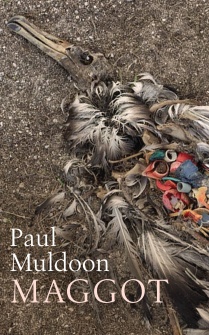

Worth Repeating: Maggot by Paul Muldoon

by Kelsey Osgood

The following review of the (then) forthcoming Maggot by Paul Muldoon was accepted by The Baltimore Review in 2010, prior to our re-launch, and is quoted at http://www.paulmuldoon.net/news.php4 . We think it's worth repeating. - Barbara Westwood Diehl, Senior Editor

Upon revisiting this review, I'm reminded –– somewhat unhappily –– of the hours I spent up in my hot attic room in Brooklyn first reading Maggot, then flitting back and forth between Maggot and my enormous, podium-supported OED, and then finally tapping a pencil against my forehead and thinking, "F*#& it, f*#& it" over and over again in a fatalistic refrain. Still, though, the lighter moments of my dalliance with Muldoon also come to mind: stumbling across a video of a Princeton University student interviewing Muldoon about the meter and lyrics to the Ke$ha song "Tik Tok" was a highlight, as was sitting quietly and sadly with my favorite poem in the collection, "A Sod Farm," a mesmerizing description of the mangled dermis of a burn victim. (While re-reading, I discovered that my new favorite, or perhaps a close second to my original, is "Ohrwurm," because who doesn't appreciate a poet who can pull off a reference to a "low-carb pork rind snack?") Perhaps the most amazing part of my whole Muldoon journey was when less than a year ago, I Googled myself (and yes, I am ashamed to admit this) and saw that PaulMuldoon.net was one of the results that came up. Intrigued, I clicked on it, and saw that Muldoon –– or whoever manages his website –– cited my piece in The Baltimore Review in the news and reviews section. I thought it hilarious that the Pulitzer Prize-winner, maybe unwittingly, had quoted the accolades of a little nothing like me –– what could that possibly do to help to his enormous reputation? Well, Muldoon, here's to hoping I did something for you, as you certainly did quite a bit for me.

Is there anything left to say of Paul Muldoon, he of the perfectly-disheveled poetry professor hair and Pulitzer Prize? What can one person, let alone a peon of the literary world, say of the very picture of the Portly, Bespectacled Savant, poetry editor of The New Yorker and author of eleven (eleven!) volumes of his own work? Is it possible that “there is little else to do but wonder and praise,” as Deryn Rees-Jones of The Independent wrote? Muldoon, the Northern Ireland-born, tenured Howard G. B. Clark Professor at Princeton University in New Jersey and author of the forthcoming Maggot (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, September 2010), has already been called everything from “a force of nature” to “the most dazzling poet of our time” to “detached and manipulative.” His prowess is about as legendary as a poet’s can be these days; he is “widely regarded as ‘difficult,’ even perverse,” according to Gregory Feeley of the Philadelphia Inquirer. “Difficult” is an adjective that seems to be universally applied to Muldoon, who incorporates into his work a swath of knowledge so grand and yet so singular it seems (and is) absurd to ask a reader to understand upfront. Over the course of one poem, he’ll jump from classical reference to personal anecdote to an allusion to Irish legend. To get the gist of “A Hare at Aldergrove,” for example, poem number six of thirty-nine in Maggot, one would need knowledge of airports in Northern Ireland, German aircrafts, ancient Celtic tribal leaders, IRA slogans past and present, tidbits from Muldoon’s own romantic past, and the basic filmography of Marilyn Monroe. His bathetic bouncing, enough to make even the toughest reader seasick, takes place within traditional poetic forms: epigrams, bastardized, elongated limericks, ekphrases, stanzas of quatrains, sestinas galore. All this combined with his tongue-twisting rhyming and sound-play can lead even the most diligent poetry connoisseur to voice some frustration. Peter Davison, himself a poet, penned a mostly favorable review of Muldoon’s 2002 prize-winning Moy Sand and Gravel for the New York Times, but he ends the write-up on a deflating note.

Is there anything left to say of Paul Muldoon, he of the perfectly-disheveled poetry professor hair and Pulitzer Prize? What can one person, let alone a peon of the literary world, say of the very picture of the Portly, Bespectacled Savant, poetry editor of The New Yorker and author of eleven (eleven!) volumes of his own work? Is it possible that “there is little else to do but wonder and praise,” as Deryn Rees-Jones of The Independent wrote? Muldoon, the Northern Ireland-born, tenured Howard G. B. Clark Professor at Princeton University in New Jersey and author of the forthcoming Maggot (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, September 2010), has already been called everything from “a force of nature” to “the most dazzling poet of our time” to “detached and manipulative.” His prowess is about as legendary as a poet’s can be these days; he is “widely regarded as ‘difficult,’ even perverse,” according to Gregory Feeley of the Philadelphia Inquirer. “Difficult” is an adjective that seems to be universally applied to Muldoon, who incorporates into his work a swath of knowledge so grand and yet so singular it seems (and is) absurd to ask a reader to understand upfront. Over the course of one poem, he’ll jump from classical reference to personal anecdote to an allusion to Irish legend. To get the gist of “A Hare at Aldergrove,” for example, poem number six of thirty-nine in Maggot, one would need knowledge of airports in Northern Ireland, German aircrafts, ancient Celtic tribal leaders, IRA slogans past and present, tidbits from Muldoon’s own romantic past, and the basic filmography of Marilyn Monroe. His bathetic bouncing, enough to make even the toughest reader seasick, takes place within traditional poetic forms: epigrams, bastardized, elongated limericks, ekphrases, stanzas of quatrains, sestinas galore. All this combined with his tongue-twisting rhyming and sound-play can lead even the most diligent poetry connoisseur to voice some frustration. Peter Davison, himself a poet, penned a mostly favorable review of Muldoon’s 2002 prize-winning Moy Sand and Gravel for the New York Times, but he ends the write-up on a deflating note.

“Muldoon is so varied and lavish a poet that no reader will find him wholly accessible, for while on one page he may speak simply of his dog or cat, on the next he'll spread his learning thickly upon slabs of bread baked in six different ovens. To be the carrier of such fancy equipment and complicated experience must create quandaries in the writer. He knows so much, has read so widely, feels so diversely, has traveled so broadly, that everything in his memory must lie helplessly alive and available, like turtles on their backs. Why not use every morsel? If the task of the poet, as Auden suggested, is ‘the clear expression of mixed feelings,’ Muldoon has fulfilled only the second half.”

Davison’s analysis of Muldoon’s work is tinged with resignation. He clearly views Muldoon’s mastery as more than a good deal manipulative and his work as the unavailable-for-purchase baked goods hot and steamy with historical meaning, all neatly stacked behind a counter guarded by a smirking cashier with no register. The counter-argument, voiced by quite a few, is that the poet (or any artist, for that matter) has no obligation to make his work coherent or palatable to lay people. “Times Are Difficult, So Why Should the Poetry Be Easy?” reads another New York Times headline about Muldoon. The issue here is the implied polarity of it all. Can one appreciate Muldoon’s work without knowing what a villanelle is? Is it worth it to read Maggot if you won’t really get it? Or perhaps it is possible to enjoy Muldoon’s work on a kind of spectrum of valuation, to recognize and appreciate his command of his talent without completely understanding it?

I myself read Maggot three times cover-to-cover in order to write this review, and the first time I did so I purposely avoided the dictionary, Wikipedia, Google, and any other resource that may have filled in one of the many, many holes for me. My classical education put me at a slight advantage over Average Joe Reader, who may not have harped on Penelope’s dream in The Odyssey his freshman year of college, as did the influence of the Irish nanny my family employed when I was a child. Had Carmel nee Heffernan not regaled me with bloody tales of political strife in Northern Ireland or begged me to read Angela’s Ashes when I was a wee bit too young, I might not have been able to pick out names of counties or zero in on the name “Cuchulainn,” the Celtic hound Frank McCourt so loves. But despite these pockets of knowledge, the reading was still a trying experience. By my count, there is only one poem that sits like a turtle on its back, ready and willing to be understood. This poem is “The Sod Farm,” and regardless of its basis, it’s accessible and mesmerizing on its own. (And also pretty icky, as it’s a meditation on the topography of the flesh of a burn victim. As the title of the volume would suggest, a lot of the poems here are focused on the moribund and on states of decay, though the carnality of it all is often lost beneath the all the bric-a-brac.)

What else is there to notice upon first read? Animals, and lots of them. Hummingbirds, porcupines and trout, oh my. The plethora of wildlife is first revered as a highbrow symbol and then quickly humiliated or slaughtered and reduced to its physical parts to be used in household clean-ups by reformed sluts (see: back-to-back ditties “Geese” and “More Geese.”) And then they are resurrected, alive and quick-footed, the subject of another ode. A badger whose signature white line leads straight to the “gamekeeper-turned-poacher.” A tit-for-tat comparison of a dolphin and a forensic entomologist. There is something of the eternal return swirling here, something about death and regeneration, but something not altogether lovely or Lion King or even that certain. The “iffy inevitably of it,” Muldoon says, in yet another poem (“Moryson’s Fancy”) that loops back and begins where it began.

Second and third readings are likely to produce linked associations so numerous one may feel compelled to diagram on one’s walls Bedlam-style in an attempt to get it all down. Complete understanding should not be the goal here, as Davison was correct in his assertion that the work will never fully be understood. Rather the ideal ambition is a deepening of one’s own knowledge and an opening to the idea that Muldoon’s work can serve as a catalyst for acquiring facts and stories irreverent, useless and profound all. From “Plan B,” for example, the first poem in this volume and one previously published in a collaborative work with photographer Norman McBeath, I learned the legend of Topsy, the elephant executed at Coney Island for killing three trainers in three years, and whose execution, which you can watch on YouTube, was filmed by Thomas Edison. From “Ohrwurm,” later in the collection, I gathered that “ohrwurm,” or in English “earworm,” is the technical term for a portion of music that gets stuck in one’s head, renamed by Oliver Sacks as Involuntary Musical Imagery, or INMI, which is not to be confused with the true musical hallucinations Sacks says can be crippling. “One of my patients,” the well-known neurologist writes in the journal Brain, “tiring of an endless megaphonic rendering of ‘O Come, All Ye Faithful’, tried to block this by playing a Chopin étude, only to find that four bars of the Chopin then iterated themselves in her mind non-stop for the next 24 h.” (1) Reading “Geese” with a little pluck, one learns from the first stanza that indeed, the feet of British geese were once tarred and sanded for the drive to market and that the festival of Bartholomew the Apostle, mentioned in the third stanza, is often celebrated by markets and fairs in late August. What’s the meaning of this connection? I simply haven’t gotten there yet.

Some mysteries shall remain, such as whether “trampled underfoot” was a direct nod to British rock group Led Zeppelin by the erstwhile librettist and guitar player Muldoon, or if Chazon Ish really was concerned with the etymology of “dork” (doubtful) but one thing is for sure: Maggot can (but doesn’t have to) be the portal into the wider world of Celtic folklore and the history of sideshows. It is an at-times gross and difficult challenge such as life, or in Muldoon’s words, a “shit storm/ through a bloody stream/ in which every morning the water again runs clear,” the clarity of which you ultimately control.

Kelsey Osgood blogs at itinerantdaughter.wordpress.com and has contributed to many publications online and in print including Self, New York Magazine and Bookslut. Her first book, LUCIDITY, will be published by the Overlook Press in Fall of 2013.