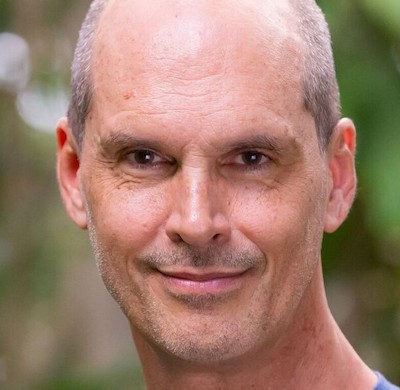

Frank Reilly

Fiction

Frank Reilly is a screenwriter and playwright. He won the Best Screenplay Award at the Austin Film Festival, and his screen adaptation of Caroline Paul’s novel East Wind, Rain has been acquired by Eleven Arts Studios, where it is in development. He lives in Kapa’a, Kaua’i.

The Stirling Stone

Diamond never cared for curling. I couldn’t get her to watch it during the Olympics. She didn’t even congratulate me when I told her I was bumped up to skip on my team at the curling club. She called it “shuffleboard for the frigid.” Still, I gave her the benefit of the doubt; she’d never set foot on a proper pond.

I took her out to the frozen water trap off the back nine at Lackawanna Golf so she could hear the rumble of the stone—forty-two pounds of Trefor granite—as it made its way over the ice. Just like the sound of rolling thunder in the distance, it’s a rumble that you feel. It hits you right in the pit of your stomach.

She started complaining before we got anywhere near the pond.

“There are hunters in these woods. You better not get me shot.”

She pulled up at the edge as I walked out on the frozen water.

“You’re gonna fall through.”

Her breath billowed like smoke from a fat stogie. The temperature had been in the mid-20s for weeks. The pond was three feet deep, tops. Maybe she was cracking wise about my weight.

“Take me back. I’m cold!”

I should have listened. She is cold.

~

Diamond has a son named Manny. He was thirteen when I met him.

“He’s big-boned,” Diamond told me. “Just like you.”

I hardly saw Manny for the first month when I’d come by to fetch his mom. He was always in his bedroom with the door shut, and she was always dragging me out of the house.

“What about Manny?” I’d ask.

“He’ll be fine. He’s learning on his computer.”

One night I knocked on Manny’s door while Diamond was still in the bathroom putting on her face. He had a serious gaming PC in there. He’d built it himself, piece by piece he told me, with money he made doing odd jobs. Shoveling snow, raking yards. I sat on his bed and watched him work his magic. He was good, and so wrapped up in his game—a military-themed, first-person-shooter—that it was easy to get him talking. He lodged one of the earpieces on his massive headset on the back of his neck so he could be in both worlds at once, talking PCs with me and toggling off mute when he had some vital piece of info he needed to share with the guys in his platoon.

“I had a problem with overheating for a while,” he said, “so, I replaced every fan, and then all the coolant tubing, before I realized the problem was the damn heatsink. Sniper, nine o’clock! The upside is, now I’m bullet-proof with cooling systems.”

I didn’t know what a heatsink was until I was in my twenties.

The more I called on Diamond, the clearer it became that Manny didn’t get out much. His room had that shut-in stink. I knew first-hand what a trap he was in. The better you get at online gaming, the harder it is to walk away from it. Pretty soon you need a screen in front of you to make a human connection. And the more you get your self-esteem on the web, the less capable you become in the real world. It’s a classic doom loop.

One night I caught him as he was leaving the bathroom. That was the first time I ever saw Manny out of the blue glare of his three monitors. He looked so pale, so small, despite his heft. I told him I needed his help with something and tried to walk him up the hall, away from his room. He started waving his arms like one of those inflatable tube-men they set up outside car dealerships.

“I’m in the middle of a game!”

Before he could say another word, I handed him my curling stone bag and he nearly fell over for the weight of it.

“What the hell’s in here, gold bars?”

“Might as well be,” I whispered conspiratorially.

While he was busy pulling the stone out by its handle, I went after the geek in him.

“There are only two quarries in the world that mine the kind of granite those are made from. One in Scotland, the other in Wales.”

“Is this from that sport where they slide on the ice, like . . .” He dropped down on a knee with one arm raised in a passable curler’s lunge.

Before he could think to mock it, I upped my game.

“It’s not just any ice. It’s pebbled.”

“Pebbled?”

“They spray it with water. The droplets freeze on the surface of the ice. Without pebbling, there’s too much friction. But when the stone runs over the pebbles, it melts them just enough to create a thin layer of water that it rides on—”

Manny’s eyes narrowed, like maybe I was shitting him.

“—and the pebbles affect the stone’s spin, which is exactly what makes it—”

“Curl?” he asked, a smile blooming on his face.

We talked about how the sweepers affect the stone’s momentum with their brooms by warming the ice and reducing friction even more. About how the wrong shoes will affect a shooter’s locomotion, and so the movement of his stone. About how a half inch of extra twist on your wrist can mean the difference between a championship or a flame-out.

Then I went in for the kill.

I told him about the Stirling Stone, a hunk of granite found at the bottom of a drained pond in Dunblane, Scotland, with the year 1511 engraved on its face. My favorite number, and history’s first curling artifact. That’s some serious Lady-in-the-Lake shit, right out of King Arthur. I could see it hooked him like it did me.

It felt like Manny was getting ready to invite himself to the club when his mom dragged me out of the house again. Off we went to another restaurant she was dying to try, then rushing back home before it got too late.

“I’d ask you in, but it’s past Manny’s bedtime.”

~

When I was showing up at her place with some regularity, Diamond started disappearing with no explanation. She’d throw on her coat, yell, “I’m heading out for a pack of smokes,” and go missing for two hours. Another red flag, I know, but—truth be told? I got a little thrill every time I heard the door close behind her. My pop pulled the same stunt when I was Manny’s age. When he did that, it meant I finally had the apartment to myself.

Once Diamond hit the bricks, I would get Manny to ditch his game controller so we could watch a few curling videos on YouTube. I figured he’d be better off learning from the greats. I would pause them every now and then to hammer home a point on technique. I waited until he looked at me before I spoke so I knew I had his attention, but also to get him to just look me in the eye. These caught-in-the-web kids, they’re clueless about social graces.

After a while, it was mainly me and Manny. I was a glorified babysitter.

So be it, I figured.

Look, I’m no catch. When I asked Diamond out for coffee, I kept a lid on my expectations. I think that’s a good rule generally. It makes it more likely that you’ll be pleasantly surprised when life puts a little extra spin on your stone. Better that I know where I stand, I thought, when I saw where things were headed. At least she wasn’t stringing me along. And I was glad to have Manny in my life. If I didn’t, who knows? I could have been another one of those massive-multi-player snipers looking to gun him down.

When Diamond pulled her disappearing act again one Saturday afternoon, I finally thought: well, we don’t need to stay in his room. I texted her that we were heading out for some fresh air.

Walking Manny into the club that first time, I fell in love with the place all over again. The Lackawanna Curling Association was established in 1908. The club still has its original exposed birch rafters hanging thirty feet above the ice, and a viewing gallery with a fireplace that looks out on the action. That room is fitted out with local history. Faded photos of dour men, capped and scowling, arms crossed or brooms in hand. You can trace generations back through the names on the banners on display. My dad used to take me to the club after Mom passed, mainly so he wouldn’t be drinking alone. He loved it there. I see his face in the mirrored back of the club’s trophy case sometimes, and he makes me smile.

It’s a hard world these days. You can’t know what’s coming at you when you walk down the street. Whether someone might breathe on you and get you sick, or yell at you for your privilege, or ride you for the color of your skin. Or just scare the crap out of you with the assault rifle they’re wearing like some high-fashion, open-carry accessory. But at the curling club, there’s order and reason and purpose. There are rules. Good rules. Kind rules. And if you don’t like ‘em, there’s the door.

I took Manny around. Introduced him to John at the desk, Margie in concessions. Had him shake hands. Grab on tight, three firm shakes and let go. Then we watched some matches. Everyone shoots in order, I told him: lead, then second, then vice, then skip. If anyone on either team makes a good shot, you congratulate them. If you win, you get a round of drinks for the other team. You shake hands and say “good game.”

I bought Manny his own pair of curling shoes. I was explaining the difference between the slider and the gripper as I got him laced, and when I looked up at him, his eyes were as big as saucers. He said he had to go the bathroom and ran off. When he came back, I figured we’d finally hit the sheets and throw a few. I was struggling to get up (they have those goddamn low seats with no arm rests) and just as I got to my feet, Manny was there in front of me. He threw his arms around me and mumbled a thank-you. I peeled him off me—I mean, Jesus, everyone was watching—and gave him my hand to shake. Firm, one-two-three and let go. That’s all there is to it. Then he was off like a shot toward the ice.

~

Our lead, Stan, was a student over at the community college and he had to quit the team because his grades were suffering. The rest of the league was okay with letting Manny sub. They quickly regretted it. The kid was a natural. He had an eye for finding the best line of delivery. It only took one conversation about scoring for him to understand the best way to play each stone he threw. As terminology went, the one thing he couldn’t remember was what curlers call the house: the series of colored, concentric rings—like a bullseye—at the far end of the sheet. The more stones you could cluster there, the higher the points scored. Manny kept calling it home.

“Bring ’em home!” he yelled out to Helen Gormley, our second, as she lunged off the hack. That just cracked her up, so much so that she nearly toppled over.

“A house is not a home,” she crooned back at Manny, laughing. Helen loves Luther Vandross. She’s always singing something.

The biggest kick I’d get, week after week, was watching Manny get comfortable in his own skin. He had some problems with balance, but when he could tuck his slider foot properly, he’d usually get it perfect. He’d hold his head with an almost regal bearing through his delivery, his eyes narrowed and his features set, like a young raptor spreading its wings for the first time.

When I was too loud with my praise early on, he blushed and threw me a disapproving look that hit me like a bolt of lightning. That brought on a pang that stayed with me for days. I thought this is as close as I may ever get to being a dad.

~

One weekend, something shifted.

Manny was hooked on Coca-Cola, a carry-over from his online gaming addiction. When we lost at the club, he was usually the first to get his drink order in, sometimes before the winning team had even offered to pick up a round. On this particular Saturday, Manny quietly ordered a seltzer with lime.

“What?” he asked, bemused, when all eyes turned to him.

It seemed that spending time with the gang at the club had made Manny self-conscious about his weight. I trace it back to one specific game, when Helen recommended that he use a stabilizer—a plastic contraption that he’d run along the ice in his non-throwing hand—for balance when he went into his lunge before a throw. When she voiced the idea, Manny turned as red as a barn door.

That’s when he started working out. Push-ups and sit-ups, he told me, until we did some research together that revealed that squats and pull-ups rounded out the top four exercises. I gave him a pair of old, chipped curling stones to use for extra weight while squatting. I also surprised him with a set of giant elastic bands, in various widths to provide the right resistance. We’d run down to the local elementary school a couple of times a week, where I taught him to use the bands to do assisted pull-ups on the playground monkey bars. He got more tenacious about it as the seasons changed and I’d drop him off at home after dark on some nights, him dripping sweat in the late September chill.

~

My bank statement arrived by post one dreary Tuesday. I never look at my mail. It’s mostly junk. And I never write checks, so why bother reading a statement? I had to look at this one, though, because it came right after a robocall from the bank warned me about suspicious activity.

The statement laid out the bare facts: one hundred dollars, more or less, being pulled from my account every couple of weeks. When I rooted back through the unopened statements that littered the floor of my hall closet, the story got plainer. ATM withdrawals that I never made, date stamped every few days, had begun months ago. Right around the start of my connection with Manny.

I hardly ever use my bank card. It’s buried in my wallet, which I keep stowed in my stone bag because I hate sitting on the damn thing. The bag is the best place for it as I’m always carting stones home from the club so I can texture their running surfaces.

When I checked on my bank card, I realized it was gone.

I changed my PIN number straight away. 1511 would no longer do. I don’t know why I even put the idea of that engraved number—that fabled year—out there.

What I needed to do, the world seemed to be telling me, was to bury what matters to me most. Down deep, like the Stirling Stone itself, at the bottom of some cold, Scottish loch.

I was pretty sure my wallet was the first thing Manny saw when I handed him my stone bag to lure him away from his online gaming. There were too many things he could spend jacked cash on to count. Things I’d never lay eyes on. A better graphics card buried in his PC build. A host of new online games. Who knows? Maybe his very own Pornhub account.

But when I sat him down and told him that something important had gone missing from my bag, he stared up at me with his head cocked like an oblivious Dalmatian. There wasn’t a hint of guilt or remorse anywhere near him. I couldn’t even make it to an accusation.

~

The day after I changed that PIN, Diamond called, furious from the outset, yelling about how I shouldn’t show my face anywhere near her place.

“And don’t even think about talking to Manny,” she said.

Manny must have shared the story of the Stirling Stone with his mom. In his excitement after hearing it, probably. Perhaps in an attempt to connect his world and my world with hers? Because maybe, just maybe, we could become a family?

Stranger things have happened.

It’s likely that her disappearing act when I visited early on was built around that bank card. Grab it, head out, pull out some cash—but not too much—and live a little. Then back home, replace the card and no one’s the wiser. The amounts withdrawn slowly crept up from week to week as she got bolder. When I started bringing Manny to the club and she lost access to my wallet, she must have thrown caution to the wind and just took it.

Diamond’s angry call was followed up a day later by one from a lawyer friend of hers, a tippler she had introduced me to a few weeks earlier at O’Leary’s Tavern. This ambulance chaser told me that a check on my cell phone’s GPS profile by a “buddy of his” at one of the telecoms confirmed my regular visits to the neighborhood elementary school.

“Not for nothing, friend, but what the hell is that all about?” he asked.

I hung up at “restraining order.”

I found myself behind the wheel of my car, then on the front steps of Diamond’s complex. I rapped on her front door but got no response. Some lights were on inside, and her car was parked out front. I resorted to pounding and waited in silence until I heard the muted ping of my text notification.

“Police on the way,” Diamond wrote.

Before I left for good, I stepped over to the front window and peeked inside, across the foyer and down the hall toward Manny’s room. His door was opened enough for the glow of his computer monitors to bathe my view in blue.

~

Six months later, I was at the club preparing to throw the hammer—the final stone—at the tail end of the season’s semi-finals. I had my foot in the hack, had cleared my mind, and was about to push off when Helen crept up beside me and laid her hand gently on my forearm.

I’d had this conversation with Helen before. I took her aside again.

“There’s a time for everything, Helen. But once a player steps into the hack, they’re in a holy place. You can’t disturb them, and you certainly can’t touch them. If you do, you’re breaking a—”

But I didn’t have Helen’s attention. She was looking over my shoulder. I followed her line of vision to the end of the adjacent sheet and there was Manny. He had slimmed down some. He looked taller, but maybe he was just standing taller. He had friends with him, a guy and two girls that were his age, and he had their complete attention. I was too far away to hear their conversation, but everything I needed to know was on display in the way he moved. He was making broad gestures with his hands. Pointing up at the rafters above the sheet. Miming a slide down the expanse of the ice, his fingers waggling as if to imply the spray of water that pebbles the surface. Demonstrating the shift in momentum from one stone to another in a bumping together of his fists. In less than a minute’s time, I watched him come into his own. The Lackawanna Curling Club was his. The world was his.

Manny slowly made his way back into the fold at the club. When he did appear, he revealed more of where he was headed in his bearing. He dressed sharper and moved with more assurance. His curling team, sponsored by Nate’s Electronics over on Wilson, was a force to be reckoned with. I think one of them was a physics major over at State U. Every now and then, after a respectable throw by one or the other of us, we’d exchange a nod of approval and a warm smile. A “good game” and a firm handshake. One-two-three and let go. Seltzers all around.

We’ve stayed connected over the years, Manny and I. Mainly through phone calls, sometimes texts. The occasional long and ponderous email. I’ve invited him over for dinner with Helen and me a few times, but I can never nail him down. No surprise there. Youth.

The last time I saw him in the flesh was one warm evening during spring break of his freshman year at college. He walked into the club with a bubbly young woman at his side. There was a great affection bouncing back and forth in the current between the two of them, but they hadn’t yet reached a place where that feeling could be expressed. There was, instead, a lot of smiling and awkwardness, a few incomplete sentences, and enough electricity to power a small city.

I remember standing before them, basking in the radiance of pure possibility, before we walked up to the viewing gallery to settle in for a good long talk. I remember thinking that I likely had one more shot at counteracting every terrible lesson Manny might have been taught about the world. I needed him to know the value of what he held in his hands now. I wanted him to call me if things got tough. I refused to have my half-baked attempt at connection with his mom serve as a model for his relationships. I—

Get a load of me. I needed, I wanted, I refused. I, I, I.

Once you push off from the hack, you’ve set your trajectory and your speed, and your stone is along for the ride. The handle is cradled in your palm, and you and your stone become one as you take a knee and slide forward toward the hog line—the blue stripe on the ice where the rules compel you to finally release your grip. Throughout that slide, the best curlers have one thought in mind: what can I do to have this stone come to rest where I know it needs to?

Your options are limited. A twist of the wrist. Pulling back on the handle to slow the momentum. A more forceful push off to gather speed.

Then you let go.

And the stone is on its own. Hopefully your aim is true, and it will make its way, slowly but surely, toward the house.

As Manny would say, toward home.