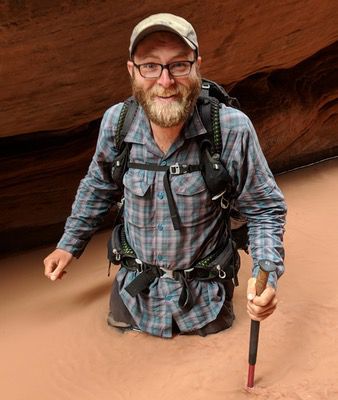

Kyle Stolcenberg

fiction

Kyle Stolcenberg is an MFA student at Southern Illinois University. This is his first published story.

Twenty Miles to Toad River

A long day’s drive up from Edmonton and the truck dies climbing a hill. The boy wakes in the passenger seat as his uncle pulls on his snowsuit and his parka. Nobody’ll be by here ‘til mornin’, the boy’s uncle says. There’s a service station a few miles up the highway. He gestures out the windshield. The boy rubs his eyes. Let’s hook up the team. Gonna go get us some help. His uncle pulls his bunny boots from behind his seat and laces them up. He works by the light of his headlamp. His fingers are calm but quick. The boots are the color of old snow. The boy sees them—heavy and stiff, but nothing warmer—and knows that his uncle is scared.

Already the windows are frosting.

The boy’s uncle arranges the velcro nameplates of twelve dogs on a clipboard then opens the door and sets the board on the windshield. He shuts the door quickly, but the cabin is no longer warm.

The boy dresses and steps outside. His first breath freezes the hairs in his nostrils, and he coughs. He points his headlamp at the thermometer screwed to the truck. It reads forty below. He pulls his neck gaiter up to his eyes. He feels the winter in his chest.

The truck’s a big diesel pickup with the bed pulled off, replaced by the plywood dog box painted white and forest green. Two rows of five little doors on each side of the truck. A door on the back of the box to an alleyway down the middle where the dog food and gear is stored.

Behind the truck, the ice fog is finally dissipating. The last lingering proof that the engine once churned—that someone has been out on the road.

The boy checks the clipboard and opens a box in the bottom row. Two dogs are curled together inside. They seem surprised to be disturbed at this hour; it takes a moment for the boy to coax the first dog out and clip him by a short chain to the bottom of the truck. The boy closes the door as the second dog prepares to leap out. Sorry, Tex, he says. You don’t get to play Balto tonight.

~

When six dogs are down on his side of the truck, the boy walks to the edge of the road and pulls off one glove. It’s a project undressing enough to pee: zipper down the coveralls, unbutton the pants underneath, pull down the front of the wool leggings. With each layer he feels the air rush in, closer to his skin, but with the last layer there’s always less cold than he expects. A sheet of steam rises all along the stream of his urine and shimmers in his headlamp’s white glow.

He returns to harness the dogs. Each of them stands with one foot in the air, protecting their heat from the ground. One stands up with front paws on the dog box, hoping to go back inside.

The boy’s uncle tosses booties and red jackets on the ground next to each dog. The boy removes his gloves to fasten the velcro on the booties. He swings his arms and shoves his hands in his pockets after each dog, but still his fingertips tingle and sting.

The sled is anchored to the front of the truck with a line and quick release. The boy and his uncle hook up the dogs. There’s not enough snow on the road to set ice hooks. The dogs slam into their harnesses, trying to pull the truck up the hill. Their barking is the only sound in the world.

The boy’s uncle stands on the sled. I’ll have to take ‘em slow on the pavement, try to save their pads, he says to the boy. The wheel dogs are frothing. One of them snaps his tugline. The boy grabs another line from the sled’s handlebar and rushes to secure it. His jog is clumsy in his boots. His breath is quick and hot and held against his face by the neck gaiter. The fleece moistens and freezes stiff. He turns off his headlamp. His uncle’s shines over the team. I’ll be back soon. Few hours.

The boy’s uncle pulls the quick release—ALRIGHT!—and at once the dogs are silent. Their breath rises and hangs over the team as they are able, finally, to pull. The sled clacks and squeaks; the boy’s uncle stands on the brake and it grinds into the road, screeching, and keeps the dogs from stretching into a lope. The team crests the hill and disappears into the sky. The boy stands staring at that place—where the dusty slash of the Milky Way touches the highway—until his toes hurt.

Even without wind, snow writhes like smoke in veiny tendrils on the surface of the road.

The boy moves the remaining dogs to the most central boxes, rearranging so no dog is alone. Then he opens the back door and climbs into the alley, hoping the dogs will heat him through the thin plywood walls.

He stoops in the alley, crawling beneath the waxed sled runners hanging from the ceiling, climbing over coolers full of frozen beef and liver, buckets of poultry fat, bags of various powders: bone meal, Glycocharge, ground psyllium husk. He knocks over a trash can lined with an old bag of dry food; frozen dog poop, picked up all day from parking lots, falls out and scatters onto the floor of the alley.

Everything is too cold to have a scent.

The boy uses an ice hook to slice the baling twine from the fresh dog-box straw and makes a nest in the center of the alley. His toes still hurt. He pulls his beaver mitts over his gloves.

~

As the cold creeps in, the boy sleeps. He shivers on the straw. He dreams he is a raven swooping over the team as it floats through the boreal forest. He flies ahead and perches on the spindly top of a black spruce. He watches the dogs run past. He knows they are not wolves, knows they will not lead him to food, but still, as a raven, the boy follows them.

He is curled tight on his side with his arms tucked against his chest. Soon the shivers seem like convulsions. His hip burrows through the straw to the plywood floor and he feels its cold spread into his legs. He can’t rearrange the straw under him without uncurling, so he doesn’t, and soon his hip aches from the pressure. He lets his teeth chatter a few times.

The boy feels the forest spreading beneath him. The wild of it keeps him aloft. But he knows those leagues are unknowable, so he does not look there. He looks only at the dogs gliding silent and the warmth of their breath and the thin slice of white they follow through the dark, and he follows them.

In the morning, hours before daylight, the boy hears a truck pull up next to his. He hears boots crunch around the cab and call Anybody here? The boy curls tighter and tries to fall back asleep. The dogs don’t bark, and soon the man is gone.

“ A couple years ago I answered an internet ad for a job as a sled dog handler and flew to Fairbanks on a whim. I learned that mushers tend to be competent and intelligent and altogether unlikely to make the sorts of mistakes that lead to typical adventure narratives. This story wonders why that has to be the case. ”