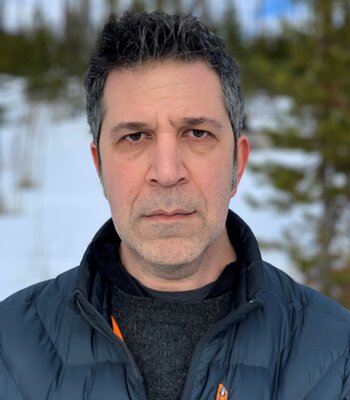

Scott Nadelson

Fiction

Scott Nadelson is the author of seven books, most recently the story collection One of Us. His work has recently appeared in Ploughshares, New England Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, and Best American Short Stories 2020, and he teaches at Willamette University and in the Rainier Writing Workshop MFA Program at Pacific Lutheran University.

Among Thorns

The dizzy spells likely started soon after his army service ended. But Ilan spent most of that year drunk, so at first they were hard to distinguish from the regular spins he experienced after leaving a bar or waking naked in a strange man’s bed, first in Cyprus, then in Turkey, and finally in Spain. He often forgot to eat, and many mornings he threw up whatever he’d gotten down the night before. By the time he made it home to Haifa, a few weeks past his twenty-second birthday, he’d lost nearly twenty pounds. His ribs showed through his shirts. Veins appeared close to the surface of his skin, forking down his forearms, over his temples, across his bony chest.

His mother tried to stuff him back to health, but even after he’d begun to fill out again, color returning to his face, the dizziness remained. He quit drinking, mostly—except for an occasional binge with friends in his university classes—and still he’d experience the strange tumbling sensation, not sideways like a drunken spin, but more of a forward roll, as if someone had pushed him hard from behind. It happened two or three times a week, always when he wasn’t expecting it: during a biology lecture; while drinking coffee with a new boyfriend, whom he hadn’t told how many men he’d slept with the previous year; in the shower, where he had to lean against the tiles to keep from falling.

He didn’t say anything to his parents, and if they noticed something was wrong, they didn’t let on. His mother was just relieved to see him eating, and his father, worried about finances and the retirement he’d been counting on since the day he’d started working, spent most of their time together offering advice about careers. “Do something you love,” he said, “or else you’ll just wish your life away.” The boyfriend was too smitten and sex-blind to recognize anything beyond his own pleasure.

Ilan avoided their family doctor and instead found one at the university health clinic. While waiting in the examination room, he stared down the slope of Mount Carmel onto the city where he’d spent his first eighteen years, and beyond it to the sea he’d crossed the week after he’d ceased being a soldier. He imagined himself on his way back to Cyprus, back to the obliterating bliss of those first months abroad. But then he felt another roll coming on and lowered himself carefully to the edge of the exam table. Along the paths outside, fit young people hurried to classes without stumbling or falling. What had happened to him? When he’d reported for service, his body had been perfect. He’d been approved for a combat unit after his first physical. After two years, he’d come out more muscled and more tan. His only visible wound was a bad nick he gave himself while shaving with a straight razor he used only to show off to others in his squad.

The doctor was an American in his early thirties but already balding and paunchy, the type who’d been enamored of Israel since he was a boy but who’d waited to make Aliyah until he was too old for conscription. “Where did you serve?” he asked, in stilted Hebrew, as he looked over the numbers the nurse had written down, temperature and heart rate and blood pressure. What business was it of his? But Ilan answered anyway, “First Ofrit. Then Hebron.”

The doctor didn’t ask any more. Instead, he talked about diet and exercise, said he thought it was probably low blood sugar, that the nurse would take a sample and send it off to the lab. “You need to get on top of it early,” he said, in English now. “Diabetes isn’t something you want to live with for sixty years.”

Sixty years sounded impossibly long, too long for anyone, but Ilan thanked the doctor and watched his blood filling tiny vials the nurse held at the end of a rubber tube. When the results came back negative—for hypoglycemia, as well as STDs—and the dizzy spells persisted, the doctor suggested more tests. He tried not to show any concern, but Ilan could see it in his small, watery eyes, the set of his girlish lips. He’d been smart to avoid army service, Ilan thought. The other boys would have pinched his pudgy belly blue, wrapped him in blankets and abandoned him in the Negev in the middle of the night. Keeping his head down in the States until now was best for everyone.

“What sort of tests?” Ilan asked.

~

A week later, he rode a bus to the port, alone, and from there walked to Rambam Hospital. It was a morning he didn’t have class, and he’d told his parents he was going to interview for a part-time job at a café. “Give it two days,” his father had said, “and if you don’t enjoy it, quit on the spot.” To the boyfriend, whose flat he usually visited for lunch and a fuck, he said he needed to put in some extra time in the lab, had to finish a report. The boyfriend was petulant on the phone, a whining child, and Ilan decided as he passed through the front doors of the imaging center, the smell of the sea strong until overtaken by disinfectant, that he was finished with this one, he’d sleep with someone new the first chance he got, whatever the tests revealed.

The doctor had decided on a PET scan rather than an MRI, and the acronym made him picture a small dog, a friendly one who’d follow him wherever he went. “My little PET,” he joked with the nurse who gave him a paper gown to wear before injecting him with a radioactive liquid that would highlight any unusual activity in his organs. The technician was tall and clownish in scrubs, with long eyelashes and a high smooth forehead, and Ilan tried to flirt with him as he readied the machine. “I bet this is how you get the girls,” he said, the paper gown hardly reaching the top of his thighs. “Or maybe boys? Once you find out they have only six months to live, then you pounce.”

The technician laughed, but briefly, maybe coldly, and Ilan wondered if he wore a kippah underneath the surgical cap. He was sick of this uptight country full of fanatics. If he got better, he’d leave again, and this time he’d stay away for good. But as soon as he thought so, he felt a pang for the boyfriend’s firm body and soft tongue, for the hour he could lose himself in friction and sweat and panting breath. By then he was on his own in the room, and the PET was buzzing, more like a giant locust than a little dog. The test lasted longer than he expected, longer than he cared for, but he’d gotten used to waiting during his two years in the army, waiting in barracks, waiting at guard stations, waiting in position above a street in Hebron, where nothing happened for hours at a time.

And when it was over, there was only more waiting. The technician betrayed nothing on his face as he turned off the machine, gave no sign that Ilan should worry or relax, though he did let his eyes drift across Ilan’s thighs as he sat up, the paper gown hitching toward his waist. Ilan put both hands over his crotch. “We’ll get the results to your doctor this afternoon,” the technician said, his back turned, body shapeless beneath sagging scrubs.

~

The next day he stopped at the boyfriend’s flat at lunchtime, stripped him down before he’d even kissed him, and then lay in his arms longer than he meant to, skipping a lecture and a lab. The boyfriend was asleep when he finally got up, sitting on the edge of the bed and feeling that forward roll. Even when he put his head between his knees, it kept going, as if he were a gymnast whirling around a greased horizontal bar.

He found a bottle of vodka in the boyfriend’s kitchen, mixed a tumbler with grapefruit juice before heading to his last class of the day. His professor lectured about the interaction of viruses in cells, the way human DNA had been altered by diseases that had disappeared from the planet thousands of years ago. Ilan pictured the radioactive liquid moving through his body, an electric green streak passing from brain to heart to lungs to liver to kidneys, and finally streaming out his cock into the toilet. He wanted to imagine it flushing out whatever made him tumble so insistently, giving him back control over his senses.

But even after he drank three liters of water and pissed himself dry, there it was, the nudge on the spine he couldn’t feel, the resulting force he couldn’t resist.

~

He waited two full weeks after the test before going back to the American doctor, canceling one appointment at the last minute and rescheduling twice. By then he’d broken up with the boyfriend and taken him back, their sex fiercer and more distracting for a few days before returning to routine. He was a lovely boy with strong shoulders and a hairy chest, who liked to talk about history and the World Cup, and that Ilan felt nothing for him but lust he blamed on the dizziness or its source, whatever was emptying him out from the inside.

This time as soon as the nurse finished taking his stats, he lay down on the exam table, the sanitary paper crinkling beneath him, and closed his eyes. He kept them that way as the door opened and closed, rubber soles squeaking toward him, then the tap of a pen on a clipboard, the smell of strong medicinal soap. Before the doctor could speak, Ilan said in English, “It’s psychological, I know. It’s obvious. Probably has been to you all along. I should go to a therapist.”

He didn’t give the doctor a chance to respond. Instead, he kept talking, slowly but without pause, telling the American what he suspected he’d been curious about since Ilan’s first visit: the tedious months in Hebron, maintaining position for six hours a day on the roof of a building across the street from the settler compound they were meant to protect, even though most of the boys in his unit hated those settlers who caused everyone so much trouble, far more than the Arab residents who’d spit in the street after the soldiers passed. He wasn’t political, he told the doctor. Yes, his grandparents had been refugees, part of the great pioneer generation, but that was all so long ago, how could it mean anything to him now? He just wanted to do his duty and then live his life, go to school, earn a living, maybe have a family.

That was what he wanted for the residents of Hebron, too, who looked at him with hatred and terror when he patrolled the streets. Up on the rooftop he could pretend they were the people he was protecting, and not those Kahanists with their thick beards and smug piety and scornful way of speaking to the soldiers who kept them alive, especially those without head covering, or worse, the female military police in trousers and hair too short to pull back into a bun. And if they knew what Ilan was, how he spent his free nights, and with whom? They would have despised him, cursed him, cast him out. He was no Jew to them, but they benefited from his silhouette against the sky above their compound, rifle resting across his knee. It gave them the right to harass residents returning from the casbah, or so they must have believed. He was clearly visible when several teenage boys surrounded a pair of women, one carrying an infant, and knocked their sacks of vegetables to the ground. The women ran away, and the boys shouted after them, tossed stones at their backs, and not once did they glance up to see what Ilan thought.

It made him so angry, knowing he gave them cover, and knowing, too, that they took his presence for granted. One of the stones hit the woman carrying the infant, right between the shoulder blades. She stumbled, recovered, kept running. Ilan raised his scope only so he could get a better look at the boys, recognize their faces in order to confront them next time he spotted them while on patrol, or else report them to the police who handled settler violence. He had his safety on; his hand was nowhere near the trigger. But he stared at those boys’ faces, with their first wisps of beard, their pimpled noses, and felt all his weariness and boredom and disdain rushing through the scope. Eleven months of guarding these boys with whom he shared nothing but a common ancestry in a Europe he’d never visited. He could have shot them as easily as any of the terrorists he was meant to look out for. The desire to punish them rose up so strongly in him that he experienced it as a sudden thirst, so overwhelming he found his tongue stuck to the roof of his mouth, his nostrils itchy, parched air scorching his throat, and maybe a part of him believed he really was getting ready to shoot them, or was shooting them already, because when he heard the footsteps of the soldier coming to relieve him, the crunch of ancient stones beneath heavy boots, he started, lost his balance, nearly toppled off the roof into the street.

And of course that’s what he was still feeling, he told the doctor, his eyes remaining closed. It was obvious, wasn’t it? Just the horror of imagining what he was capable of, picturing himself pulling the trigger and watching as each boy flopped on hard ground. And no matter how much he drank or how many men he slept with, he wouldn’t shake the dizziness, because it was just in his head, right? Because it would be too absurd a coincidence, too perfect an irony, if there were really something wrong with him, if soon after he’d felt himself tumbling from the dusty building in Hebron, a mutation in his cells made him relive that tumbling over and over again. That sounded too much like divine retribution, but he didn’t believe in divinity, and anyway, wouldn’t such reprisal seem too severe even for someone who did?

“I’ll go to the counseling clinic as soon as I leave here,” he said. “Maybe you can refer me to someone good.”

And only then did he open his lids and take in the soft feminine features of the American doctor, the shiny bald head and little eyes blinking behind narrow lenses, plump hands raising the clipboard with the results of his test, pale lips parting to tell him what they said.

“ For a long time I tried to write about a young Israeli I met years ago in Spain. He’d just finished his military service and was trying to drink away all memory of his time in the army. The story finally came together when I imagined what happened to him when he finally made it home. Somewhere along the way, it also became an attempt to revise 'The Jew Among Thorns,’ the most anti-Semitic of the Grimm brothers’ collected fairy tales. ”