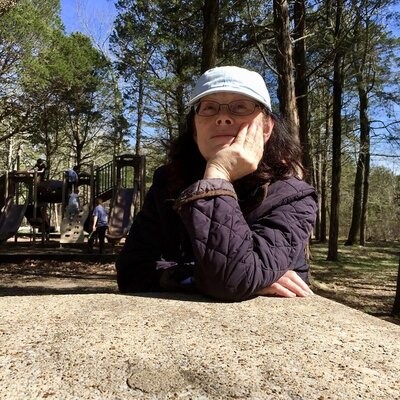

Jeanette Tryon

Fiction

Jeanette Tryon completed her MFA at Rutgers Camden in 2013. Her work has appeared in Sycamore Review, The Timberline Review, Peregrine XXXI, Apeiron Review, and The Evansville Review. She is a grandmother, a retired nurse, and a musician.

On the Road of Flotsam: Maybe There Will be Pie

The roads to home are deformed. New construction, areas of decay, altered traffic patterns leave me unbalanced and bewildered. I am on foot and I am trying to find my way home. Mom is with me. She is on the stretcher I am pushing. I must tell you that only her head is on the stretcher. I apologize for that. I know it is ridiculous. That I am pushing a stretcher through city streets is also ridiculous, so I apologize again. Perhaps I am caught in a dream, but if I am, it is one of those dreams that feels more real than my awake life.

The stretcher is old. It has small, distorted wheels, and it is hard to push. I am getting tired. And thirsty. And hungry. We should be in a car. Or, at the very least, I should be pushing Mom in her wheelchair. I feel like I have been condemned to an absurd task.

“I’m hungry,” says Mom.

“I’m hungry too. We will be home soon.”

I am lying and she must know I am lying. But she doesn’t say anything.

I specifically want to find Livingston Avenue. Or Joyce Kilmer. They run parallel, and both lead to the family home. Albany runs diagonally through them. Albany used to help me decades ago when I lost my bearings. If I ended up on Albany, I could always figure out how to get to Joyce Kilmer or Livingston.

I stop and look around, hoping to see a hint of Albany. It feels like it’s right there, up ahead, off to the right but hazy, unapproachable, sterile, ghostlike.

Don’t get distracted, I warn myself, by ghosts of the diagonal. I have to keep moving.

I’m not sure how Mom ended up on this old stretcher. Usually I push her about in a wheelchair. The stretcher is cumbersome, and it rattles. I hated stretchers like this, years ago, when I worked in the ER, and later, when I worked in an OR. But what’s really creepy is that the stretcher only holds Mom’s head. Where the hell is the rest of her?

Better to pretend that all of this is sort of normal.

Or symbolic. The stretcher is flotsam from my past. Mom’s head is a cypher. Something like that. Years ago, when lost in a weird dream or memory, I would carry a surgical basin in my arms. I would walk on a dark road, alone, heading nowhere but carrying a stupid surgical basin in my arms. Those basins were a totem of my years as an OR nurse. Now, this old stretcher—I don’t know. A totem of, maybe, all of it? The back and forth of it. Taking a patient to the recovery room. Receiving a patient in near cardiac arrest on an ambulance stretcher. Taking a patient to the morgue.

The real surgical basins came wrapped in muslin, stacked in piles. I’d take two or three from the pile and set them in rolling circular stands. I’d remove the tape and open the folds of muslin like petals of a flower, being careful not to contaminate the cold, sterile surface of the bowl. The saline in the basins would be used to bathe surgical wounds or to moisten sterile sponges. Think of a high priestess ceremonially rinsing a sacred cloth for use in, well, something probably pretty awful. That is what it was like to watch the scrub nurse set a sterile sponge in the saline, remove it, then twist out the excess saline before passing the sponge to the surgeon. I usually circulated, which meant I took care of the gloved and gowned surgical team. My job was to handle and troubleshoot everything that was not sterile. When the surgeon handed a bloodied sponge back to the priestess, the sponge would be discarded into a small trash bin. I had to keep track of the bloody sponges. I would line the rim of the bin with individual sponges—opened up to make sure a needle or some other small item was not caught in any of them—until I had five red ribbons. Then I would put the five sponges into a small plastic bag. I lined the bags up against a wall to be counted as a group at the end of the case. The bloody sponges really could disappear inside the abdominal cavity. If not found, they wreaked havoc on the patient.

All that counting, done squatting or leaning over, made my back scream. Toward the end of my tour, I learned to sit on a step stool while bagging or counting.

“Why are you thinking about that stuff?” Mom asks.

“You heard me thinking?”

“Ribbons of sponges, sacred saline, blah, blah, blah.”

“That’s mean.”

“Pay attention to what you are doing. Let’s get home.”

Mom is a nurse too. A better nurse than I ever was. Smart, ambitious. She was a nurse during the polio epidemic in the US in the 1950s. She put people in iron lungs, took care of people in iron lungs. She nursed acute cases when other nurses did not want to. She ultimately became a supervisor at a polio hospital; her patients adored her.

“It was a stupid party,” Mom says. “Why did you make me go?”

“Seemed like a good idea at the time,” I say.

“But now I’m dead.”

“Don’t be dramatic. We’ll get home. You can die later.”

“Did you get some lemon meringue pie to take home?”

“Uh, no.”

She sighs, disappointed, and rolls her head to the side.

It was such a stupid party. I shouldn’t have made her go.

It was Mother’s Day. For whatever reason, none of Mom’s brood said they’d be by to visit. Which was awesome. The week had been strenuous—Mom had two doctor appointments, a bad episode of shortness of breath, a near fall—and I was tired. I’d found myself feeling fuzzy off and on. I had even been bothered by a bit of chest pain and shortness of breath. That sounds ominous, I know, but sometimes when I am amped up and anxious, I get some of that.

But the week hadn’t been all that bad. My biggest worry had been Mother’s Day. Mom lived with me, and Mother’s Day was exhausting. My small house would fill up with siblings and their children, a ton of food, many assorted gifts for Mom, and cranky or overexcited grandchildren. I’d be frantic, trying to keep everything nice. I had loved the idea of a quiet Mother’s Day: just the two of us, one a mother of six, myself a mother of one, home alone with the crazy old dog, with his big head and sweet, silly heart. I’d make soup and we’d watch a movie.

I made the soup. From a can. But before we could eat it, my brother Gary called. The eldest.

“Come over. Have lunch with us. Please, please, please.”

Now how does a former ER, ICU, and OR nurse (that’s me) not have the courage to say no?

“Well . . .”

“We have the lemon meringue pie from the bakery Mom likes.”

My brother sounded so earnest, so boundless with enthusiasm for Mother’s Day and the pie he had bought, that I just couldn’t get myself to say no. Plus, this brother, believe it or not, almost died of polio. For real. He was in an iron lung when he was all of five years old. Mom was no longer a polio nurse at the time. He didn’t catch it from her. He picked up the virus in the last gasp of an epidemic before polio vaccines changed everything. My poor Mom with a bunch of babies. She had to stay home while my father drove my brother to the ER. Turned out he had bulbar polio, which interferes with breathing and is particularly deadly. He didn’t die, because a young female pediatrician (very rare at that time) insisted that he have a tracheostomy. Also, my aunt pinned a St. Jude medallion to his hospital gown just before he was wheeled away. When he came out of surgery, he was awake, and his lips were no longer blue. Mom revered the young doctor, and St. Jude, forever more.

But he had a very long recovery. When he came home, he was rail thin. So, even five decades later, it is still hard to refuse this brother who survived polio when he sounds so earnest.

So I made Mom get out of bed and get dressed. Cleaned the dentures, combed her hair, wiped her face. Packed up a small canister of oxygen in its nifty carrying case and made sure I had the requisite dual lumen tubing. I also packed up her just-in-case pills, snacks, and water in the white plastic backpack we used for doctor trips. I put her in her wheelchair, ferried her out to the car, and headed to my brother’s house.

“Do you have any water?” Mom’s head wants to know.

The plastic white backpack, which hours ago was coherent in shape, is now ancient, browned and frayed, barely holding Mom’s supplies. It is slung over my shoulder. I take a small water bottle from it, open it, and carefully guide it to Mom’s mouth so that she can take sips of water. Mom asks for a cookie, so I dig out a Chessman cookie from the bag and press it to her lips. She breaks off small bites. This makes her happy and her eyes sparkle. I adjust her oxygen tubing. She doesn’t have a torso, but her tank of oxygen is on the lower shelf of the stretcher. Seems like a lot of trouble for just a head, but there it is. I have to be careful. With Mom’s head, of course, but also with the tank. Can’t let it fall off, get broken. I dropped a tank once, decades ago while at my very first nursing job, and it became a rocket shooting down the hallway of the old hospital. Corky, the respiratory therapist, who was unattractive and whiny and married to someone equally unattractive and whiny, was furious at me. Furious. I hated being young and stupid at that moment.

Now I am old and stupid, having bent to a brother’s wishes. And I am lost with my mother’s head in tow. People are outside, drinking beer, playing basketball, yelling or cooing at children. I hope they don’t notice us. But after a while, I hope they do notice us—maybe they will help. I want both things at once.

This is what happened at the party:

When we arrived at my brother’s home, the house was filled with relatives of my brother’s wife. Dozens of them. All ages and tangents of relationship. Some older and sicker than Mom. There was a lot of noise, many strange faces to greet, and awful small talk to make. We were stunned but already in the house. Backing out—literally, as in wheeling the chair backwards to the car—seemed like an awful thing to do to my sister-in-law’s relatives. So we settled in and made excruciatingly polite conversation. My plan was to stay for about 45 minutes and then declare that Mom was tired, time to go home.

Then calamity struck: Mom needed the powder room, urgently. But it was already occupied. The occupant was a sickly elder with her own helper daughter. They could not be hurried. There was no way I could get Mom upstairs to use the other bathroom. I knocked on the little door of the powder room. Mom was beside me in her wheelchair, urgent need on her face. I tried to knock both forcefully and politely—I used the hard knuckle of my index finger. No answer, just some low moaning, murmuring. How I wanted to oust this other elder out. I felt like I had dropped a tank again, at this moment, having come to this party.

But my brother and wife had meant well. They must have realized they wouldn’t have time to come see Mom for Mother’s Day. They thought inviting us over was a good idea. It never occurred to them that a house full of guests would not be good for a dying parent and an exhausted caregiver.

“Stop blaming yourself,” Mom says. “You always blame yourself.”

“No I don’t.”

“Yes you do.”

She might be right. It’s a way of controlling things, I suppose. Blame yourself. That means you could have done better. That means a loved one has not failed you. I apologize when I should hold people accountable—to whatever. Like my brother pressuring me to bring Mom for lunch, without ever mentioning there was a house full of people there.

Whatever. Right now, I need to focus on getting home. I would really, really love to find Joyce Kilmer Avenue, the road to home named after the poet who wrote “Trees.”

“I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree”

Mom is reciting. This is nice. This is soothing. She did this when her brood was growing up. She loved iambic beats. I loved the sound of her iambic beats.

“A tree whose hungry mouth is prest—”

Mom stops. Frowns. “So you really didn’t pack any of the pie to take home?”

“Sorry, no.”

Pretty much all we’d had at home had been that Campbell’s Chicken Noodle soup. There had been lots of nice food at my brother’s house. And there was that pie. Oh, my goodness. A big, fluffy pie with the most fantastic meringue, the most shimmering yellow custard, the perfect graham cracker crust. I was getting ready to procure slices of it for Mom and myself when Mom’s distress hit.

That’s sad,” Mom says. “You should have gotten some pie.”

“I know. Makes me sad, too.”

It’s dark out now. Our trek to home feels increasingly dangerous. People half dead, half alive, are lining the streets, some frail, some leaning giants, some stout dwarfs, all wearing rags, all peeling skin and losing digits. They want me. They want Mom’s stretcher. They want the oxygen. They are mad at me for not getting pie. I start walking faster, the stretcher bouncing on stones and uneven pavement, Mom’s head bouncing as well. I see a woman with a walker coming at us, shuffling fast, the feet of the walker scraping fast and frightful. She yells, “I know you stole that pie!”

I yell back at her. “I never got any pie!”

Mom is forgiving about the pie. These people are not.

About that powder room—the other elder, with daughter in attendance, emerged from the powder room and I was able to usher Mom in before calamity struck. But it was all very frantic. I had to get Mom out of the wheelchair and onto her feet so she could walk the few steps into the powder room. I had to grab the oxygen because she couldn’t be without it even for a bathroom visit. As soon as Mom was in the bathroom, she was frantic to lower herself on the toilet. I was frantic to get her pants down before she sat on that toilet. I was also trying to keep Mom’s oxygen tubing in her nostrils and trying to put the small oxygen tank down. We were twisted up with each other. Mom’s breaths were quick and raspy. My own breathing got raspy from the exertion and anxiety. I was almost as short of breath as Mom. I was sweating like crazy and having some of those damn chest pains. When Mom was finally on the toilet seat, letting out a gallon of urine, she worked on catching her breath. She held her face still as her nostrils flared and her shoulders moved up and down to help her draw in air. All of that took a while. When she felt better, she looked up at me and said, “You don’t look right.”

“Just tired. We’re gonna head home.”

“Yes, let’s go home.”

I don’t remember if I made any excuses before leaving. I probably did. A quick one: maybe I yelled to my brother, “Sorry, gotta get Mom home.” Something like that. I hope we hadn’t made a scene, caused hurt feelings. There I go again. Making apologies. Mom never made excuses or apologies. She survived hunger during the Depression, worked hard to go to nursing school, cared for polio patients, eventually ran the polio hospital set up by the community so that the children would not die in ambulances during long commutes to distant polio hospitals. Then she had six children. And her own child almost died of polio.

No, she didn’t apologize.

“I’m sorry,” Mom says.

“Huh?”

“I’m sorry. It’s my fault.”

This unsettles me. Now she actually is apologizing, and I don’t know what for.

“It’s not your fault, Mom. I made a bad decision. We’ll get home.”

“I should have said no to you. I was just trying to make you happy. You try so hard all the time. I didn’t want to go. I didn’t know this would happen.”

“Of course not.”

Is she crying?

But why wouldn’t she? This day is interminable, and we can’t find our way home.

I stop moving. Abruptly. Why am I out here with Mom’s head on a stretcher when I drove—in my car--to my brother’s house? And why am I pushing a stretcher when I’d brought Mom’s wheelchair to the party? And when, how, why did Mom’s body become just a head?

Wait a second.

Did I leave all of that behind? Did I leave the car, the wheelchair, and Mom’s body behind?

I start to maneuver the stretcher to turn it around. That’s not a simple thing to do with an old stretcher. “We need to go back,” I say. “I left a bunch of stuff behind.”

Mom shakes her head. Vigorously. I have to put my hand on her cheek to keep her head from rolling off the stretcher. “You did not leave a bunch of stuff behind,” she says.

“But where’s the car? The wheelchair? Where’s the rest of your body?”

“None of that matters.”

“Of course it does. Maybe I can find a way to call Gary. Or maybe reversing our tracks won’t take that long.” I say this, but it feels like I have been pushing this stretcher for weeks, months, years, decades even. I have pushed until we ended up downtown in the city of my origin, the city where Mom raised her brood of six. I have pushed until we are lost, tired and absurd.

But I need to get all that stuff I left behind. Mom needs her body. I stand—blank, frozen, mouth open. It’s all my fault, it’s all my fault, I mutter over and over.

“You can’t control this stuff,” Mom says.

“I was stupid. I should have said no to lunch.”

“Shit happens. Your brother nearly died of polio. Your WWII veteran father died of a massive heart attack after driving his son to work. I got pulmonary fibrosis even though I never smoked.”

I don’t like hearing this litany of Random. Random is an evil beast. We barricade against it with art, prayers, hopes. With stories. Could this be a story my dying brain is making? But it all of this feels very, very real.

“We got stuck in the powder room,” Mom says.

“Come on. Don’t be silly.”

“We are stuck in the powder room. They are still trying to get us out.”

I’d respond to that absurd statement, but I think I hear our crazy dog barking, crackling but muted, like a distorted Morse code message.

“Sam?” I call, looking around, turning a full circle. If that is Sam, we truly are almost home.

“I’d like another cookie,” Mom says.

I stop looking for Sam and I open the white bag. I find a cookie. I squint. Is that mold on the cookie? I close my eyes. When I open them, the cookie looks okay. But my hands are shaking, and bits of the cookie hit the ground as I direct it towards Mom’s mouth. She takes small bites of it.

“Do you hear Sammy?” I ask Mom.

“He’s not here. Not yet. Memorial Day weekend he’ll come.”

“Mom?”

“Yes.”

“I’m sorry I left your body at the party. And the wheelchair, and the car.”

“It’s fine. We will get home. Just keep moving.”

“But I was reckless.”

Then I think of something: my phone! I check my pockets, start tearing through the white supply bag, dumping its contents onto the sidewalk. If I can find my phone, then I can call my brother to help us.

“There are no phones here,” Mom says.

I keep patting my pockets and running my hand inside the white bag, but I know Mom is right. I don’t have a phone on me. I look hopefully at the people lining the streets, the ones half dead, half alive, the ones who want the lemon meringue pie.

“Don’t. Don’t leave me here and start asking those fools for phones. Everything is okay. We’ll get to Joyce Kilmer Avenue soon.”

“But why is it taking so long? Why don’t I have anything we need?”

“We have everything we need. Just keep moving. Keep moving until all the flotsam consumes itself. Then we’ll get home. Maybe there will be lemon meringue pie.”

“But I never got the pie.”

“Well, I think there will be pie.”