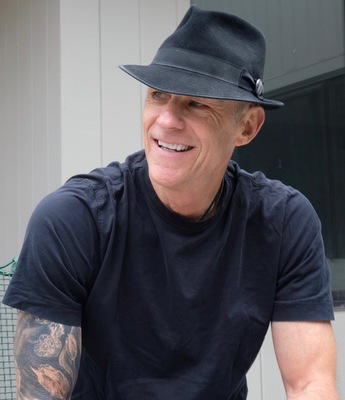

Deac Etherington

Fiction

Deac Etherington was a finalist for the 2017 Arcturus Award for Fiction, Chicago Review of Books; finalist in the 2018 and 2019 fiction contest at the San Francisco Writer’s Conference; winner of the 2018 Flash Fiction Contest for Light and Dark Magazine; winner of the 2018 Fiction Contest for Prime Number Magazine; and winner of the 2019 Hemingway Shorts Contest sponsored by the Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park. His work has also appeared in Projected Letters Magazine, and he has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. He holds degrees from Connecticut College and Wesleyan University, is a former English teacher and headmaster, and an SSI Divemaster. He lives in Southern Arizona where you can drive all the way to the Sea of Cortez when you want to change the view. He is currently at work on a novel. Find him on Facebook.

Asylum

At midnight she reached the migrant shelter in Nogales, Sonora. A heavy woman greeted her at the door beneath a mothy light. Her kind eyes set deep in a face shadowed by disappointment.

“Welcome to Albergue Para Migrantes. You have missed dinner.”

The girl went inside. She had long black hair and green eyes and a gap between her front teeth. Her mother used to say she would have been pretty except for that. In the big room filled with bunks where the women slept, she found a little girl’s doll wedged between her mattress and the bedframe. It had crazy pink hair and a grimacing mouth and black eyes in an alabaster face. She slipped it in her book bag. Felt like a rescue. She listened to night-time breathing noises of eight other women in beds all around her, the air like fusty laundry, and she supposed she felt safe.

The next day she crawled into America.

A boy from the shelter showed her how. He was confident the way boys are who have learned to fend for themselves in the colonia and are too young not to be fearless. He was only at the shelter for a few free meals but they let him stay anyway. After breakfast he guided her through the city streets to a section of the border wall that he knew about. That everyone knew about. He dug up a car jack hidden nearby and positioned it to raise one of the steel plates so she could squirm underneath. She did this quickly. When she looked back he waved at her through the gap in the wall and vanished. The border in that area traversed a hillside separating Mexican homes from a US commercial district. The whole area in full view of the world, but no one was looking. Like a lot of places on the border. The girl’s name was Rosa. She was seventeen.

~

She started walking. Blending in was easy. She wore jeans, a black hoodie, sneakers. She carried a blue book bag with a rubber daisy attached to the zipper that flopped around as she walked. There were also buttons from her favorite bands. The Black Belles. Go-Betty-Go. In Hermosillo, before everything changed, she and her friends would drive down to San Carlos to the boat they called Barco de Fiesta because it never actually went anywhere. Just stayed at the marina for partying. They had speakers on the deck and drank tequila and dared the boys to jump into the harbor and come up the other side of the boat. They were all supposed to be going to the Universidad de Sonora in two years. But that was the spring her father vanished in Sinaloa. And her uncle came.

Her uncle had an oily face and strands of hair shellacked across the top of his head. He said that because of what happened with her father they had to go north without delay. That it had fallen upon him to take care of them now. He took Rosa and her mother to the crowded hillsides outside of Nogales, Sonora. In Colonia Colosio there were no paved roads or running water. Their house was made from corrugated metal, sheets of plastic, scrap wood and fence wire. It’s where her mother disappeared inside herself and stopped talking. At first Rosa didn’t know what her uncle’s intention for them was. Or why her mother went away.

Then she did.

~

A few miles down the road beyond the commercial district a bright orange car slowed alongside her. Music loud. Someone’s feet sticking out the window. One sneaker off. Pink socks. The car was full of girls and they were laughing. At her, probably. Rosa smiled and waved a little and the girls laughed harder. Then one of them leaned out the window and shot water at her head from a plastic bottle. The car accelerated with a blast of exhaust. Rosa wiped her face with her sleeve. And the road got quiet again.

It was dark when she reached the gas station. She was relieved. Now there was a bathroom and a mini-mart. People coming and going. Things bright in the parking lot lights in an area otherwise surrounded by desert. Rosa settled against the wall. No one noticing her, except for this one couple who came up to her and wanted to know if she had found Jesus. Rosa, who spoke perfect English, asked how long he’d been missing. The couple smiled politely and handed her a pamphlet with a picture of a sunrise. Then they walked away. What she really wanted was something from the Taco Bell. Or the mini-mart. She put her head back against the wall and closed her eyes. She had no idea how tired she was until she did that.

~

“Hey. That’s you, right?” Rosa looked up. A girl was back-lit in the glow of the parking lot lights. She was slender with piled-up black hair and bangs straight across her forehead. She was wearing yoga pants and a biker jacket over a white t-shirt and holding a bag from Taco Bell. “That was you. Out on the road before. Am I right?”

“I guess. Why?”

“You live around here or something?”

“Maybe.”

“Well what does that even mean?”

Rosa squinted at her.

“That I’m keeping my options open.”

The girl smiled.

“Options. Got it.”

Rosa smiled back. But just a little.

“Sorry we threw water at you,” she said. “That was mean.”

“It’s okay.”

“No, I feel bad. Sometimes my besties are such jerks.”

Rosa was looking at the bag from Taco Bell.

“You know what?” said the girl. “I don’t even know why I ordered this. I need to lose five pounds, like, yesterday. My boyfriend already thinks I’m fat. Boy, is he in for a surprise. Tonight’s our three-month anniversary, which is kind of a big deal. Especially now. But I’m pretty sure he forgot. Guys always forget. Anyway, here. You take it.”

“Really?”

“You’ll be doing me a favor.”

She put the bag in Rosa’s lap.

“Thanks.”

The girl stood there. Hesitating.

“Okay,” she said. “Here’s the thing. If you’re really, like, a runaway or something, then I’m going to feel even worse than I did before. There’s this sick party in the desert tonight. If you have no place else to go you should come with us. It’s better than here and you might even find a place to crash. Besides, it’ll be fun. I’m Angela.”

“I’m Rosa.”

“Come on. Let’s go.”

Rosa got up and they stepped into the parking lot.

“I like The Black Belles too, by the way,” said Angela, glancing at the blue book bag. “People think I look like Olivia Jean because of my hair and Goth-eyes.”

When they got to the car the other girls made a space in the back seat. This is Rosa and she’s coming with us to Lost Arroyo so whatever. Okay? Then they all started talking at once, but not to Rosa, and the music in the car was loud, and no one seemed to really care that she was there. But they didn’t seem to mind, either. They turned north onto I-19 and accelerated. Rosa gazed out the window, things passing fast, like being lurched forward on a carnival ride.

And the border fell farther behind.

~

The Lost Arroyo was a wash at the end of a ranch road where they had set up a keg near an old cattle-tank. A big fire exploded sparks beneath stars in an ancient darkness. Rosa sat off by herself just beyond the glow. She was a stranger here, yet she wasn’t. This was a scene she understood. These were her peers. They might have all just come from the Barco de Fiesta. They would have all shared the same dreams in Hermosillo. And the gap in the border wall would have looked the same to them, too. No matter where they stood.

Sometime after midnight she saw Angela and her boyfriend near the fire. Silhouettes rigid against the moving light. Their voices like verbal shards. The others avoided them the way you slip past that shouting couple in the parking lot at Walmart when the boxed baby-crib won’t fit in the car. Then Angela slapped the boy in the face. He spat in the desert and walked off in the direction of his jeep.

The Aquadolls came on.

“Turn that up,” said Angela.

She went over to the keg.

Rosa bowed her head so that her face was tented in her dark hair and the fire showed through it in glowing pulses. A way she sometimes pretended to disappear in their squatter house in Nogales. Until pretending wasn’t enough. That was after her uncle took her out to the abandoned van where another man waited. Even though the sun was down, Rosa remembered how hot the van was inside. She remembered the smell of oil and metal and how the old packing blankets were piled in the back like a mattress. And she understood the silent place where her mother had gone. That last night, while her uncle slept, she broke both his knees with a hammer.

~

Angela walked over. Leather jacket creaking. Feet dragging in the sand.

“So much for happily ever after,” she said.

“What happened?” said Rosa.

“I got pregnant. Then dumped. Lucky me.”

She sat down next to Rosa. Beyond the fire bodies moved through the mesquite trees like shape-shifting spirits. Glass broke. And a girl’s shrieking laughter died in the dark.

“I was going to college,” she said. “That’s pretty funny, now.”

Rosa looked at the fire. Nodded slightly.

“Tell you something else that’s funny,” said Angela. “My parents decided to kick me out of the house today. They don’t want me around my brother and sister right now. My corrupt moral compass or something. Well fine. I’m eighteen. I was leaving anyway. So I packed my big pink suitcase and put it in the trunk of my car and drove away while they both stood at the living room window like two dead people on a tintype. I told myself it wouldn’t matter. Because tonight was going to be the perfect time to tell my boyfriend everything. About the baby. About how I had to move in with him. I mean, it’s not like we never talked about that. But he just looked at me like a zombie and said this really wasn’t a convenient time for him right now. Convenient.” Angela’s eyes got shiny and strands of hair trembled against the side of her face. “Now I don’t know what I’m going to do. I sort of have some friends in Tucson. But I really don’t know what happens to me next.”

Rosa slid her hand beneath Angela’s.

Felt the other girl’s fingers tighten.

~

The last of the cars rumbled away. Rosa stood at the edge of the wash. She sensed the desert stirring after the long night. A breeze curled through the creosote bushes, bringing the smell of desert grasses, and there was the faraway burst of screams from coyotes that stopped as soon as it started. Left you wondering.

“I guess it’s just you and me now,” said Angela, walking up from her car. “I found some jeans and a t-shirt. I think we’re about the same size. The shirt says I-heart Joey Ramone. But you get used to it. Here.”

“You sure?”

“It’s no problem. I basically dumped my closet in that suitcase.”

Rosa slipped out of her own clothes. Pulled on Angela’s jeans and t-shirt.

“How do I look?”

“Reborn.”

She opened her blue book bag. Took out the orphan doll from the migrant shelter to make room on the bottom for her old clothes.

“Hey. What’s that?” said Angela.

“My día de la niña muerta.”

“No,” she said. “That.”

She turned Rosa’s arm so the reddish slash marks showed.

It pulled her back to the kitchen table in the squatter house. Her uncle asleep in the other room. Her mother leaning against the wall in the kitchen with blankets wrapped around her shoulders. Her mother was staring at something in the air between them as Rosa slid the razor against her skin. Gently. One cut after another. She took her time. Which was when Rosa knew she could do whatever she chose with that razor blade because her mother was gone forever and she was alone.

“This was when I decided about the hammer,” she said.

“Hammer?”

Rosa glanced down at the doll with crazy hair and black eyes.

“It’s for when God misplaces your life. And you want it back.”

Angela put her hands on her hips. Shifted her weight.

“Okay,” she said. “So maybe you could show me that, too.”

“Show you?”

“About the hammer.”

Rosa glanced away for a moment. And she wondered now if running away meant that your first steps had to come through a place like this. A desert. Because this emptiness was also an invitation. Like any blank canvas you did not know where the first bits of color might appear. Only that they would.

“Well,” said Rosa. “I guess we’re already sharing a suitcase.”

Angela smiled a little.

“I guess that’s true.”

“So. How far is Tucson?”

And the sky began to pale.

“ There’s a lot of discussion about the southwest border right now. Against this backdrop, I was interested in a more nuanced sense of what ‘asylum’ can mean. This story blurs the lines that separate us and sharpens the focus on our shared humanity. ”