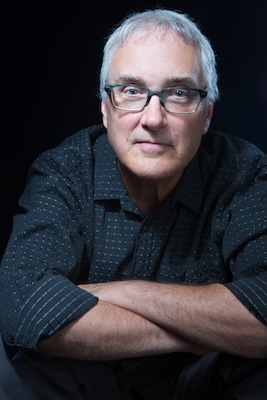

Ron MacLean

Fiction

Ron MacLean is author of the story collections We Might as Well Light Something on Fire, Why the Long Face?, and the forthcoming Apocalypso, as well as the novels Headlong and Blue Winnetka Skies. His fiction has appeared in Barrelhouse, GQ, Narrative, Fiction International, and elsewhere. He holds a Doctor of Arts from the University at Albany, SUNY, and teaches at Grub Street in Boston.

Apocalypso

1.

I’ve got a front-row seat at the fish bar at the end of the world, where happy hour is long past and closing time unclear. The piano man plays scales in a sharkskin suit. My dentist is ducking my calls, but I’ve got good whiskey, a bowl of goldfish, and a priceless view of the hills: aflame in blood orange, sepia, coal black. Thick smoke squats atop the tree line and a steady stream of would-be evacuees snakes toward a downed bridge. Those who thought their end would be a watery grave sit silent and count their losses. We see all and can do nothing; no means to get a message to the outside world.

I would want you to know I’m not alone. There’s barely elbow space at the bar, but my colleague and I more or less keep up with demand. We took over shortly after the real bartenders fled. He’s got a shock of dark hair that falls over one eye when he talks. We try to keep it light, loose. He has a way of winking which doesn’t feel fake.

It’s comfortable here. Spacious. Think grand ballroom of a swank hotel. Ocean-blue carpeting, sky-high ceilings. Cut-glass chandeliers and studded, red leather stools. A trout brook babbles, lush with attendant greenery, through a field of high-top tables where the well heeled mingle with the hoi polloi in ways unlikely apart from a cataclysm. Here’s a hedge-fund guy in a bespoke tux sipping champagne with an upright bassist. A wall of windows four stories high protects us—for now—from the conflagration outside. Before long we’ll need fresh glasses.

On plasma TV screens, a pair of pundits clamor for the camera. Overpowdered, they argue implications and root causes, analyze swing votes in key counties while, behind their heads, the world burns. A text crawl tallies the dead. I’m trying to keep people lubricated, the only form of kindness that makes sense.

A short bald man with a round head cases the service bar, crestfallen. He reminds me of someone—the guy on the evening news who lost his family in a car crash. I mix him a mai-tai, fresh orange slice, two paper umbrellas. It works: his shoulders straighten.

A boy, head bowed, follows an elderly woman past the olives, a cat cradled in his arms.

On the screens, images of a candlelight vigil somewhere in Minnesota, where purple-clad pilgrims pay tribute to The Artist Formerly Known As on the anniversary of his death. They tote tiny flames as the sky falls around them.

In here, the piano man plays the opening bars of “When Doves Cry.” I try to catch his eye to redirect him to something more like “Delirious”.

My colleague tilts a Collins glass in my direction, eyebrow cocked. “What do you do with a messed-up mojito,” he asks, peppery hair over the one eye. I add a splash of Aperol. He tastes. Beams. “Apocalypso,” he christens, and slides the glass along the bar.

Beyond the trout brook, a lone waiter prowls the floor, stick-thin and stoop-shouldered, bow tie crisp, distributing votive candles and complimentary Fireball shots. Money became moot hours ago.

The pundits, on break, weave through our crowd. The greater, long and lean, fishes for compliments while the lesser snags a spot at the bar. He’s got feathered hair and sliding foundation. He’s a three-day-old mylar balloon, and I’m out of helium. I mix him my best champagne cocktail.

A soothing female voice sounds over concealed speakers: “Bikram yoga will begin in 11 minutes just past the shrimp station.”

The bald man charges the wall of windows, thrumming like a diesel. His skull smacks the glass with a thud as he bounces off. The glass is reinforced, double-walled for safety. Stunned, he strokes the carpet with his fingers, like he’s petting some newborn animal. The vein in his forehead throbs.

A woman appears at the bar with an empty glass and a full, fresh-water smile. Hair and teeth and arms in all the best places. Her smile reaches into me in ways I can’t afford. She’s on the short side; I may have missed her on a previous pass.

But I’m cool. “What’ll you have?”

She nudges her glass toward me. A necklace of pearls. Thickish thumbs I could fall for. “Ravaged Manhattan,” she says.

“Done.”

Her forearms look for a dry place to land. Out of rags, I rip off a sleeve and wipe down the bar. The wall of windows is hard to ignore. She’s trying, but the set of her shoulders tells me she’s torn.

I get it. Out there, the end is hazy through smoke and ash. What I can make out, beyond my ability to ignore, is a thickening queue approaching the downed bridge. The woman follows my gaze while I float a layer of Fernet atop her drink.

“They don’t know they’re doomed,” I explain.

She touches my chest, her hand where my heart would be. Shaken and stirred, I pull back. She raises her glass. “To all that might have been.” We clink.

The piano man does Bowie, “Ashes to Ashes.” In 93 seconds we’ll draw straws to see who goes back in time to try to burn better bridges.

2.

At the raw bar, we’re pouring drinks like there’s no tomorrow, grasping for anything that might serve as a buffer.

Outside, the ground is on fire. The resourceful construct catwalks above the flames, but it’s futile; struts burn and crumble beneath them while they work. My colleague catches me looking.

“There’s no time for that.” An eel wraps his arm like a tourniquet, its eyes abulge, jaws clenched on the flesh at the inside of his elbow. Still, he shakes a metal canister with flair and vigor. I wonder do others see what the effort costs him. “A drink made exclusively from stolen ingredients,” he challenges.

I don’t miss a beat. “Apocaklepto.”

Everyone here is impaired in one way or another. Gashes, scrapes, open wounds. Some wear hearts on absent sleeves, desperate to tell their tales. Rumors abound. The word tsunami tossed around like beer nuts.

Two honchos drink highballs and slide a cigar box across a cocktail table. On the TV screens, our pundits plead for votes from hypothetical viewers while the host asks them to compare cavities.

Me, I’m breaking out the good whiskey. I’ve missed a call from my dentist.

The host, in a Savile Row suit, wants to see what the exit polls say. The greater pundit grins. “They’re all exit polls now.” They tally votes. Compare margins. Where allegiances have shifted and by what increments.

Meanwhile, a man bends my colleague’s ear and sips rye. “My ex-girlfriend attacked me with her shoe,” he says. He’s dressed for a party in gabardine trunks and Smartwool sleeves. “A five-inch stiletto heel.” He works his arm back and forth to mimic the motion. He’s matter-of-fact, like shit happens, but multiple stab wounds—small, round, bleeding holes—dot his face and neck.

The round-headed bald man hurls himself at the glass to no avail; the lesser pundit drags himself to the bar, where a kind gent surrenders a seat. “The vote,” this pundit says to no one in particular, “is the primary benefit of citizenship.” His microfiber suit sags. He’s got tired eyes and a sense of purpose that no longer knows where to land.

Over by the olive trees, the conga dancers pop kalamatas and talk technique. A harried woman tries to cook eggs on a broken hot plate and the greater pundit navigates the room in a convertible GTO with a missing door.

My colleague pops up from below with what may be the world’s last cola. Neatly navigating his eel, he pours a splash into the rum-and-lime: “Apocalibre!” he declares. The lesser pundit flees.

Outside, sinkholes swallow smallish towns. With 73% of the vote in, the outcome is too close to call.

Fresh-water woman appears like dessert. Hair askew. She gestures at a trio of leeches attached to my exposed arm. “Those weren’t there before.”

I shrug. I can hardly feel them.

Sadness seeps from her smile. She requests a blood-and-sand. I supply my own B-positive. She touches my hand and sips.

Round-head takes a seat next to her, forehead bruised from clashes with the safety windows. “I’ll give you fifty dollars if you can make me cry.” His face rings a bell. He takes my lemon zester to his forearm, scrapes at skin. I pry the tool free and set it down, gentle as I can, in a nearby chafing dish. I make him warm milk with cardamom.

I would want you to know this work feels like a privilege.

Teary-eyed, the lesser pundit bursts in as if the building’s on fire: “Whoever took my Prius has two minutes to bring it back!” He carries a car door under one arm. He’s bleeding from his left ear; his pearl-buttoned dress shirt is mangled and torn. “Seriously,” he says. “This isn’t funny anymore.” He’s beyond the reach of cocktails.

The man with the stiletto holes wanders, wet and exposed. The waiter wraps him in a blanket and hands him a glass.

At the bar, the lesser pundit wraps a tender arm around our bald man, who sips his cardamom milk. The pundit is near tears. “Without you, we’re nothing,” he says, rubbing margarita salt on the head wound. I cut him off.

3.

Poolside at the dive bar at the end of the world, we’re out of mixers so you have to take it straight. The dancers are perfecting variations on the half-gainer, the bathrooms are out of order, and all the ladders are missing. Above us, the glass roof creaks and groans. I turn to my colleague: “We’re going to have to get resourceful.”

Outside, it’s night sweats and blood poisonings. The earth is coal black, tangerine orange. People cling to trees like frightened koalas. Thick smoke saves us from seeing in too much detail. The bald-headed round man slides slowly down the window wall, viscous and vision impaired.

At the bar, we’re playing Which Bowie Are You while on failing TV screens the greater pundit executes a flawless 2-1/2 somersault from the pike position. There’s a pool going to guess who’ll last longest. Smart money’s on the dancers.

The lesser pundit pulls up in his driver’s side door. Mangled right arm through the open window, he calls, “Could someone point me toward a crêpe station?” Women I’ll never meet offer themselves to the pool. We’re all treading water: I’m looking for a certain set of pearls and trying not to see how little it matters.

Dark helicopters sweep the area outside, quelling flame or bringing it.

A diver, flustered, drops a drink. Another rocks glass shattered. My colleague shrugs: “Apocalamity.” I clean up with brush and dustbin while he replaces the beverage. We’re seamless. It’s a shame we can’t sustain it.

At the deep end, two dancers do full gainers off the high board, even their splashes in sync. The greater pundit appears unfazed.

A woman to my right is white with worry. I recognize her from her failed breakfast. Now she’s kneading dough on the bar. “I shouldn’t be here,” she says. “I have so much work to do.” Her weariness makes me want to weep. I pour her a sloe gin.

The lesser pundit heads for the pool with a death grip on his door. The dancers take a smoke break. TV screens distort and pixelate.

Over the speakers, a measured female voice says, “For your protection, please put on swim goggles. If you need goggles, please approach the nearest staff member.” We pour a round for everyone—any staff members are long gone.

The bald man flings himself at the pool, limbs flailing, torso extended, reaching for some ideal of grace. He lands in a poignant belly flop. With 98 percent of precincts reporting we are unable to project a winner.

Cacophony from above. Glass flies in sparkling shards reflecting lavender, bright orange. The Artist Formerly Known As crashes through the roof and floats toward us, purple suit aflutter. It’s hard to take my eye off what’s coming, but I do, to ask a woman who’s been waiting with a gashed arm, “What’s your poison?” She eyes me like a turkey leg.

The bruise-headed bald man licks his wounds, tells my colleague a tale: “I ask her ‘how long can you hold a grudge?’ and she says, ‘I don’t know yet.’”

Glass falls like rain as The Purple One drifts down. I catch a glimpse of ruffled shirt. Thin mustache and insouciant front curl. My colleague casts me a weighty look and searches in vain for supplies. Helicopters hover at roof level. Their blades stir smoke and flame. Flickering plasma screens show my dentist performing bridge work on the greater pundit, who instantly shoots up in the polls.

At the pool, seven synchronized dancers execute a stunning reverse twist. A cadre of scared civilians follow; they jostle for position and plummet, free fall, in various stages of undress.

Flames lick the roof hole. Silence washes over us.

The lesser pundit: “I once saw a movie that felt this way.”

The Purple One descends. Bellbottoms. Platform shoes in violet suede. My colleague and I watch, spellbound. He lands awkwardly between the trout brook and the olive trees. An ankle buckles. Our bald man sees and scurries over for support. Fire breaches, falls toward the floor.

A lilac lackey, big hair and a suit like blown glass, lays a leather backpack on the bar. “The boss wanted you to have this.” I zip it open. My colleague removes bottles of rum and pineapple juice, cream of coconut and OJ, along with two nutmegs. He grabs a shaker, gathers every glass we’ve got and starts mixing Painkillers. I will miss him.

Now—of course—the woman in fresh-water pearls is beside me at the service bar. I have so little to offer.

“It’s funny what you find yourself wanting now,” she says. Her voice is the gentlest sound I’ll ever hear. “What is it for you?”

I hesitate, but now is not a time for withholding. “I’d give anything to have my teeth straightened.” I feel a flush in my cheeks, despite it all. “You?”

She smiles. “Four inches taller. Just for a day.”

Things happen in clusters: pundits climb curtains; dancers take tuck positions; honchos haggle for getaway cars that don’t exist.

Our lesser pundit soaks it all in. Our bald man stabs at a door with the good scissors. A fiery helicopter smashes through two chandeliers as the clock on the wall runs dry. My colleague wraps his eel-free arm around my shoulder. I wrap a bloodless arm around his. I would want you to know I am grateful.

“Last call,” we say in unison.

“ I wrote the first version of the first paragraph of ‘Apocalypso’ on election night the first time around with he-who-must-not-be-named. Drafts of the story took several forms over a few years until finally, I realized that the end of the world story I wanted to tell was not one of cowering in fear, but one of claiming and creating community, taking care of each other as best we could right to the end. ”