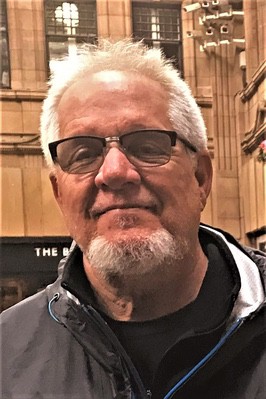

Jim Beane

Fiction

Jim Beane’s stories have appeared in numerous literary magazines, and the anthologies DC Noir and Workers Write: Tales from the Construction Site, winner of the 2017 Tillie Olsen Award for Creative Writing. His five-story chapbook, By the sea, by the sea . . . , was published by Wordrunners eChapbooks as their winter fiction selection for 2018, and his collection of short stories, Almost Men: stories, received a nod as semi-finalist for the Hidden River Arts 2019 Hawk Mountain Fiction prize. He is a Pushcart Prize nominee, a Virginia Center for the Creative Arts fellow, and a workshop leader at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda, Maryland. He mentors for the Veteran’s Writing Project and is an instructor in Creative Writing for the Armed Services Arts Partnership. Jim lives outside of Baltimore with his wife and their dog Lily in a loosely structured family commune.

Close to Her Heart

I tripped on the ragged edge of curb and plowed into Miss Caroline. Shouldn’t hurry. Never hurry. I get discombobulated when I hurry. Never hurry. She nicked Lloyd in the neck with the tip of her scissors. Holy Hell. Old Lloyd acted like she’d stabbed him. Lloyd’s dramatic, but it was only a little poke. He tumbled from his chair to the concrete clutching his neck.

Miss Caroline sets up metal chairs in the mission driveway on Saturday mornings. One chair in the drive so she can sweep up easy and the others under the shade of the elms lining the drive. She gives free haircuts to anybody down and out who wants one, like me, like Lloyd. She’s got her reasons.

I fumbled an apology for bumping into her.

“It’s OK, Hector,” she said. “No harm done.”

Lloyd glared at me. Lloyd’s a hard man, critical of everything and everybody, ready for the fight. But I don’t want to fight Lloyd. Sometimes I think Lloyd wants to fight me, a whole different story. But this story is not about Lloyd, or me. This story’s about Miss Caroline and her brother Robbie.

Lloyd grabbed the overturned chair and righted it in the driveway. He sat down with a huff and rubbed his neck, then mumbled mean things about me.

I waited until Lloyd quieted down, then blurted the reason out as to why I was in such a big hurry. “I saw Robbie.”

Lloyd and Miss Caroline froze. Their heads turned to look at me.

“That’s right,” I said. “Saw him at the Victor Street camp, over on the east side. You know, Lloyd, out past the freight yards.”

“I don’t know nothin’ of the kind.” Lloyd and I have been to the Victor Street underpass together, two, three times. More than that, but Lloyd’s a disagreeable man. He leaned away from Miss Caroline and spit. I shrugged.

“Soon’s I seen him, I hightailed it here, fast as my legs could carry me.” I gasped for air to show off my effort and sneaked a look at Miss Caroline to see her reaction. “Don’t laugh, Lloyd. I ran the track back in school.”

Lloyd rolled his eyes. He pointed his finger at me, his eyes narrow slits.

“Quit upsettin’ Miss Caroline,” he said. Lloyd removed his hand from his neck and inspected it. He wiped a spot of blood on his pants. “Look what you done to me, Hector, with all your foolishness.”

I ignored him. Robbie’s not his brother. Robbie’s Miss Caroline’s brother.

She shows the crinkled photograph she has of him to everyone sits in her chair. She says, “Good Morning,” then flashes Robbie’s photo and says the same five words every time, “Have you seen this boy?”

She’s always disappointed. Painful to see. She carries the picture in a plastic sleeve on a beaded chain around her neck and tucks it in her shirt pocket close to her heart. Robbie’s a pup in the photo. Red, curly hair and freckles splashed across his face. Clear eyes, like clean water, staring holes right through you, same as Miss Caroline’s.

“You can’t be sure it was Robbie, Hector,” Lloyd said. He spit the words at me.

“Let’s see the picture, Miss Caroline,” I said.

She pulled the photo from her pocket. I studied Robbie and studied him some more. I knew Miss Caroline needed the boy I saw at Victor Street to be her Robbie, and that was good enough for me.

“Definitely him,” I said. By then, I’d built my story and was sticking with it.

She slipped his picture in her shirt pocket. “Take me to the camp, Hector. We’ll ask around.”

“Awww . . .” Lloyd said.

Let me explain something about me and Lloyd. We been shelter hopping for the last fourteen months, together. Buddy-system, like the army. No funny business, neither one of us is like that, but we’re getting older and it’s good to have somebody watching your back, even if that somebody happens to be Lloyd. Lloyd likes arguing, I don’t, so, long as I keep my mouth shut, smooth sailing.

“I am sure.”

“Then let’s go,” Miss Caroline said.

“Wait, wait, wait.” Lloyd was waving his hands. “Victor Street ain’t no place for you, Miss Caroline. What was you doin’ over there anyways, Hector.” I hate when he questions what I’ve done. I shook him off.

“Couple nights ago, Short Hand John showed up at the bus terminal. He told me Mary had drifted back into town and took up with the camp people over to Victor Street. So, I went to see her.”

Lloyd dismissed the notion with a huff. His mutt Freebie wandered up beside him.

“Did you speak to Robbie?” Miss Caroline said.

“Sounds like Hector had more interest in Mary.”

“Wasn’t like that,” I said.

“Yeah, well what was it like?” Lloyd had a way of talking that made his words sneer at you.

“Well… I ran into Mary right before I spotted Robbie. She grabbed me up in a big hug and offered me a bowl of soup. Completely confused the situation, didn’t register with me the boy I’d just seen was Robbie until I was halfway done eating. Soon as I finished eating, I searched the camp but couldn’t find him.”

“You searched the camp?”

“Yes. I searched the camp. What, you don’t believe me?”

“You should’a dropped your plate and gone after him right away.”

“I was eating.”

“He got away whiles you were eating.”

“That’s right.”

“That’s the point, Hector. Took your sweet time about the whole mess, din’t you?”

“Lloyd, please.” Miss Caroline touched his arm.

“Miss Caroline, Robbie ain’t in that underpass camp,” he said. “Come finish my haircut. Forget about Hector’s nonsense. Believe me, he din’t see your Robbie.”

Lloyd doesn’t believe anything anybody says. Doesn’t matter who’s saying, me included. I looked down. The dog nibbled the frayed duct tape wrapped around the toe of Lloyd’s shoe.

“Ain’t safe,” Lloyd said. “You don’t know them people, Miss Caroline. And camp people ain’t friendly. ’Specially to them pokin’ their noses around. And Hector here.” Lloyd waved his hand at me. “He won’t be no help when you need it.”

Miss Caroline’s eyes shifted to the string of cars parked on the street. She noted the empty chairs under the trees. Then, checked her watch.

“Hector?” she said and nodded at the line of cars.

I hesitated, camp people were unpredictable. What help would I be if things turned sour? Wasn’t like I wouldn’t try to help Miss Caroline. Course I would, I wasn’t afraid of camp people. And what’s the worse that happens? They stomp me and take what’s mine. I been stomped before and I’ve got nothing to lose. But Lloyd’s right, I’m hardly the man I once was. Miss Caroline is a good person, she shouldn’t get hurt because of me. I looked to Lloyd. He looked to the ground and shook his head.

“Hold on, hold on,” he said. “I better come along, and where I go, the dog goes. Right, boy?” Freebie perked up and crept from under the haircut chair. I know I felt better.

“Fine,” Miss Caroline said. “Bring the dog. But let’s get going, it’s already past two.” She led us to one of the cars on the street. I stood outside the car, staring inside through the side window, rubbing the dent in the door.

“Don’t worry Hector,” she said. “You can’t hurt anything.”

She popped the locks and I dropped into the front seat. Lloyd squeezed in the back and held Freebie in his lap. The dog shook like it had the DTs.

Miss Caroline drove fast. Her phone spit directions in robot voice. First time I’d heard that, but it didn’t take long to recognize I didn’t like a robot voice telling me what to do. Thankfully, the trip was quick because of Miss Caroline’s speeding. She drove to the dead end of Victor Street and parked alongside a tall chain link fence with razor wire spun along the top. Fifty-gallon oil drums, standing in line across the road, painted black and yellow, kept cars from going farther. She didn’t bother locking the doors. Matter of fact, before Lloyd or I could get out of the car, she’d slipped through the drums and waited on the other side where the asphalt road turned to gravel. Beyond the fence corner, the camp began.

Looking up, concrete twists of roads and ramps blocked every bit of sunlight trying to peek through. The camp remained in constant shadow. Tents and cardboard huts crowded together. Church people brought the tents, all bright and colorful when first set up. But now, stained and streaked, gray as ash from soot and car exhaust. Wasn’t a soul in sight.

Miss Caroline stopped outside the first line of tents. Lloyd sidled up next to her. Freebie followed. Their eyes wandered over the camp. Freebie licked his paw.

“Where’s Mary’s spot, Hector?” Miss Caroline said.

I pointed to a heap of blankets stirring outside Mary’s tent. The blankets grew tall and shook about until a grim-faced man stood staring at us. I knew him, I’d seen him that morning at Mary’s. The man shambled toward us.

“Where’s Mary?” I said.

He squinted. Freebie growled. He came closer to me. He wasn’t old, like I first thought. Up close, I saw he was still a boy.

“What you want with her?” he said. His voice gruff, his chin stuck too far out. Freebie barked at him and the boy snatched a stick off the ground as thick as my arm. He shook it once at Lloyd’s dog.

“Hey,” Lloyd said.

“Hey what?” He shook the stick at Lloyd, daring him to try something. He looked down and snarled at Freebie. The dog tucked behind Lloyd’s legs.

I cleared my throat and said, “We’re looking for someone. This woman’s brother.” I nodded to Miss Caroline. “I saw him right here this morning.” The boy’s eyes darted from Miss Caroline to Lloyd, to me.

“Uh huh,” he said. He wiped the sleeve of his coat across his mouth. “You got a cigarette?”

“No, he ain’t got no cigarettes,” Lloyd snapped. He still steamed from the way the boy threatened Freebie.

Miss Caroline pulled Robbie’s photograph from her pocket and held it out.

“Have you seen this boy?” she said.

“Hey. Hey. Step back a little.” The boy hefted the stick and blocked Miss Caroline from getting closer. Freebie barked. The boy kicked dirt at him.

“Have you seen him?” Miss Caroline said.

“You got a cigarette?” he said.

“No, I don’t smoke, it’s bad for you.”

Lloyd laughed.

The boy scratched at his neck and tilted his head. He stared at the picture a long time, then tapped it with his fingertip. “I seen someone looks like this, but he ain’t no kid.”

“He’s thirty,” Miss Caroline said. “When did you see him last?”

“Yesterday. No, today, early, this mornin’. That’s right. He was beggin’ food from old Mary, but she din’t give him none.”

I clapped my hands. “Told you,” I said.

Lloyd rolled his eyes.

“Wait, wait, wait,” the boy said. “I never said he was still here.”

“Well . . . where is he?” Miss Caroline said.

The boy stepped backward and surveyed the three of us.

“How would I know?” he said. “You sure you ain’t got no cigarettes?”

“Listen to me,” Lloyd said. “We ain’t got no cigarettes. Just answer her question.” Lloyd used loud like a club.

“You got no call talking to me like that,” the boy said. He raised his stick to chest level. Freebie bared his teeth. “Better call that goddamn dog off.”

“Go on, get outta my way,” Lloyd said. He shoved past the boy deeper into the camp.

I noticed people starting to pop up behind the tents. More drifted in from other directions.

“Maybe we should go,” I called out to Miss Caroline.

And then, the world shakes, and your life shifts, again, like life does.

Robbie walks right out from behind Mary’s tent and rams right into me.

“Hey,” I yelled. Robbie stiffened like a kid caught shoplifting. Startled, he tried hard to recognize someone in me, then made his move to run. But I moved quick and bear-hugged him from behind. Robbie swung me around some, grunting and groaning. Boy had me wheezing, but I held on. He smelled like fruit gone bad.

Finally, Lloyd joined in. Freebie barked up a storm. Lloyd helped me hold Robbie still to give Miss Caroline a long look. She touched his cheek. Robbie jerked away like he’d been scalded. But Miss Caroline’s eyes never left his face.

“What do you want with me?” he yelled.

Her fingertips touched his chest. Her head dropped forward, just a bit, and she looked at the ground between them.

“Fuck off,” he said. With a quick twist, he lurched loose from Lloyd and me and took off in an awkward trot. He disappeared behind a row of shacks, never once looking back.

Miss Caroline’s eyes lifted from the ground, her hands slipped into her pockets and she watched Robbie fade away into the scatter of dirty tents. When he was out of sight, she turned and walked out of the camp towards the car, without waiting, or asking if we were coming along.

During the ride back to the mission, Lloyd stared out his side window and stroked Freebie asleep in his lap. I stared straight ahead. None of us spoke, we’d all had enough talk for one day.

By five-thirty, she’d parked in the row of cars alongside the mission. A crowd of street people and drifters milled around the front steps waiting for their one hot meal of the day. The night man Carl stood on the top step of the crumbling concrete porch, arms crossed, scanning the crowd. The mission doors were closed.

“So, Miss Caroline, you gonna finish cutting my hair?” Lloyd said.

Miss Caroline turned her car off but kept both hands on the steering wheel. Her eyes closed.

Freebie, Lloyd and I waited. The car was hot and smelled of dog.

She raked her fingers through her hair. A soft smile settled on her face and her eyes opened slowly.

“Yes, Lloyd, I’m going to finish cutting your hair.”

She opened her door and, in the fading twilight, walked to the empty haircut chair still sitting on the driveway. Lloyd limped along behind her. Freebie followed Lloyd, I followed Freebie. Miss Caroline grabbed the towel draped across the back of the chair and swatted the seat.

Lloyd sat down. And I sat in one of the waiting chairs. Freebie trotted into the bushes.

Miss Caroline lifted a clump of hair from Lloyd’s head with her comb and snipped it close to his scalp. Lloyd jerked upright, his eyes big as eggs.

“Sorry Lloyd,” she said and patted his shoulder. “Hold still, I’ll try to be more careful.”

“Sit still and let her finish.” I didn’t mean to yell but I’d grown a little sick of Lloyd at that moment.

Lloyd flinched when I spoke and shot me a look, but remarkably, he kept his mouth closed. He looked toward the mission doors and settled into the haircut chair with a huff. Miss Caroline cut Lloyd’s hair close to the scalp on the sides and shaved his sideburns off at the tops of his ears, the way he liked.

“All done,” she said.

Lloyd ran his hands across his head. He grinned and yanked his sock hat over his fresh cut. Freebie reappeared and wagged his tail.

“I like a haircut,” Lloyd said.

“You’re like a new man, Lloyd,” Miss Caroline said. Carl blew his whistle, and the men out front of the mission began to line up.

“Comin?” Lloyd said to me. He nodded toward the mission’s front doors. Men were trying to shuffle past Carl. “Gettin’ late,” he said. “You know how Carl is.”

“Go on,” I said. “Think I’ll get a little trim.”

Miss Caroline patted the chair back.

“Save me a place,” I said to Lloyd’s back.

Lloyd kept walking as if he hadn’t heard. Freebie trotted after Lloyd. At the foot of the stairs, the dog stopped, looked up at Carl and started barking. Carl stared until the dog whimpered and Lloyd nudged the animal off the stairs with his foot.

Carl blew his whistle two short blasts, the signal for everybody’s last chance to get inside. Lloyd stood next to Carl on the stoop. He looked at me and tapped his wrist, as if he ever owned a watch, then ducked inside.

I plopped down in the haircut chair.

“Don’t worry,” I said to Miss Caroline in as sure a voice as I could conjure. “We’ll find Robbie.”

She patted my shoulder, draped the towel around my neck, clipped it tight and smoothed it flat. Her hands remained on me, warm against my shoulders.

“Thanks Hector. Always hope, right?”

I didn’t answer, I couldn’t. I wasn’t familiar enough with the feeling of hope to answer in any truthful way.

A cool evening breeze pushed past us. Miss Caroline pulled her fingers through the hair on the sides of my head, from the temples to my neck, nails against my skin. Felt good, I could’ve sat there all night. But she patted my shoulder and I knew that we were done.

“Next Saturday,” she said. “We won’t be rushed. Unlike Lloyd, you look better with longer hair. More distinguished. But Lloyd’s right about Carl, better hurry.” I didn’t want to hurry off, leave her like that, upset about Robbie and all. But she was right about Carl. Once the doors were locked there was no getting in. I eased up from the chair and headed for the stairs. I didn’t hurry. I know what happens when I hurry.

“ I’ve lived in a few places in my life and visited many more. Most have been in or very near urban areas. Lots of people and lots of needs. The homeless, even when in plain view, remain one of our culture’s large classes of invisibles. This story comes from my wanting to see and hear them as people not labels, and to give others the same opportunity. In these troubled times, it is our duty to open our eyes. We are all God’s children, not just some of us. ”