TELEPHONE

Project

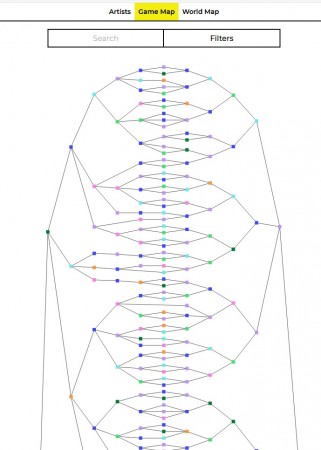

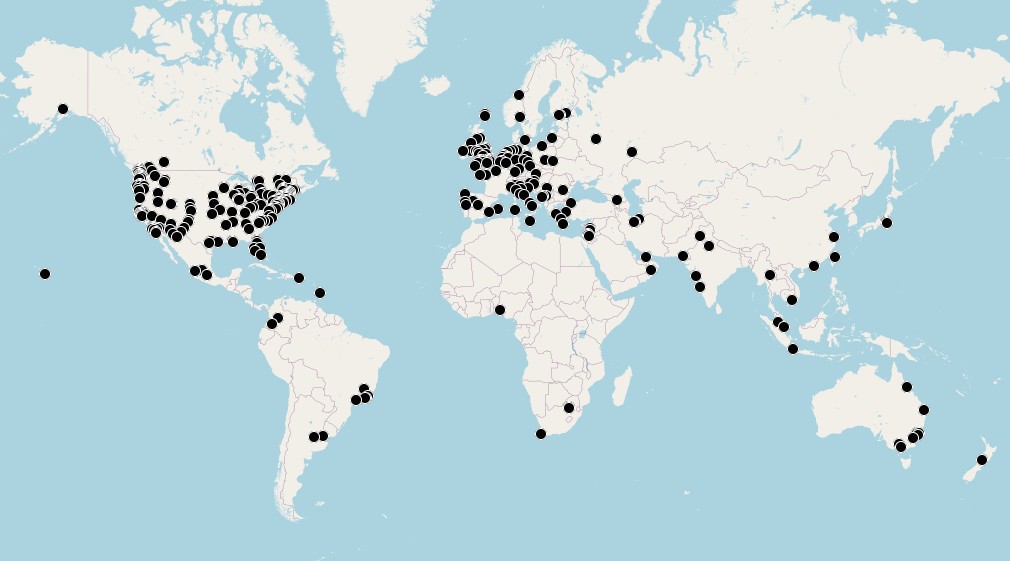

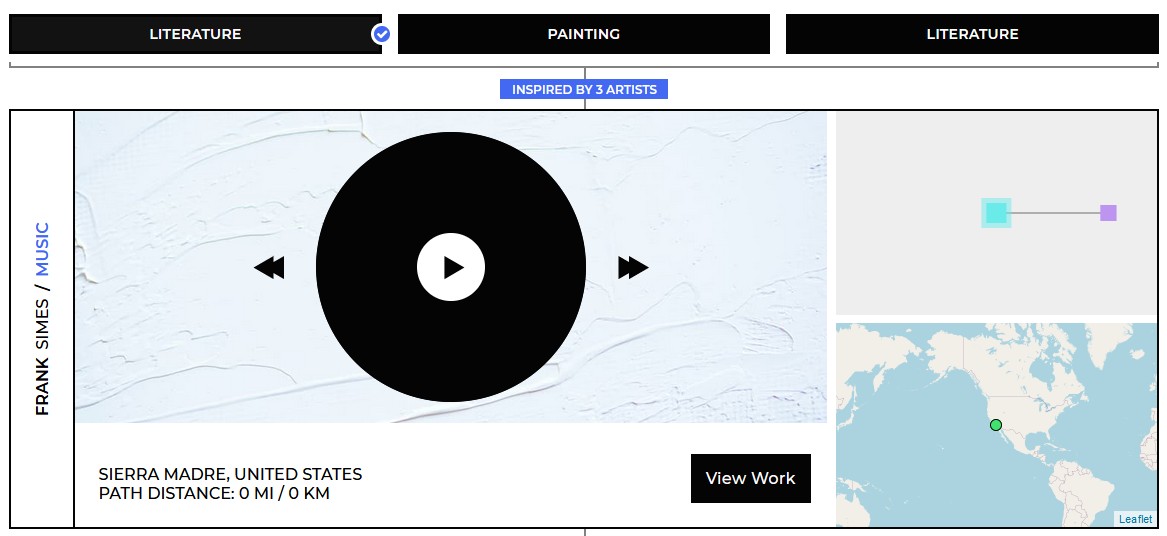

Remember that game you played when you were a kid? Telephone? The TELEPHONE project is a game too, but on a grand scale. This is no game of giggling kids whispering a sentence around a circle. The TELEPHONE project, directed by Nathan Langston and designed by the dedicated (and all volunteer) project team, connected over 900 artists of many kinds (including writers, of course) in 72 countries. The project started with one message, passed through all the artists, branched out exponentially, then reversed and concluded with a single artwork. Confused? See the game map. Better yet, jump into the game and begin your journey. Get lost. Start here.

The TELEPHONE Project

The TELEPHONE Project, created by Nathan Langston and the project team, went live on April 10, 2021—and we want to shine a light on it, because it’s an incredible ekphrastic experience. TELEPHONE began with one message that was passed on to artists who created artwork in response: sculptures, music, literature, music, and film & dance. In turn, their art was passed on to others, branching out into the web you see below. Over 900 artists in 72 countries. A web of art—creative writing, paintings, music, dance, and more—that you can lose yourself in for hours. Not exactly a couple of tin cans connected by a piece of string. The technology here is beyond my comprehension. Fortunately for exhibit visitors, the vision and tech know-how of Nathan Langston and his team—with some help from 900+ artists around the world—made such a cool thing possible.

The Baltimore Review connection? We love art! We love ekphrastic art! We love games—and the game of Telephone has been around for a long time. (Fun Fact: The winner of our summer 2020 flash fiction contest was “Telephone” by Cara Lynn Albert.) When Nathan Langston emailed us in May 2020 about recruiting people for the project, we put out a call to hundreds of writers, including a few arts organizations, and it looks like many agreed that playing the TELEPHONE game during a pandemic would be an excellent thing to do. The project includes a good number of BR contributors and writer friends (including Deesha Philyaw, who won the 2021 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction), an essay on “Metaphor in Art and Science” by BR staff member Michael Salcman, and a whole lot of behind-the-scenes website work by BR webmaster Matt Diehl.

And because we think this is such an amazing exhibit, we will continue to get the word out and support the TELEPHONE team in any way we can.

We hope that you’ll pass the word along, too. No need to whisper.

Experience TELEPHONE here.

Q&A with Nathan Langston, TELEPHONE Director:

How would you like to see the project impact and inspire other artists around the world?

Firstly, I hope that TELEPHONE can serve as a reminder that something beautiful can be created in a very dark time. For me, the highest purpose of art is as a form of medicine, and its relevance comes into sharp focus. I’d like this game to remind our colleagues and collaborators that when things get very bad, artists go to work, like frontline workers of the soul.

Secondly, we’re still in the infancy of the internet, one of the largest

historical advents of our age. I hope more artists will begin to approach the

internet as a medium, like photography or sculpture. It’s like with the motion

picture, invented by Edison and Dickson in 1888. Think of how rudimentary

movies still were by 1910! An Alfred Hitchcock movie would have been

unimaginable then. Sound didn’t even get added until 1927. That’s where we are with the Internet. It’s a brand new medium that no one knows how to use. So

exciting!

Do you imagine TELEPHONE inspiring ekphrastic games in schools for young artists (and more play time for adults, too)?

Absolutely! I dearly hope that happens. Capitalism primarily rewards

hyper-specialization. The easiest way to have a lucrative career is to be the

foremost expert in an extremely niche field of knowledge. The same goes for

artists, too. This isn’t to disrespect specialists. If I’m getting a surgery, I

want an expert! But specialization can lead to compartmentalization and tunnel

vision. Often, a problem in one discipline has already been solved in another,

but they’ll never know unless they talk to each other.

I think

ekphrastic games at all levels of pedagogy and in all disciplines, not just

art, would encourage the mental flexibility to recognize latent connections

between very different compartments of knowledge and make us more able to

adapt and respond to unforeseen circumstances. This should be a primary goal

for all schools.

With my 5-year-old, we play a simple form of it

called Connections. We start with anything, maybe the stars. What are the

stars connected to, I ask? The moon! What’s the moon connected to?

The ocean! What’s the ocean connected to? Fish! And so on.

We go as long as we can and sum it up at the end.

“The stars are connected to hamburgers!”

Can this project create a better awareness of other cultures?

Maybe. I think a different form of the game could do a better job of that than

ours did. But we did at least connect people from very different places. For

example, the headline currently is about the United States imposing sanctions

on Russia for hacking. But we have friends in Moscow who played this game

with us. We have artistic collaborators in China. TELEPHONE includes fellow

artists in Iran.

Having lived the last four years under the

previous administration, I feel like I learned a thing or two about living

with a government that doesn’t necessarily do a good job of representing my

experience as a person or an artist. Same goes for everyone everywhere.

Is the project attempting to stir an interest in unfamiliar art forms and the connections between different art forms?

Yes! Like industry and education, these forms get into weird silos. The

dancers live in their world. The musicians have their own scene. The visual

artists keep to themselves. The poets have their own esoteric community.

Again, it isn’t to disparage celebrating these forms on their own. But some of

the most amazing times in art history (Black Mountain College, Bauhaus, Paris

in the 1920s, etc.) are times when all the forms come together to

cross-pollinate.

And why shouldn’t they? All the forms rely on the

senses. All the forms share various expressive techniques like rhythm or hue

or shape. All art forms rely on the cognition of the human brain. But possibly

more importantly, getting all the forms together just makes for much better

parties!

What are your dreams for the TELEPHONE exhibit going forward? In particular, what can you envision for the time when people can be physically together?

In the short term, we’ll be “weatherizing” the exhibition, preparing it to

stay live for as cheaply as possible over the next two decades (at least) as a

time-capsule from this strange time. Eventually, when it becomes safe, a lot

of effort will go into connecting these artists in person, both locally and

internationally.

Over the long term? Gosh, I’m too tired to

envision it right now. It could become an actual scientific experiment, using

a more sophisticated tagging method of completed works. It could become

totally automated so as to do an exhibition with 100,000 artists. There are

all sorts of other strange game shapes that could be employed other than the

last two we used.

Also? This project doesn’t really belong to me.

It belongs to all the artists and the people who made it, so it’s not entirely

up to me. It’s very possible that other artists, teachers, and scholars will

steal this concept (the way we stole it) and TELEPHONE will get translated

into something new and beautiful that we never imagined.

Nathan Langston graduated from University of Oregon with a focus in poetry. He has toured to almost every US state with bands and helped start both Ballet Collective and Satellite Collective in New York, composing scores for interdisciplinary works of ballet and modern dance. Nathan created and ran the first game of TELEPHONE, published in 2015, and initiated the second game in March 2020. He currently works as a software designer in Seattle, where he lives with his two boys, and continues to compose both poetry and music.

Here, you can read his 2019 work, “I Need You To Tell Me Everything.”