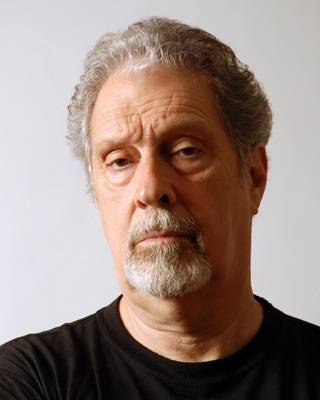

Bill Ratner

Creative Nonfiction

Bill Ratner is an eight-time winner of The Moth Story Slams in Los Angeles and a Best of Hollywood Fringe Festival 2012 Honoree for Solo Performance. His stories are featured on National Public Radio’s Strangers, Good Food, and The Business. His essays and short fiction are published in The Amor Fati, Pleiades, Southern Anthology, Spork, NiteBlade.com, National Cheng Kung Literary, Papier Maché Press, TV Marquee, and Coast Magazine. A personal essay was selected for publication in The Missouri Review’s audio essay contest. He is a voice on movie trailers, documentaries, and the voice of “Donnell Udina” on Mass Effect 1, 2 & 3, and “Flint” on G.I. Joe, Robot Chicken & Family Guy. Stories and more information at http://www.billratner.com.

Of This Earth

I spread the front page of the Sunday New York Times over my bathroom sink and set down the two urns that contained my in-laws’ ashes. Modern burial urns are designed to appear inviolable, their contents never to see the light of day. But if my wife and I were going to scatter my in-laws’ ashes, we would have to open their urns. With a screwdriver, I pried them apart. Inside each was a plastic bag closed with a twist tie. In Jack’s burial urn was a slip of paper that read: “The loved one’s remains respectfully prepared at Forest Lawn by Juan.” With a teaspoon, I took a tiny scoop of my mother-in-law Sophie’s remains and a pinch of my father-in-law Jack’s and stirred them together. Sophie’s ashes were a pale ashen gray—Jack’s, a sandy raw sienna—perhaps because Sophie had been cremated in The Bronx and Jack in Los Angeles. I pulled apart four empty gelatin capsules, placed them on the bathroom counter, and tapped Jack and Sophie’s ashes into the capsules. This was beginning to feel like a drug deal.

It was my wife Aleka’s desire and Jack and Sophie’s last wish to have their ashes scattered in a romantic locale overseas. My wife and her parents were very close. And they were serious travelers. Aleka served in the Peace Corps in West Africa. We met on a flight from Paris to Los Angeles; the first thing she said to me was: “I’ve been on four continents in the past week.” I fell instantly in love. Her father Jack was a salesman, and every summer he put his boss on notice that he was taking six weeks off to travel with Sophie. If they fired him, Jack would find another job. Sophie taught art in the New York State women’s prison system and was a practicing artist. She often determined where she and Jack would travel by where she could find the least expensive marble to sculpt. When Jack and Sophie were in their mid-eighties, we rented an apartment together in the Saint-Germaine district in Paris. Wearing matching berets and tattered tan trench coats, Sophie and Jack crowded hand-in-hand into our tiny elevator together every morning and took the metro to museums and sites, always with an unquenchable thirst for more.

Our last trip together as an extended family was to North Africa. One evening in their hotel room, Grandma Sophie draped Moroccan scarves around her head and bells on her ankles and danced for us. We were ecstatic. We felt as if we were in the Casbah. When we returned to the United States Sophie held one final gallery exhibition of her artwork that included a black-and-white mono-print made from a photograph. Sophie had photographed a sign on the lawn of a New York State mental hospital where she taught art to the inmates. The sign which was featured in her print read: “GO NO FARTHER THAN THIS.”

The night after Sophie’s opening, I found her in bed. She had slept eighteen hours. With the covers pulled up around her neck, she invited me to sit by her. “I have one complaint about my life,” she said. “I have wasted too much time hesitating, waiting for inspiration. Try to avoid this in your life.” Six weeks later Sophie died of heart disease at age eighty-four. Friends and family gathered at the Noho Gallery on Mercer Street in Lower Manhattan. Surrounded by her paintings, prints, and sculpture, we remembered her with stories. And I have never forgotten her bedside advice.

A year after Sophie’s death, Jack moved to Los Angeles to be closer to us. One evening we were in his apartment taking a Hatha Yoga class together. Attempting a triangle pose, I steadied my hand on his pine bookshelf. My fingers brushed a small wrapped package. “What’s this, Jack?”

“Oh, that’s Sophie. She wanted to have her ashes scattered somewhere beautiful. When I die, you can scatter me and Sophie together.” Jack lived for seven more years. He joined a writing group, traveled with our family, and had two girlfriends at the same time. A month after his ninetieth birthday, he telephoned his girlfriend Naomi—the one who liked to dress him up in sport coats and take him to first-run movies. He said to her, “I’d like to go out in a boat on the ocean with you.”

“Oh, Jack, you’re in a wheelchair, and I don’t like boats,” she said. That afternoon while riding up the steps on his stair-lift, cradling a book in his lap, Jack died. A generation had passed. My wife and I were now the elders of our family.

We had Jack’s body cremated at Forest Lawn Cemetery. The Family Services Specialist offered us a choice of burial urns ranging from a red plastic box for twenty-five dollars, to an etched gold urn costing $3,000. We chose the red plastic box. My in-laws’ burial urns rested next to each other on our bookshelf for a year. We began planning our summer vacation without them. My wife investigated legal disposal of her parents’ ashes, but strict international laws regulated scattering the remains of the dead, plus the prohibitive cost of hiring a licensed disposal service, eventually led us to our stealth disposal strategy.

We booked a flight to Paris. I placed the four gelatin capsules containing my in-laws’ remains inside my plastic vitamin box next to my Omega 1000 fish oil and vitamin C capsules. But I grew nervous about the chance that drug-sniffing TSA dogs would discover Jack and Sophie’s ashes in my luggage. I imagined TSA officers tossing their remains into the garbage and hauling me off in handcuffs. My in-laws’ ashes were becoming worrisome contraband. In order to confuse the sensitive noses of the TSA drug-sniffing dogs I sprinkled finely ground French roast coffee inside my vitamin box and stowed it deep inside my suitcase. If TSA officials discovered Jack and Sophie’s ashes, I would tell them the capsules contained bone meal from the vitamin store. And I would have to be willing to swallow one. Luckily Jack and Sophie’s remains went undetected and made it onto our flight to Paris without incident.

We landed at Charles De Gaulle Airport, rented a car, and drove south. Our first scattering of the ashes took place on the shore of the Mediterranean behind our Saint-Tropez hotel at sunset. In the early twentieth century, French Impressionist artists flocked to the Bay of Saint-Tropez to paint its sun-drenched vistas. Paintings by Matisse, Signac, and Bonnard were an inspiration to my mother-in-law Sophie, an artist herself, so this was the perfect spot. We bought a bottle of chilled rosé, and my wife, our two young daughters, and I walked out onto the dock behind our hotel. Under a warm summer sunset, we filled our glasses and made a toast to the memory of Grandma and Grandpa. I glanced over my shoulder to make sure no one was watching and pulled open the first capsule. I shook out the ashes over the water. There was a breeze. Ashes fell on my shoe. I wiggled my feet vigorously, and Jack and Sophie’s remains fluttered down into the brown waters of the Mediterranean. Now my in-laws would float in the Bay of Saint-Tropez, reflecting the same dazzling sunlight that inspired the Impressionists.

We executed our next surreptitious ash-dumping at Claude Monet’s nineteenth-century country manor in Giverny. The day of our visit, hundreds of visitors strolled over the red Japanese bridge and around the famous lily pond featured in Monet’s paintings. We lingered on the bridge, waiting for the foot traffic to thin out. With no one in sight, I reached into my backpack, took out a capsule, and dropped its contents into the pond. Jack and Sophie would now languish among Monet’s lily pads.

The inexpensive Parisian hotel that Jack and Sophie preferred no longer existed, so we rented a small tourist apartment in the Latin Quarter. On our first day in Paris, we visited the Louvre. Walking across the Pont Neuf toward the museum, we leaned over the railing of the ancient bridge, I pulled open a capsule, and we watched as Jack and Sophie’s ashes drifted down into the silvery black waters of the Seine.

A single capsule remained. Outside our apartment kitchen window was a flower box filled with geraniums. On our last morning in Paris, I sprinkled the ashes over the flower box. My six-year-old daughter was alarmed. “Dad, you can see Grandma and Grandpa.” Little trails of ash were clearly visible on the geranium petals and in the dirt. Out of courtesy to the next apartment guests, I rustled the geraniums and stirred the dirt, burying the ashes. Grandma and Grandpa would now reside in a flower box on a balcony looking out over the Left Bank of Paris, their favorite city in the world.

I miss Jack and Sophie. I treasure the memories of our travels together. We have quite a lot of them left in their baggies—enough to bring along on many journeys where we will take them to places they might otherwise never have had the chance to be.

“ I spent some of my happiest days travelling with my wife, my children, and my in-laws. For decades we all travelled as a multi-generational pack. From searching for a place to do our laundry, to discovering a restaurant with simple country food, every day on the road together was a delicious adventure with my wife’s family. They have passed, but they are still with us—in more ways than one. ”