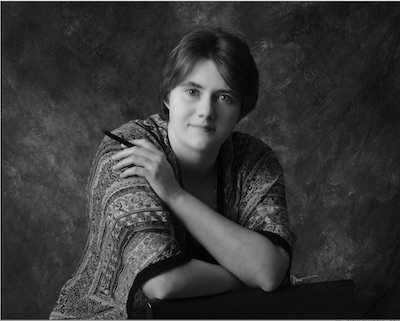

Kelly Weber

Contest - Prose Poem

Kelly Weber (she/they) is the author of We Are Changed to Deer at the Broken Place (Tupelo Press, forthcoming December 2022) and You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis, winner of the 2022 Omnidawn First/Second Book Prize (forthcoming October 2023). She is the reviews editor for Seneca Review and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in a Best American Poetry Author Spotlight, Gulf Coast Online, Electric Literature’s The Commuter, Hayden’s Ferry Review Online, Southeast Review, Salamander, The Journal, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from Colorado State University and lives with two rescue cats. More of their work can be found at kellymweber.com.

ARS POETICA

After the plastic surgeon poses me topless in front of the blue screen to document my breasts for insurance purposes, after she handles each one as both the most the delicate and most hated part of myself, after she says we will cut them off with two eighteen-inch incisions across my chest because to do otherwise would leave two empty windsocks of flesh, after she draws my nipple options for me, after she presses the cold tape measure from my clavicle down to areola and my skin puckers, after I decide not to keep the nipples that hurt in the cold, after I look over the foothills through her tinted window, after we talk about my drains and wound care, after she asks, again, which pronouns I would like her to list in the letter, after she tells me maybe spring for the surgery, after I pull my shirt back on and walk outside to the bees sugar-stunned fumbling over the October violets, after I text my mother again that I love her, after I find the frozen ground littered with dead bees two weeks later and cup one body in my hands, after I remember the winter I didn’t rip my skin open again and instead put a slash between my pronouns, after I put the bee back down and tuck all the bees’ comma bodies into the preceding paragraph block, I remember that a poem is left after whatever is unnecessary is cut away, and we don’t call this a mutilation—we call it a miracle.

“ One of the pleasures of the prose poem, for me, is how it's an especially useful form for straightforward reportage of a narrative or image. Plainspoken summary can underscore the tension and concerns of the poem in particularly interesting ways within the neat, unassuming box frame of the paragraph, or so I've always thought. With that kind of permission in mind, I wrote this poem in one sitting (something I almost never do), allowing myself to explore the memory as plainly as possible even as it surprised me and swerved into a more lyric space. In my nonbinary transition process, I've encountered the rhetoric of mutilation and self-negation again and again and again. In the process and form of this poem, I instead ask: what if not negation, but permission to finally be? ”