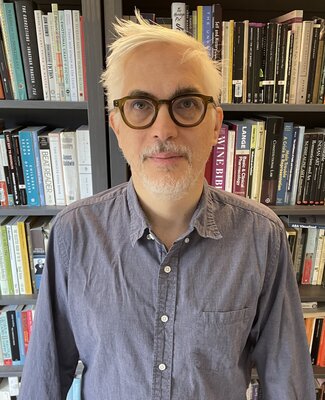

Jared Hanson

Fiction

Jared Hanson received his MFA from Columbia University and lives in New York City. His fiction has been published in the Gettysburg Review and Pembroke Magazine.

Wild Edibles

Lucian learned about his grandmother’s death from a quit-claim deed he received in the mail. He hadn’t seen the house in twenty years and he couldn’t remember when he had last spoken to his grandmother. The house wasn’t much, but it was tucked away in the woods on the edge of the hilly town of New Sweden, where he had grown up, and its permanent location there and her steady occupation of it had been the only notes of stability in his early life. He had lost his job at the tire shop and Nilsa had disappeared again, for almost six weeks this time, so Lucian took their daughter Mildred up to Pennsylvania to look at the house. He already owed the landlord $1200 in back rent; they could stay if it felt right, or go back the next day. It wouldn’t matter. His daughter had never had much and he, in the twenty-three years since he left New Sweden, hadn’t accumulated anything of any value.

She had died in the front yard. Fallen down on the driveway while walking to the mailbox, still quite alive on the gravel but unable to get back up, she had struggled from Saturday afternoon to noon on Monday, eventually succumbing to a heart attack, the coroner guessed, half an hour before the mailman came around again. Her neck was wet, the mailman told Lucian, where he had tried to take her pulse. At first he had thought it was dew but later realized it had been sweat.

There was nothing to see. The body had been donated to a medical school in Philadelphia, and Lucian hadn’t been a person anyone, including the lawyer who sent the deed, had thought to call. If someone had been called, they hadn’t organized any service.

“I never seen anybody else out here,” the mailman said.

Most of the food in the fridge had dried up or expired, and Lucian took Mildred to Acme in the morning to buy milk and cereal and three oranges. In the fruit section, he assigned her the task of unraveling one thin, green-tinted produce bag. Beside them a young woman waited as Mildred struggled to tear the bag off at the perforation.

“Do you want to get one for me?” the woman asked, with a quick rise on the me. Lucian immediately felt regret at having returned to this town, for introducing his daughter to this place with its impatient young women dressed like kindergarten teachers. It was May; if they stayed he would have to enroll Mildred in school.

It didn’t help that he knew the cashier in the express line, never a friend but a classmate for ten years, someone to be maneuvered around in the doorways of teenage parties or knocked against during pickup games at recess. He didn’t ask Lucian how he’d been or where he’d gone, acknowledging him only with a disinterested ‘Hey,’ as he passed the bag of groceries. They were everywhere. Waiting at a trolley crossing, he read the placard on a converted house, now an allergist’s office; the doctor was the son of a foster care family that had taken Lucian in for four months while his mom washed out. From a billboard hanging above the Sunoco station, the face of a girl he had unpleasantly moped about in tenth grade beamed down on him, now apparently the most trusted real estate agent in the county. These were the visible ones. Every body lurching down the sidewalk, every arm hanging out an open car window seemed recognizable: an unrequited teenage love, an unforgiven casualty from an afternoon skirmish, a classmate’s suspicious parent, caseworkers, teachers; Lucian saw his father’s second AA sponsor pushing a cart full of orchids down the cement ramp at the entrance of a new Trader Joe’s. There was a garage half a mile down the road from his grandmother’s house; Lucian had considered asking around there for work until he noticed that the sign had changed and now bore the name of a notorious middle school bully two years ahead of him. Lucian had been suspended in sixth grade for biting him in the forearm; he remembered the taste of the blood and the pleasure he took in it.

The first thing he did back at the house was to call and cancel the cable service and landline. After he hung up, he realized they had still been on her name; he should have waited until they stopped service for nonpayment and then let them try to collect on a dead woman. He stopped the mail but left the water and electricity alone. They walked around the yard. Young tomato vines spread out over a few rows of leaf lettuce in the small kitchen garden and behind the garden a few dozen yards of forest led down to a stream. There was a shed and behind the shed a pile of ashes and an empty compost bin.

“What’s this, Daddy?” Mildred presented him with a brown blob she picked up out of the periphery of the ash pile. It was a fleshy collection of pits with a stalk.

“I don’t know, babe,” he said. “Maybe a mushroom.” He dropped it into the high grass and it split; from the hollow center a small slug waved at them with wet antennae.

She had collected twelve by the time he dug the lawnmower out from the shed.

“Don’t touch those,” he told her after a few yanks on the pull cord.

“Why not?” she said.

“Could be poison.” He gave three short tugs and the cord tore on the fourth. “Fuck,” he said. “Fuck, fuck, fuck.” He shoved the mower into the shed, clattering a stack of terracotta pots. When the door didn’t close again, he slammed it against the handle of the mower, trying to push the mower in with each slam. Eventually the top hinge on the door gave out and it was impossible to swing the door open and shut. Lucian squatted and lifted the mower from the bottom, rolling it up over the pots, exposing the blade and the clumps of dry brown grass underneath. It hurt his back to do this. He hadn’t meant to yell, but the pain and the fact that he still couldn’t close the shed door made him curse Nilsa as loud as he could and, after berating her mother with as many expletives as he knew, he couldn’t blame Mildred for running around the other side of the house, crying by the pile of old trash bags where, he guessed, his grandmother had dumped her garbage when she could no longer walk it out to the road.

The collection of mushrooms lay like a pile of small brains in her lap. She had named them. “This one’s Steve, this is Millicent, here’s Tuba and Lefty . . .” With each recitation, he got calmer. To make it up to her, he scrolled through a few screens of images on his phone. They were in fact mushrooms. “They’re called more-L’s. Or morals. Something like that.”

“So they’re not poison?”

“Apparently they are quite delicious.”

He sautéed them for lunch, flicking the slugs out the jalousie window over the kitchen sink, and the pride she felt over the meal made him feel like he had done something right. They emptied the fridge that evening, filling small plastic grocery bags and hurling them onto the top of the pile at the side of the house. In the morning, she picked the front yard free of yellow dandelion flowers and he made fritters out of them with a box of pancake mix. The old woman was well-stocked with dry goods in the pantry, and he was relieved that he wouldn’t need to go back into town. For lunch he made a salad of some of the dandelion greens; it was easy for him to recognize them now after the morning search and he showed Mildred the tubes bleeding milky sap and compared the leaves with other unknown weeds growing in the yard. She enjoyed collecting the leaves but balked at the bitter salad. He melted some sugar in water for syrup and served her the rest of the pancakes.

Without TV, Mildred fell asleep early, and in the dark Lucian scrolled through message boards on wild edibles, looking for a substitute for maple syrup so he could avoid the grocery store the next day. She woke at dawn and they walked along the margin of the forest, trimming the young needles off the white pine saplings and boiling them down in simple syrup. It tasted nothing like maple, but Mildred stood on a stepladder, watching over the pot jealously, and emptied her plate without a word.

When they ran out of dandelion leaves, he taught Mildred to identify chickweed instead. With a few weeks of bitter salad for lunch, he had begun to lose weight. The chickweed faded as summer came on, and he replaced it with wood sorrel and purslane, which grew in the packed dirt close to the house or the road, mixing it with the outer leaves of the leaf lettuce.

When the pancake mix ran out, he learned to make bread from YouTube, building a sourdough starter over a week. Mildred loved kneading the dough and shaping the loaves; they worked their way through boules and batards, pain de mie and flatbreads and even pizza, topped with a pesto of wild onions and roasted fiddleheads. When his grandmother’s stash of Maxwell House ran out, he wandered deeper into the underbrush of the thin forest, clipping the buds and small twigs off the low, straggly trees of spicebush and boiling it in water. He had been sleeping better and didn’t miss the caffeine.

After a few months, a PECO and then an AQUA truck parked in the driveway, the drivers pounding on the door and leaving notices over the silhouettes of their fists in the yellow pollen dust on the gray semi-gloss paint. Lucian and Mildred ducked under the dining room table, competing for who could be quietest as the strangers circled the house. The days were long and, without power, they began to rise and fall with the sun. He had never been so well rested, but he still found himself waking in the middle of the night, the little girl blinking in the darkness beside him, asking him about the future and all the wonderful things that would happen to her.

Without water they made three trips to the stream a day, crossing to the other bank at dawn where he had dug trenches for them to use as a latrine and washing in the ankle-deep flow afterwards—when they ran out of bar soap, he washed her hair with Ajax, filling a garden watering can and sprinkling the greenish water over her long hair and peeling skin. They didn’t drink the water like that. He would let the larger bits settle out in the buckets before pouring the water over a filter he made by piling a thick layer of traction sand he found in the garage over several layers of his grandmother’s old clothes, and boiling what came through. Four times over the summer a storm appeared in sudden violence and the rain came down forcefully, and the two of them would run out on the deck and undress in the noise, shouting, wiping the water over and off their sinewy bodies.

Without gas, he had first used up the cylinder in the outdoor grill and then began to make fires. The firewood she had stacked for winter didn’t fit under the grill, and it was too hot in the house to use the fireplace. He dug a pit in the backyard, lining it with cinder blocks to support her thin aluminum pans. He kept the fire going all day: to boil the water, bake the bread and cook dinner; the nights now and then could even be a little cool and it felt somehow primal to sit with Mildred in the early evening and watch the stars come out.

He tried to be judicious with the firewood. They began to collect sticks and small logs from the woods. He found an axe in the garage and chopped down every small tree that he could not find another use for and laid them out to cure, gradually working on three larger trees that had fallen over the stream, salvaging a large pile of crumbling dry wood. He looked inside the house too: paper, old books and magazines, rags, cardboard boxes, anything that would burn.

Summer brought milkweed, stinging nettle, shaggy manes, blewits, and later sulfur shelf, which tasted so much like chicken breasts that Mildred cried. Everywhere he looked there was lamb’s quarter—they couldn’t pick it all—and in the low, wet spots he dug up the long taproots underneath the burdock leaves. There were enough blackberries to make several crumbles with the last of the sugar; the caramel odor of it burning in the nonstick pan over the firepit mixed with the blooming scents of honeysuckle and Queen Anne’s lace and the sound of the cicadas, and he thought for a moment that he had founded a ramshackle paradise.

Lucian did make one more trip to the grocery store. He had only been turning his phone on to identify plants, powering off quickly, paying the bill with three credit cards he found in the kitchen coupon drawer and letting the motor run in his car just long enough to fully charge it, something he had turned into a treat for Mildred, cranking the air conditioning on cloudless humid afternoons and directing the vents over her forehead so her hair rippled behind her. After the fuel light came on, he filled it at midnight at a Wawa, treating himself to a caramel cream smoothie. Walking through the rows of potato chips and prepackaged baked goods up to the racks of candy at the register, he felt a distension in his chest, a hunger, and an urge to make himself throw up. The sweetness and coldness of the smoothie created a drawing sensation behind his forehead; he was aware, for what felt like the first time, of his own pulse as it accelerated out from his heart. He considered buying an ice cream bar for Mildred, waking her in the darkness where he had left her asleep on the sofa cushions lined up over the carpet in the living room, but he remembered how little money he had left, calculating how many more tanks of gas he might need to buy, or what sorts of emergencies he might still encounter. He had begun to worry about nutrition, a growing child’s need for protein, for calcium, essential fatty acids, trace minerals. At the 24-hour Giant, the aisles were empty except for several men his age stocking shelves. He didn’t recognize any of them and collected only a few bags of flour, some eggs for a treat, and bananas, embarrassed by each loud beep that echoed through the store as he waved the five items over the scanner at the self-checkout.

Near the entrance, an old man struggled to withdraw his left arm from the deflating cuff at the automatic blood pressure booth by the closed pharmacy counter. An old woman, supporting herself with a cane, held his arm as he rose to sit in a motorized shopping cart. Lucian stopped, catching the man’s elbow as he stumbled. The old woman recoiled for a moment, her eyes sweeping over him, before swatting his hand away with her cane and brandishing the rubber butt of it at his throat.

“We’re quite all right, thank you,” she hissed.

Since they had lost water, Lucian never went in the bathroom and didn’t miss the mirror there. His beard had filled in now and he knew he might look sloppy, but he hadn’t been prepared for this level of disgust.

“Is that Lucian?” the woman said.

He remembered her slowly: a member of his grandmother’s singing group, she had managed the food bank in Lower Providence. She had seemed so old even then, though he remembered her teenage daughter and how much he had admired her relentless cigarette smoking. She asked him how he was now, if he was living somewhere, when had he last seen his mother, his father, his sister, if he needed anything, if she could buy him something to eat. He told her about his grandmother, her passing away.

“She was such a nice lady.”

“I honestly can’t remember,” he told her.

“It was just a scare,” the old man said. “Thought we’d come check it out.” He shook Lucian’s hand and rolled into the bakery section, wheeling past the dark cake displays and empty bagel bins. Lucian took the opportunity to jog away without saying goodbye.

He didn’t need to do this, he thought. He could avoid it, he knew. He could replace the wheat flour with acorn mash; he would fill old socks with acorns and leave them in the stream to leach out the astringency. There were walnut trees on the far side of the creek; he had seen the black hulls of last year’s crop rolling under the ferns. He had, on a few occasions, chanced upon a low nest with small eggs; if he learned more about birds, his luck would improve. And it was time to think about small game. In the parking lot, on his phone, he learned to make snare traps from speaker wire, falling asleep under the weak lamplight by the cart return. He came home at dawn and Mildred was already naked at the creek, dunking her head in the water. She had caught two frogs for lunch and detained them in the watering can. In the afternoon, he caught a snake with his bare hands and instinctively bit the head off to stop it from writhing, but neither of them could stand the cloying smell of it. They were never desperate.

A week later, they were collecting grasshoppers from the high grass in the yard, filling a brown paper bag until they had enough to toast, when a Honda Civic pulled into the driveway. Lucian heard the turn of the gravel before seeing the headlight pull in behind his car. “Come on!” he whispered to Mildred, pulling her by the arm into the forest. They crouched in the leaves and he could hear the faint sound of knocking. Minutes later, there was the swishing of grass. Lying there, beneath the wild roses, facing his daughter, he brought his finger to his lips. She giggled.

“Hello?” came a woman’s voice.

Lucian put his hand over Mildred’s mouth and they waited. Above them, a woodpecker made irregular drumrolls. There was the sibilant, implosive sound of the fire being dowsed. He never heard the woman drive away, but on the front porch he found a vase of white lilies and a disposable cake pan of macaroni and cheese, still warm and tightly wrapped in aluminum foil.

By the second week of September, the firewood and stray forest wood was burnt and Lucian began to break down the back deck with the ax and a handsaw, peeling off the old paint where he could, and processing the furniture in the house down into sizes that would fit into the fireplace. The house was large and drafty, but he managed to accumulate a considerable pile of fuel. The dining table and chairs, dressers, the headboards of both beds, an armoire, the upstairs doors and trim and wainscoting, it lay in a splintering pile over the lumber where the deck had been.

Fall brought puffballs and ginkgo nuts. He had managed to catch one rabbit and a bird, and Mildred made a game of catching the mice that filtered in and out of the piles of blankets and old clothes that they slept under in front of the fireplace. He had been negligent, he realized, in storing up for winter. The fresh batch of acorns and walnuts would fall soon and there was a light abundance of fruit: wild rosehips, crab apples and black cherries, but his biggest hope was the small family of deer that drifted through the yard every few days now that they spent more time indoors. Just one could feed them for a long time. There were bags of road salt stacked in the garage; he could pack the meat in the salt to preserve it and then rinse it out in the stream as they needed it. He sharpened some of the longer wood shards into spears, experimenting with burning the ends to harden them or splitting the shaft and fastening a kitchen knife in the center. They were stupid beasts, unsheltered and susceptible, and he thought if he could hide on the periphery of the forest, if he could wait long enough, he could stab them once in the heart, wherever that was, and be done with it.

For three days, Mildred lay inside by the fireplace, sweating and complaining about pain in her stomach. In the daylight, outside, Lucian stood still, the spear steadied above him, but the deer never came. Instead, he would rely on ingenuity and, as she recovered, set about digging a deep trench under the brush, planting the sharpened sticks at the bottom, points up, and covering it with a loose latticework of twigs and leaves. They could wait inside, sipping sumac tea. If the soil didn’t freeze, if he didn’t need the sticks for burning, he thought he might dig more pits like this in the winter around the perimeter of what he understood to be his property, and he had made it a habit to carry one or two of the spears with him whenever he was outdoors. Someone would come one day, he knew—CYS, social workers, tax assessors—and he needed to be prepared to defend himself, to drive them away. It was a feasible strategy, he thought, for at least as long as his car would still start and they could make a quick escape. Out of the pits he dug large stones and began to stack them into a wall around the house.

The night of the first frost they celebrated with a tart from the last of the tomatoes over a crust of acorn mash mixed with the pounded inner bark of tulip poplars and seasoned with pepperweed. The leaves changed and, when they fell, Lucian and Mildred could see across the small valley over the creek. There were houses on the opposite hillside and they weren’t so far away. Over the bare trees, sounds carried farther and on weekends they could hear children playing, the elastic sounds of dribbling basketballs, and dueling leaf blowers. It was something Lucian didn’t remember about the place from his childhood. Late one Sunday morning, Mildred spotted two children in neon windbreakers on a distant patio and suggested bringing them a bowl of the green walnuts they had collected. It sounded so reasonable when she said it.

He was proud of her, for the spontaneous kindness and for this impulse to sociability that was so foreign to him, but also for the resourcefulness she had adopted: it was not something he had counted on, that she would tolerate him or accept his behavior as a model for her own. But why wouldn’t she, he thought, considering her there, imagining her through the eyes of those children as father and daughter emerged from the rustling leaves, smelling as clean as the sap of the towering pines, a healthy frosting of dirt under each fingernail, ruddy after a summer outdoors—wasn’t this the dream of every child: skipping school, sword battles with sticks in the woods, catching slippery things under rocks, and camping out in the yard? It had a pleasantness, a quaintness even, that was so foreign to him as a child, even in the stretches he spent in this same house and yard, and he would have never thought he would be able to provide even a sliver of it to his own child. He had worried that there wouldn’t be enough to eat, but there was always a little more and, though she was certainly lean now, and quick, she had even gained a little weight, a slight pot belly, and he felt that when there was hunger, it had instilled an appreciation of all the bounties they might discover, if only they were shrewd enough.

In the coupon drawer, there was a cheap pair of binoculars. It was comforting to think of his grandmother watching birds from the kitchen window, though he had never known her to do it. Lucian aimed them across the small valley at the laughing children. He saw garbage cans by the side of the house, a new shed, a kitchen garden, and through the window there was a table being set, illuminated by tapered red candles, with a shameful amount of food. He was relieved by the sight of it all. He knew they would make it through winter.