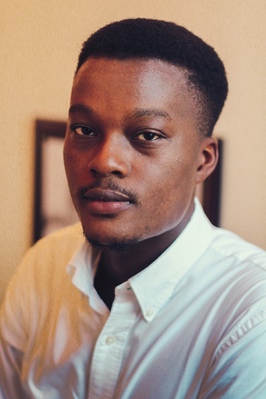

Afolabi Opanubi

Fiction

Afolabi Opanubi grew up in Port Harcourt, a city in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. He lived there up until he was sixteen, after which, he left for Canada to study and work. Currently, he lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he juggles a full-time job and writing fiction. His writing has appeared in The Drum Literary Magazine, Africa is a Country, Brittle Paper, 34th Parallel, and yNaija. He has also participated in writing groups, namely: Farafina writer’s workshop, and the Toronto Writer’s Cooperative.

Rust

1997

First, it’s the metallic sound whizzing above him that draws his attention. Ladi gazes up to find a plane coasting through the vast blue sky, with clouds thin as strands of grey hair. His eyes narrow as the sun burns into them, yet Ladi stares on, transfixed by the lithe movement of the plane and the trail of vapour behind it, like a footpath to heaven. He guesses where the plane is headed: Lagos, Cairo, New York, or London. Somewhere far away from Port Harcourt city, where he lives with his parents and younger sister. Ladi begins daydreaming again, a habit which has brought him bad luck one too many times. He imagines what travelling by air feels like and what Port Harcourt looks like from high up. Ladi, who’s never flown, pictures himself in a plane, looking out through the window at long, winding streets thousands of metres below, people looking as small as soldier ants, and creeks the colour of gunpowder flowing endlessly.

In his right hand is a toy windmill that he made by pinning a twig into a mango leaf cut into the shape of propellers. The windmill spins as Ladi chases the aircraft floating westward. He laughs with glee while trying to catch up with the object of his fascination before it is out of view. His friend, Tonye, who’s six (a year younger than him), calls out Ladi’s name from in front of a kiosk. Tonye pays for five perfect cubes of Choco-milo, pockets them and sprints after Ladi. Both boys scuttle up Uyo street, unpaved and flanked by bungalows, blocks of flats with gleaming zinc roofs, iron gates, and dense clumps of Hibiscus. Ladi’s heart races in his chest; he moves so quickly his bare feet feel like they barely touch the ground. His excitement slinks off his sun-beaten face and calves to Tonye, who begins chuckling with him.

A moment after, the laughter escaping Ladi ceases when a wave of sudden pain travels up his left leg. The ground under him shifts, or seems like it does, and Ladi collapses. Clutching his ankle, he screams out for help. The windmill falls from his hand and is blown away toward a bush.

A startled Tonye stops in his tracks. He walks over to Ladi and kneels beside him.

Tonye shrieks. “You stepped on a big nail.”

Ladi grits his teeth at a rusty nail half-buried in his sole. Blood streams from his wound to the stony, lateritic earth. He peers up at Tonye, when his friend continues speaking.

“You should have worn your slippers,” Tonye says, helping him up.

“Shut up,” he grunts, standing on one foot.

Tonye grimaces and lets go off him.

“I should keep quiet?” Tonye asks. “Okay, why don’t you walk on your own.”

Ladi shrugs and begins hopping to his father’s flat, four compounds away. He doesn’t go very far. The discomfort of hobbling on one leg proves too much of a hindrance. Without his friend’s assistance, he’s as helpless as a limping puppy. His face becomes clouded with embarrassment. He turns around to Tonye, whose arms are folded.

“Sorry,” Ladi mutters in a low voice.

Tonye grins and ambles to him. His sandaled feet cluck against the ground. He holds the crook of Ladi’s elbow and walks him home.

The plane is nowhere in sight when Ladi glances up at the sky. He drops his eyes and feels foolish for being carried away. Ladi thinks of how his mother will react to his injured foot; surely she will be mad at him. Her temper is like a sealed box of explosives: ticking, seemingly harmless from afar but staggering once it went off. She nurtures him and his younger sister, Tomi, as fiercely as she disciplines them. Pulling his arm away from Tonye, Ladi refuses to head home.

“What’s wrong?” Tonye asks, his forehead rumpled.

“I don’t want to go yet,” Ladi whines. “My mother will kill me for playing bare-foot.”

“You have to, whether you like it or not,” Tonye says, shrugging. “Who else will dress your wound?”

The back of Ladi’s neck films with sweat. He knows that it’s pointless delaying the inevitable. He has to face his mother. Breathing in deep, he holds on to Tonye and they continue their slow trek to his compound.

When his mother sees him approach the backyard, she shakes her head. She can tell what happened to him and the sort of circumstance in which it occurred before he speaks. She glares at him, her brows furrowed and her sculpted features stiffened. Her gentle forehead sloping down to her high cheek bones tightens. Ladi gulps spit; he recognizes that particular look on her face and knows it doesn’t bode well for him. It was the look his mother gave him whenever he misbehaved or whenever his proneness to day-dreaming put him in harm’s way.

Tonye greets Ladi’s mother Good afternoon Ma. She nods at him and asks how his mother is faring. Is she back to work? alluding to the riots that swept through the public school where Tonye’s mother taught and prevented staff from nearing the premises.

Tonye mutters a strong “yes.”

“We thank God. Greet her for me,” Ladi’s mother says, with a tone of finality.

Tonye folds in his lips and flashes a look of pity at Ladi before running home.

Afterwards, Ladi’s mother puts aside the tray of beans she picked stones from to inspect his foot.

“This is the third time you’ve hurt yourself this month,” she says, raising three fingers. “If this leg gets infected, you can get tetanus or gangrene. It could even be cut off.”

Ladi feels a pang of fear. His moistened eyes widen. He watches his mother rise up from a wooden stool, her slim and wide-hipped frame towering over him. She sucks her teeth and pads into the kitchen. She gives him no indication of when she’ll return to treat his wound.

Alone in the backyard, he gets regretful. He thinks of how he should be more careful with the way he plays, or “shine his eyes,” like his father advised him far too many times. Six months ago, on his way back from school, he was knocked down by a car. He was strolling home with his uncle and Tomi, when he skipped ahead of them and made for the other side of the road. Ladi was distracted by a story in his head—a made-up tale about changelings he’d read in a book—so that he didn’t realize a car was speeding towards him. The red Datsun flung him in the air onto the asphalt. Ladi remembers hearing the screech of car brakes before everything went silent. He recollects the street boys whom people claimed were members of the Black Axe cult, abandoning their game of draught under a tree, and running toward him to help. That overcast afternoon, the street boys seemed unthreatening, nothing like the violent youths the neighbourhood had made them out to be. His mother arrived at the scene, her loosened headscarf dangling from her hand like a dashed hope. She broke into tears, and her cry cracked an opening in his concussed mind. He heard her call out to his uncle to take Tomi home right away. Throughout the taxi ride to St Nicholas hospital on Bendel street, she asked him why he wanted to kill himself and ruin her. Her question wandered heedlessly in his head. Ladi didn’t say a word back. Now, he wishes that he said something to console her.

Flecks of rust and dry clay fall off the nail as Ladi strokes its blunt head. He attempts to pull it out but the pain around it deepens, stopping him. Ladi shuts his eyes. In one quick and thoughtless move, he yanks out the nail. He squeals at the fresh blood that oozes out. A throbbing sensation radiates up his foot. His mother walks out through the back door, a bowl of steaming water in her hand. She peers down at his stooped frame with a look of both sympathy and annoyance. Sighing, she sets the plastic bowl next to him. At once, Ladi is alarmed by a knife and towel resting at the bottom of the water. He draws his feet backward.

“What’s the knife for?” he asks.

“You’ll find out soon,” his mother answers, leaning over to pick up a jerry can of palm oil by the door.

She places the bottle down and begins cleaning his foot with the warm towel. She wipes the blood away, murmuring “sorry” when he winces. She then squeezes the towel over the bowl. In a delicate manner, she dabs his foot dry and rubs off the sweat coating his forehead with the ends of her slack t-shirt. Ladi’s nerves calm as a mild heat crawls over his skin. His eyes are glued to his mother’s face. Her quiet and focused look is the most peaceful thing he’s ever seen. It contrasts with the harsh stare she gave him earlier. A reassuring lightness fills his chest. He thinks of her affection as something permanent and unwavering, a birthright.

His mother pours the stained water from the bowl into a gutter running along the concrete fence. The knife rests, unused, on the edge of a stool. It catches the sunlight and gleams like a shard of glass. Ladi waits for his mother to pick it up and return it to the kitchen cabinet. He would be relieved if she did, because then he would no longer be confused about why it was brought out in the first place. His attention shifts to the clanging noise of a tailor walking past. Placed on the tailor’s shoulder is a small sewing machine with a wooden base that he strikes repeatedly with a metal disc. He is known by everyone as Obioma, a name appointed to tailors who hawk their services in markets and suburbs in Southern Nigeria. The next door neighbour, Mama Chika, lumbers out of her apartment, lace blouses hanging over her arms. She’s in her early fifties and heavyset. She waves Obioma over and they haggle over the price of mending her clothes. After they reach an agreement, she sits on a thin-legged chair with colourful pads woven from rubber to supervise him.

Ladi’s mother enters the kitchen and emerges with a kerosene stove. She lights it with a match. Then, she picks up the knife and places it over the fluttering, bluish flame of the stove. Ladi watches the fire lick the surface of the metal and turn it a sooty black. His stomach tightens when his mother pours palm oil over the heated knife.

“Stretch out your leg,” she orders him.

Ladi doesn’t. He shudders when she brings the knife with oil bubbling over it towards him. Ladi tries to back away, but his mother is quick; she holds down his right knee with one hand and presses the knife against his wound with the other. Ladi goes breathless as the metal singes his skin. His lower body feels like it is set aflame.

“This will sterilize the area,” his mother states matter-of-factly.

He yells for her to stop till his voice loses its strength. His loud cry wakes up Tomi, who sidles out to the verandah. Tomi’s neck is covered in talcum powder, which their mother applies on hot days to prevent heat rash from growing over Tomi’s skin. Tomi stares, puzzled, at Ladi and their mother locked into an unsettling position: a torturer bent over the tormented.

“Your brother refuses to listen to me,” their mother says. “I’ve warned him countless times to stop his rough play.”

Tomi doesn’t say a word. She bites the tip of her thumb and looks on with fear.

All the commotion attracts Mama Chika. Craning her neck, Mama Chika regards them with a confounded expression. She gets up from her chair and walks over to the back of their flat to find out what is going on.

“Wetin dey happen?” she asks in broken English, concern plastered over her face.

Ladi’s mother chuckles. Her laughter seems like an attempt to lighten a serious situation.

“Neighbour, this boy has to learn that life has no duplicate,” Ladi’s mother says, setting down the knife.

Mama Chika heaves a deep sigh and fastens her wrapper around her sagging waist.

“But Mama Ladi this is too much. You for take your son go clinic. This kind of treatment na the traditional way.”

Ladi’s mother chortles again, her voice thin and velvety.

“I’ve heard you,” she coos.

“I know the boy get strong head, but abeg take am easy,” Mama Chika pleads.

Mama Chika flashes a knowing smile at him, that appears to say I might not be around to save you next time. She leaves them to pay off the tailor. Ladi resents her for walking away, for not doing enough. She should have told his mother that his mother was being wicked for treating him so badly, he thinks. But she just walks away. As young as Ladi is, he knows that in his corner of the world, youth and innocence are reined in by the length of a rod and tough love. Last December, he saw a man, on a street not far from his, rub hot peppers onto his teenage daughter’s back and flog her reddened skin with a cane. “She’s a dirty, pathological liar,” he told the neighbours begging him to stop. People gathered around the man and appealed to his conscience, while his daughter wept, but no one stopped him.

His mother looks at him with a scowl.

“So this what you want?” she asks. “You want the compound to think I’m a bad mother, right?”

“No!’ Ladi exclaims.

“Keep quiet!”

Ladi stares vacantly at her. He’s confused by how she turned from being gentle and concerned to snappish, all in a matter of minutes. Watching her emotions vacillate is an assault on his brain. If only he wore his shoes, or behaved like a good boy, none of this would be happening, he reasons. Ladi feels responsible for angering her, for bringing out the part of her that is testy, hostile but vulnerable. A tear rolls down his face.

“Stop crying,” his mother scoffs. “Are you not a man?”

Ladi sulks and wipes his eyes with the back of his hands.

“I only want you to learn that life is fragile,” his mother continues. “One minute, you think everything is fine. The next, you do something stupid that costs you your life. Do you even know what death is?”

He nods and attempts to speak.

“I don’t think you do,” his mother snaps. “Close your eyes.”

‘Why?’ Ladi asks, glancing at his little sister as if she has an answer.

“I said shut your eyes.”

Ladi obeys her. He covers his ears too and remains like this for a stretch of time that feels uncountable. Ladi loses track of time; he’s unsure if a few minutes or an hour has gone by. He can’t hear anything, not even his mother breathing or the familiar sounds of the compound. A bleak darkness envelops him. He feels weightless and adrift. He is terrified at how long this feeling will last. An intense need to be rooted to the ground, to be a part of the present overwhelms him. Ladi wonders if this experience is close to dying, or if it comes before death. Is this the lesson his mother is trying to teach him? That death isn’t a part of life his childhood protects him from. Maybe this lesson is so very important it had to be burned into him.

Ladi waits for her to tell him to open his eyes, or say something to him. But only her cold silence echoes back. When he hears her speak, he’s unsure if the voice is hers or the product of his imagination.

“Ladi, what do you see?”

Words are unable to form in his mouth. His mother repeats herself, her voice louder and urgent.

“Nothing,” he mumbles. “I don’t see anything.”

“Good. Open your eyes.”

Ladi squints as he re-adjusts to the startling brightness of the air. A sense of relief washes over him. It’s as if his mother has given him a second chance to be loved by her again and to be a real human being centred in a maddening universe.

“You will bury me, not the other way around,” his mother says, her warm hands resting on his shoulders.

He limps to the living room after his mother tells him that he can leave. Tomi follows him. When he lies down on the red floral couch facing the Sanyo TV, Tomi sits next to him. She brings her legs close to her chin, wraps her arms around them and lays her head on the armrest. Ladi stares at her and she stares back. Tomi has a habit of imitating him, which usually infuriates Ladi. But watching her now, he can see that she isn’t mocking him or trying to be annoying. She only looks up to him for cues on how to carry herself, even if she’s a girl.

Ladi falls asleep. Hours later, he’s awoken by his father’s Volvo pulling up in front of their flat. His father, an engineer at an oil company, returns from work in the evening when the clouds have darkened. A song plays from the car stereo. The slow, lulling tune is by Jim Reeves, one of his father’s favourite country singers. His father told him once that in the early 80s, while he was in the University of Jos, he’d heard a roommate listening to country music on the radio and he’d taken to it. Somehow, this foreign sound from America’s South, which Nigerian returnees had brought to the country, struck a chord with him.

Ladi prostrates himself in greeting when his father walks into the living room. Tomi pauses eating her dinner, runs over to their father and kneels in front of him, as expected of a Yoruba daughter. Their father pats their backs and then plops onto the couch. He looks exhausted behind the round and wire-framed glasses slipping down his nose. Ladi takes his suitcase and carries it to the master bedroom. As he shuffles back, his father watches him closely.

“What happened to your leg?” his father asks, concerned.

Ladi narrates how he hurt himself. He describes what his mother did to him. He breathes hard as he speaks, his sentences broken by his painful recollections. After he’s done, his father removes his glasses and rubs the corners of his eyes. A brief smile forms on his father’s face. He draws Ladi close and embraces him.

“At least it’s over,” his father says. “Soon, you’ll forget all of this happened.”

His father turns on the TV with a remote. The evening news is on, and the grim face of General Sani Abacha, the country’s military dictator, appears on the screen. Standing behind him are three armed soldiers in dark sunglasses. The General is giving a speech on the imprisonment of journalists accused of treason. His monotone and heavy Northern accent pervades the living room. Across the country, people are afraid of speaking out against him in public. One could never be sure if a loyalist or a member of the State Security Service is within earshot.

Ladi’s mother ambles into the room from the kitchen, carrying a tray of food. She serves her husband his dinner: a task she has been performing herself since she sent her housemaid away for stealing money from the household. Before Ladi’s father eats the rice, beans, and goat stew in front of him, he asks her why she took things too far earlier in the day. She doesn’t give a reply. Instead, she sits quietly on the couch and props her chin on the palm of her right hand. She appears uninterested in talking about the incident. Ladi’s father sighs. His voice takes on a pacifying tone when he resumes speaking.

“Ro ra,” he implores. “Take it easy with the children.”

Ladi’s mother purses her lips.

“Mo ti gbo,” she says. “I’ve heard you.”

Ladi watches all traces of her sternness fade away from her face. She is, again, the woman with the most tranquil expression he’s ever seen. A feeling of triumph flickers within him. He sits beside his father, grateful that his parents will always be there as a buffer between him and all of his fears.

“ ‘Rust’ is set in Southern Nigeria during the 90s. It is about pain and fear, and how these two related experiences teach a child some hard truths about his community. ”