Caitlin Garvey

Creative Nonfiction

Caitlin Garvey is a student of creative nonfiction in Northwestern University’s MFA program. She has an MA in English Literature from DePaul University, and she teaches English composition at a two-year college in Chicago. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Post Road Magazine, The Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, Apeiron Review, and others.

Doll Hospital

In August of 2014, Sheila von Wiese-Mack’s body was found shoved into a 27 by 18 inch suitcase, and then placed in the trunk of a taxi in Bali, Indonesia. Sheila’s daughter, Heather Mack, and Heather’s boyfriend, Tommy Schaefer, were both found guilty of Sheila’s murder. Heather, a Chicago native, has been coined the “Body-in-Suitcase Killer,” and a photograph of the bloody suitcase, taken by Bali police two days after the crime, was covered by international media and reposted to thousands of people’s social media pages. The taxi driver found Sheila, covered with blood, wrapped in a hotel bed sheet and tied up with duct tape. In order for Sheila’s body to fit the suitcase’s measurements and match the driver’s description, Heather and her boyfriend would have had to tuck her knees up to her chest. They would have had to tilt her so that one shoulder was touching the bottom of the suitcase and the other was pressed against its top. They would have had to bend her arms and unite her hands.

~

On my tenth Christmas, I received an American Girl Doll, Molly McIntire, representing the World War II Era. Her brown hair was contained in two braids, she had glasses, and she wore plaid. I undid her braids within the first hour that I unwrapped her, and I gave her a bath, dunking her head under the water and shampooing her hair. I took the lenses out of her glasses just to see if I could put them in again. I took her clothes off to see what was underneath. But what intrigued me most about Molly was her smooth, unblemished skin. My mother, then, was battling chronic lymphocytic leukemia, of which bruising was a consequence, and I remember wanting to transfer the soft, vinyl skin from my doll onto my mother, stripping the doll of a skin she didn’t deserve, a skin that belonged to someone who could really see me—someone who could yell when I broke her glasses, someone who could be, at the very least, aware when I took off her clothes. I knew the limitations of the skin transfer, so Molly became the victim of my frustrations. Every day for about a week, I tested Molly’s tolerance for abuse. I chopped off her hair. I slowly and methodically twisted her right leg so that it came off her body. I did the same to her left leg hours later. I twisted her head around and around, and then I advanced to removing her arms. On a day when I saw my mom vomiting from chemo (at that time known only to me as “necessary treatment”), I decided I was bored with Molly altogether. I did what the American Girl instructions warned against and pulled the white string on the back of her neck, decapitating her. Horrified, my mother demanded that I pack Molly on a trip to the “doll hospital,” so I crammed Molly’s head and nude body parts inside a cardboard box and had my mother ship her away for reconstruction.

~

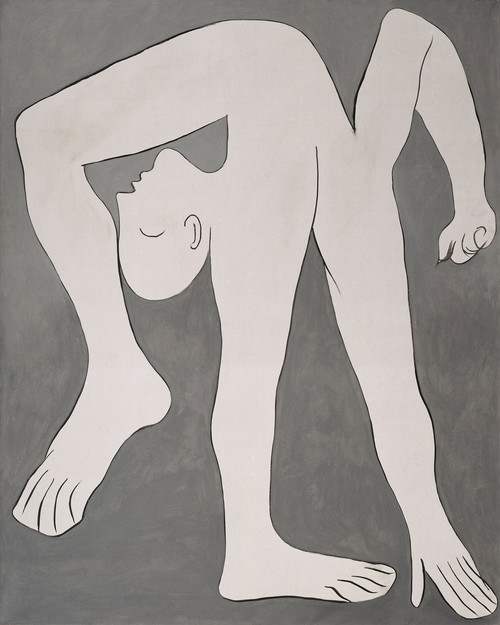

In the late 1920s, Pablo Picasso began his work with Surrealism, creating subjects that were both fantastic and visionary, with a goal to blur the line between dreams and reality. He completed and debuted his painting, “L’acrobate,” using oil on canvas, in the year 1930, its dimensions 63 3⁄4 x 51 3⁄16 inches. The body is missing a torso and neck, so the figure’s entire body is just elongated legs and arms. It’s a simple composition, a one-line sketch, and because it’s so simple, it seems easy to play around with—he tested several versions of this, disassembling his figure’s parts and putting the pieces back together in new ways, just to see what would happen. The limbs are twisted and arranged in unusual positions, reconfigured on the canvas, maybe meant to show the contradictions between movement and rigidity. Surrealists manipulated their subjects, taking the freedom of artistic expression, intentionally distorting bodies in an effort to disturb. In Picasso’s painting, the pale figure appears nude and contrasts with the darker, grey-ish background. Picasso constructed the painting so that it could be hung from any angle. Regardless of which way you turn it, the figure is confined to the frame. You can rotate the image as many times as you want, but the figure will still be distorted.

Picasso, Pablo. L’acrobate. 1930. Musée National Picasso. 1000 Museums. 2015.

~

My room, 375, in the psychiatric unit of Memorial Hospital, was painted dark blue. When I asked him why, my psychiatrist responded that blue is calming and it would help me drift off to sleep, and then he faintly smiled and said, “Make yourself at home.” The room was small, maybe 150 square feet, and behind the twin bed with its thin white sheet was a small window, maybe 24 x 32 inches. There was a dresser next to the bed, and on top of it was a vase of decorative plastic flowers. Above the vase on the wall was a small, framed photograph of an ocean; no one was in the picture—it was just sea and sky, a blueness that was almost absorbed by the surrounding wall. I held my belongings—an iPod, a book, a journal, a depression assessment form, and a pen—in a mesh bag, and after I laid it down on the bed, I walked toward the window and noticed that it wasn’t a window at all, but a tacked-on wall graphic, a constructed scene of trees and sky. As I sat waiting for my appointment with the psychiatrist, I filled out the assessment. The form wanted to know which feelings applied to me and which ones didn’t, and to what degree, from zero to three. “0” did not apply to me at all; “1” applied to me to some degree, or some of the time; “2” applied to me a considerable degree, or a good part of the time; and “3” applied to me very much, or most of the time. The first statement read: “You have thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way,” and I checked the box that held the “3.”

~

When asked about Heather and Sheila’s relationship, their family friend told a reporter, “It was like they were locked in an inescapable pattern, a gridlock. It was like a disaster waiting to happen.” In a People magazine interview, Heather paints a picture of Sheila as an overbearing mother—making Heather sleep with her every night, threatening to kill herself if Heather ever moved out of their home, controlling her movements—terrified of her daughter but more fearful of abandonment. According to the FBI indictment, Heather sent text messages to her boyfriend, Tommy, about her mother’s behavior. Tommy wrote, “This bitch [victim] so abusive.” Mack replied, “im living it i know how abusive she is.” Mack added, “theres proof ive been abusive too . . . in the past ive fought back . . . pushed her back.” Other news outlets paint Heather as a monster—a troubled and delinquent teen who, on multiple occasions, fought with her mother so viciously that police were called. She toyed with her mother for years, accused of threatening her life repeatedly, calling her names, and blackmailing her for money.

Heather and I both grew up in Oak Park, Illinois, within a mile of each other. I have friends who were close to Sheila, and some to Heather. Heather was 19 years old when she killed her mother, and I was 24 when I heard about it. A year before she died, Sheila attended a block party that my friend’s family was hosting. While there, she told a few people about how worried she was about Heather—at that time, Heather wasn’t going to school and she was seeing a boy whom Sheila labeled a “bad influence.” According to a block party attendee, Sheila had an image of a good mother-daughter relationship, and she knew hers didn’t match. She planned their vacation to Bali in an attempt to mend their relationship.

~

I imagine the embalmer standing over my mother, logging in his notebook any details of the body: discolorations, cuts, bruises, scars, and then using disinfectant spray to clean her skin, eyes, and mouth. When I saw her body in the casket, I looked closely. The embalmer had removed her peach fuzz, accenting her makeup—makeup that she never would have worn in the first place, over-applied, colorful rather than neutral, and loud. So loud, in fact, that it spoke to me as I knelt beside her casket; “Get me out of this box,” she said through the color. When I thought no one was looking, I took my index finger and wiped off some of the blue eye shadow, the last time I touched her. I imagine the embalmer closing her eyes. To avoid dehydration of the lids, he would have to put some sort of cream on her eyelids, maybe even glue to prevent separation. Same for the mouth: kept together with a suture or a cream. The embalmer’s goal is restoration, his end result—a done-up body—can be retouched and ultimately presented to the world, to the deceased’s loved ones as they remembered him/her. The deceased is dressed in an outfit chosen by the family, including underwear, and the viewing of the restoration, a realization of death’s finality, is supposed to commence the loved ones’ grieving processes. Restoration is a physical covering of scars, in a way distorting the reality of the body’s battle with death. Restoration hides the wounds that my mother developed from her war with leukemia as well as her more recent fight with inflammatory breast cancer. After her double mastectomy, which left deep scars across her chest, the cancer spread to her chest, which created a gaping chest wound that ultimately led to a skin graft. Parts of her skin were removed and used to cover up wounds in other areas, “fresh skin” replacing unhealthy tissue. My mother was prescribed a Wound V.A.C. (Vacuum-Assisted Closure) for the healing process. To draw the wound edges together and to suck out infectious materials, the V.A.C. was attached to a tube, which was sealed onto the wound with a sponge. The V.A.C, the size of a shoe box, was like a portable vacuum, making sucking noises as my mom held onto it, to remind her of its presence. The embalmer disposed of the V.A.C., and with it, the infectious materials that it managed to suck out, and then covered up the evidence on her body. After we prayed above this restored body, we put dirt over the coffin, lowered it into the ground, and said amen.

~

Surrealists were said to develop methods to liberate imagination. They wanted to free people from restrictive customs. In several pieces, Picasso pulls apart the body, mostly the female body, and puts it in tortured positions. There’s power in invention. There’s a freedom in creating art, in creating something new, in manipulating your subject and putting together the pieces of your experience. The artist determines his subject’s position, but the canvas’ dimensions serve as a restriction. The artist can twist the limbs of the subject and even detach their heads, but the canvas traps them and forces them to exist out of time and space, freezing the elements so that they can be gawked at and admired.

~

I remember unwrapping Molly. She was in a big box with a bow on it, and my grandmother, the procurer of the gift, subtly pointed to it and smiled, as if to say, “That’s the box you need to be opening. The only one that matters.” In my family, Christmas gift distributing was a lesson in politeness. The kids—my two sisters and I—were to take the gifts out from under the tree, read the name on the label, and pass them out to everyone before retrieving our own. Once everyone was seated and next to his or her gift pile, we began unwrapping the boxes simultaneously on the count of three. I remember being gracious. I remember screaming in genuine excitement once I opened the box and saw Molly’s face staring back at me. I was a tomboy, much more interested in toy trucks than tea parties and generally turned up my nose at anything pink, but dolls were the exception. My dad would go on long trips for work, and as a souvenir he would bring back porcelain dolls for my older sister and me. We established quite a collection, since he traveled frequently, and they were different each time—some with blonde hair, some with dark, some chubbier, some shorter, some with their hair pulled back in a tight bun and some curled, and some in dresses and some in overalls. My oldest sister, a perfectionist, kept her dolls lined up in a row according to height order in her bedroom, and no one could touch them, not even herself. I, on the other hand, tried to find out what made the dolls tick, and I quickly realized that I could stretch the limits of my imagination with them. I played “school” with them, where I was their teacher and they answered in the way that I wanted; I practiced kissing on them; I invented their desires, goals, hardships, and family relationships. Invention impelled their conversion from doll to human.

~

There was no clock in room 375. I was on their time. Nurses performed “checks” at 7 a.m., told me to eat lunch at noon, and announced lights out at 11 p.m. I counted seconds in my head, trying to gain some semblance of control over the world in which I had to adapt in order to exit. My psychiatrist’s cocktail of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and sleeping aids didn’t prove successful, and looking at me with sympathetic eyes, he softly said, “There’s another option.” Electroconvulsive therapy, as he described it, is a brief application of an electric stimulus to produce a seizure. There is some controversy over its use, he said, but many people have found it very effective for treatment-resistant depression. He did not give the statistics, but he added, “It’s reversed some people’s symptoms entirely. It’s changed their lives.” He spoke of the stigma that surrounds it, saying that during the 1940s-50s, “ECT” was administered without anesthesia, which led to memory loss and, in his words, “other side effects.” He tried to calm me by leading me into a room. “We’ll show you how it works,” he said, “then you’ll see.” In the room, a male doll, a substitute patient about 3 feet tall, was lying on a hospital bed and staring blankly at the wall with big blue eyes. Electrodes were attached to his plastic scalp and the machine used for ECT, box-shaped and small in size, lay next to him. My psychiatrist signaled that he was turning on the machine, and he told me to watch as the plastic patient underwent a brief convulsion. The machine produced a dull beeping sound for about fifteen seconds, and the doll remained still. After turning the machine off, my psychiatrist gave me a thumbs-up. “See?” he said. “No real disturbance.” I stared back at the doll’s blue eyes, with the awareness that I would ultimately take his place in a desperate attempt to separate my brain and its distorted thoughts from my body. The goal for my psychiatrist is reconstruction, I thought, fixing me up as best he can, and then presenting the “new me” to the world. If I smiled on my way out of the hospital, I would appear healed.

~

Before I sent Molly to the doll hospital, I killed her. I was aware of this. I had given her life through inventing her story. She didn’t get along with her mom, so her mom sent her to boarding school, which is how she ended up with me in the first place. Her dad wasn’t around. To boarding school she wore her plaid sweater and skirt, and she brought pencils and a notepad; she was excellent at math, but received lower grades in other subjects: Language Arts, History, and Science. “Ms. McIntire,” I addressed her, “please speak to me in my office after class.” I scolded her for her low grades and told her that I was aware of her home life, but that didn’t excuse her low marks and I expected better. I persuaded my parents to let me get the bed that went along with the Molly doll, and I tucked her in at night after changing her into her red and white pajamas. Molly wanted to be a doctor once she got her grades up. She wanted to help sick people. She was going to find a cure for cancer. When Molly returned from the doll hospital, she came once again in a box, wearing a patient robe and holding a “Get Well Soon” balloon. When I opened the box, I wondered if she had remembered what I had done to her. I also wondered what it would be like to do it again.

~

Sheila’s body was ultimately flown back to Chicago. An autopsy found asphyxiation to be the cause of death, after a blunt blow broke her nose. The medical examination showed other broken bones in her head and face, and there were wounds on her hands, which indicate that she tried to defend herself. An Indonesian court sentenced Tommy to 18 years in prison, and Heather received a 10-year sentence, both for premeditated murder.

Heather Mack now sits in a small jail cell in Bali, about 6 by 8 feet in size, that she shares with eight other women. She announced that she was pregnant right before the police took her in for questioning, and her daughter, Stella, was born in a prison hospital. Heather made the decision to keep Stella in the cell with her until she reached the age of two—the maximum age that children are allowed to stay in prison with their mothers.

According to the Chicago Tribune, the court was more lenient with Mack because she had just given birth. The verdict read: “Her newborn baby badly needs a mother’s love and breastfeeding.” I imagine Heather looking down at her mother’s body in its suitcase. I imagine baby Stella, doll-like in size, confined to a cell, imprisoned herself before even speaking, and in the arms of her mom, a mom who put her own mother in a suitcase and tried to ship her away.

“ As the piece says, Sheila Mack was at a block party in 2012, and she told a friend of mine that she was having trouble with her daughter, Heather. Hearing the news about Heather felt strange; I hadn't known her, but I was somehow connected to her through hometown friends. I began to think more deeply about this connection, but also about the relationships between mothers and daughters. I discovered even more connections while exploring confinement and the limits of the body and mind. ”