy hand at weeding reduces the potential of the most sanguine nib. But, like the ferns, they take their strength from their fierce self-centeredness. Only when their heads reach above foot level do they forgive their enemies, and unfurl with mitten-leafed optimism.

And, as if they wouldn’t be invited back without a gift for the hostess, they offer up creamy, fat buds, so heavy they can barely lift their heads: certainly too heavy to open by themselves.

So they call for help. Ants.

Do not spray.

The sticky nectar is their reward for releasing a mille-feuille of silky petals. Be prepared when the sun-gold stamen draws you ineluctably down to inhale. There is no aroma, except maybe that of the lily-of-the-valley, which is more seductive. Tuck a bloom behind your ear. Richard does not like store-bought perfume.

I leave them to you because I cannot grow where they are. I thought if I nurtured them, they would return the favor. If I didn’t cut the daffodil leaves until their bulbs resorbed the lifeblood for next year’s flowers, they would shield me. If I cut back the bearded iris in the summer and carefully pulled dirt away from their rot-prone, tuberous chests, they would stand guard for me the following spring. If I divided the astilbes so their pink, red and white plumes had room to toss their pretty heads like young girls who know they are being watched, they would warn me, somehow. But they didn’t. I may have been asking too much. It doesn’t matter.

I have a confession: there’s no excuse for what I did to the clematis. Up to the very end, I lied to myself. Why did I plant five new varieties on the sunny side of the fence, when I wouldn’t be around to keep their feet cool with a ground cover? So what if I tied their frail leaders, oh so tenderly, to the uprights? They needed to be under-planted. I knew that. And I acted as if I had all the time in the world, that the searing sun was months away. And it was. But I was long gone by then—except for stealth visits when I knew Richard was out.

They burned. Like babies left out without their bonnets. Crisp. Brown.

I don’t deserve to be forgiven for that. But somehow the cosmos and impatiens, one-season annuals, don’t hold a grudge. A trick neither Richard nor I ever learned. They reappear on their own in heavily mulched beds, like forgotten deposits growing unexpected dividends. You may wonder why the rest of the annuals stay missing. In my own defense, I left before Mother’s Day, the safe frost-free planting date. Weeds have filled in for the zinnias, ageratum and salvia, like unrehearsed understudies. I’m embarrassed to leave such a mess. If you don’t mind a suggestion, think about sweet alyssum next to the volcanic rock border. It looks like fairy dust.

The beech was not my fault. The drought was so severe, no matter how many times I moved the hose, the hydrangea or the weeping cherry, or the kousa dogwood stayed too thirsty. The tree surgeon said it was already stressed, that the lindane, toxic as it was, could not recall the invitations the beech had sent out. The bark beetles feasted. There was nothing to be done but use the logs in the woodstove.

That should have been the end, but it wasn’t. When the beech came down, the yellowwood scalded from too much sun hitting its previously shaded, forked crotch. And the pachysandra, like supplicants in a holy temple of dappled shade, suddenly destroyed, couldn’t shrivel fast enough. A once lush bed shrank to a few hardy survivors. I’ve seen some new offshoots this spring. It may come back yet, if you’re patient about weeding the vacated spaces; give the new life a chance to take hold.

Inasmuch as I chose to leave, I admit I’m surprised how quickly Richard has replaced me with an exotic variety. I wonder if you’ll thrive in foreign soil. I hear you’re an accomplished gardener in zone four, but I could probably still give you some pointers for zone seven: how to conserve moisture during the dog days—mulch deeply around the magnolia; how to send roots deeper and wider for nourishment—deep water the sunflowers until they refuse to be uprooted at the end of the season; how to plant next to a sympathetic, concurrently blooming variety—choose a bird-magnet mulberry tree, as a willing martyr for the sour cherry.

But you’ll probably want to find out for yourself. You’d mistrust my motives, anyway, as if I’d leave out the secret ingredient in my anti-damping-off potting mixture.

Smell, feel, and taste the dirt, so if you ever have to leave, your nose, fingers, and mouth will remember. There is no substitute for torn-cuticle, broken-nail gardening. You know that. You’ll worry holes with your index and middle finger through every pair of gloves you buy, no matter how durable the label promises. You’ll grind through the knees of your pants. And don’t become too attached to your tools. You’ll lose your trowel in a frenzy of finishings whenever Richard calls you away from your seedlings to tend to him.

Let it be the morning glories rather than the delphiniums that draw your tears. A bit of salt won’t hurt them. Their frail blueness belies their tough, sweet potato vine ancestry. Maybe you already know that the seeds require a twenty-four-hour soak and nicking of their hard seed coat before planting, that their jack-in-the-beanstalk growth pattern is splendid for covering up eyesores.

But there is something else. Someone should warn you.

The most dangerous time will be mid-morning when their pale throats are open so achingly wide, as if their honest vulnerability could stop the inevitable. In an hour their heavenly blue bells will be twisted shut; in a day they will be litter off the vine to be gathered for compost.

Gardeners learn best from experience.

A final tip: it was never Eden. And you don’t really need four acres. Window boxes planted with dusty miller, trailing vinca, and blue salvia can be quite lovely, viewed from a dining table set for one.

And if you add lantana, expect hummingbirds. Call it a party when they sip nectar from their tiny, ruby and amethyst pitchers.