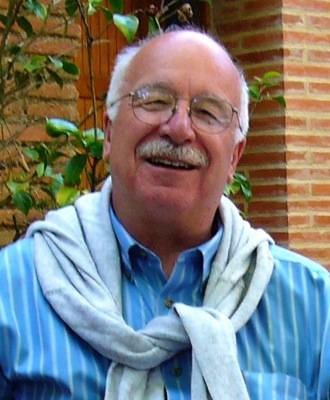

John Goulet

Fiction

John Goulet grew up in Boston, Colorado and Iowa. He attended St. John’s University, San Francisco State, and the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. After serving in the Peace Corps in Ethiopia, he returned to take a position at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, where he is currently Emeritus Professor of English and continues to teach courses in creative writing. Goulet is a published short story writer and novelist (Oh’s Profit, William Morrow; Yvette in America, U of Colorado Press). His stories have appeared in numerous journals, magazines and anthologies, including Carolina Quarterly, The Beloit Fiction Quarterly, The Literary Review, Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Cutbank, The Massachusetts Review and Norton’s FLASH FICTION FORWARD.

The Hyena Man

There’s a place in eastern Ethiopia where a man feeds hyenas by hand. He’s called the Hyena Man. For a few dollars he’ll give you a stick with some meat on the end, and you can feed the hyenas, too. This takes place at night, near a big bonfire. The hyenas come in from the dark and growl and grab the meat and go off. I was on a tour with three other ex-Peace Corps volunteers and we all thought it would be an interesting thing to do, feed the hyenas, but afterwards we felt let down, we didn’t know why exactly. This was about ten years ago when I went back to that splendid disaster of a country to see what had become of it since I’d taught school there in the sixties.

There’d been a Hyena Man back in the sixties, a different one of course—the Hyena Man is a title, a station in life, a career, and doesn’t refer to a specific individual—but I worked in a different part of the country and never got to watch him in action. At that time I was involved with a woman who taught in a small village in coffee-growing country. Every other weekend I’d get on the bus headed south from the capital. These were big, new German busses, filled with quiet, elegant men clothed in rags, and slender women who dressed their hair with rancid butter and during the occasional rest stops spread out their wide skirts and stooped to pee. And chickens and goats. It took about eight hours to get to the T intersection and the narrow, rutted path that led to my friend’s village and by that time it was around midnight.

There was no Hyena Man in that part of the country, but there were plenty of hyenas. No sooner had the bus rumbled off—tiny headlights disappearing down a shadow—than they started welcoming me. I’m not a mimic and can’t do a hyena howl, but I can still hear those babies, fifty years later, the eerie symphony that followed me in the dark the twenty-minute walk from where the bus left me to my friend’s house. I think I was uneasy, but not scared. I wasn’t thinking of the hyenas’ hunger and how they must have been watching my flickering flashlight beam and listening to my footsteps on the path. No, I was thinking of the woman who was waiting for me in the dark village (the electricity went off at nine o’clock). I was thinking of the woman’s bed with its legs immersed in water-filled buckets to keep off the coffee spiders, and the woman herself lying on that bed naked. If I thought of the hyenas at all it was to tell myself that ignoring them proved my love for the woman.

The woman and I didn’t wait to get back to the States to get married—we did the deed that summer in Addis. She was a very good looking woman, tall and slender; people mentioned her resemblance to Virginia Woolf. As it turned out, we weren’t suited for each other, but we didn’t know that then, and behaved as if we would be together all our lives. After our stint teaching in Ethiopia, we enrolled in an English graduate program in the Midwest, and both earned advanced degrees. We had a baby and I wasn’t drafted into the Army to fight in the war that was raging at that time in Asia. Then I got a job teaching at a small private college and we settled down to live a normal life. Things went downhill after that, as they often do.

In the years since I fed the hyenas on that return trip to Ethiopia, I have imagined that the Hyena Man invited me into his shack to meet his family. In truth, he did no such thing, but I have still imagined it. It is early evening. I peer in at the door. A naked toddler with flies clustered around her eyes crawls on a dirt floor. In one corner a woman in a tattered shawl is tending a brazier. The chairs and small beds are made of the narrow trunks of young eucalyptus trees and bound together with leather straps. On the radio a man is speaking very fast in Amharic. In a distant room a baby is bawling. The air is thick with the stink of the pail of offal set beside the door—the offal is for the tourists to give to the hyenas. In the midst of this the Hyena Man sits crosslegged, he is sharpening the sticks that the tourists will use to feed the hyenas.

He rises and waves me in. I meet his wife and children—four of them, none of them higher than my knee. The wife disappears and comes back a minute later carrying a tray with a bottle of the local beer and glasses for her husband and me. I accept the beer and drink heartily. The Hyena Man speaks just enough English and I speak just enough Amharic that we can discuss the terrible drought and the famine it has caused. But it becomes clear as we struggle to converse that he has something else on his mind, and gradually the pressure of what he has not yet said becomes so heavy that we fall silent. At that point, he motions that I should follow him into an even darker adjoining room, and I do. Gradually, my eyes adjust. In the corner a kind of playpen gradually becomes visible. Inside it, an ancient wizened little beast cowers. The thing can barely stand, and makes a pitiful noise when the Hyena Man stoops and picks it up and brings it to me, cradling it in his arms as if it were a baby.

But it’s not a baby, it’s a hyena—grown bald with age, its shrunken head little more than a lolling tongue, yellowed teeth and eyes the size of fingernail parings.

“Here,” the Hyena Man says in his suddenly improved English. “Take him!”

I hesitate, but he thrusts the ancient beast into my arms.

I look into its tiny, slitted eyes, and then at the Hyena Man.

“He’s been waiting for you all these years,” he says.

I ask him what he means.

“The road to the village,” he says. “Remember?”

Perhaps it’s the shudder that runs through my body that triggers the attack. Suddenly the beast’s jaws are on my throat, crushing my windpipe. My sight blurs as I fall to the floor.

“Fool,” the Hyena Man says. “Fool.”