Review: Setting the Family Free

by Patricia Schultheis

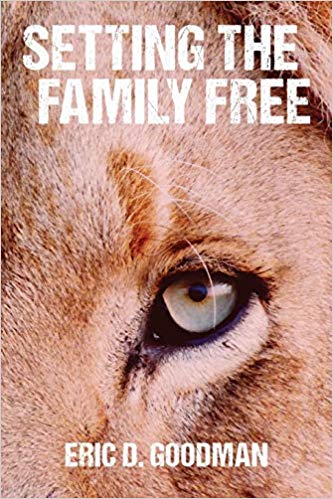

Setting the Family Free

Eric Goodman

Apprentice House Press, ISBN 9781627202169

193 pp. 2019

Setting the Family Free, by Baltimore writer Eric Goodman, is a riveting page-turner based on actual events. Eight years ago, a collector of exotic animals in Zanesville, Ohio, set his menagerie free before killing himself. Goodman moves his story 67 miles southwest, to Chillicothe and deftly overlays the  horrifying scenario of bears, panthers, tigers, and lions roaming among an unsuspecting populace with his characters’ plain-spoken Midwestern practicality. The resulting juxtaposition of a stolid American outlook with unfettered predation creates a tension that grips the reader to the very end.

horrifying scenario of bears, panthers, tigers, and lions roaming among an unsuspecting populace with his characters’ plain-spoken Midwestern practicality. The resulting juxtaposition of a stolid American outlook with unfettered predation creates a tension that grips the reader to the very end.

The story begins the afternoon eighty-two-year-old Bobby Anne Thompson looks out her kitchen window while emptying her dishwasher and notices her horses behaving oddly in their corral. But, ever the dutiful homemaker, Bobby Anne quickly returns to the task at hand. “A knife,” Goodman writes. “A fork. A teaspoon. A tiger.” And so begins a nightmare reaching from the backyards of peaceful Chillicothe to the concrete canyons of Columbus as the animals attack and, in turn, are hunted and destroyed.

Setting the Family Free is told from nearly twenty points of view, including those of the animals, a structure that keeps the plot moving but also prevents any character from becoming fully developed. This fragmentation is further complicated by Goodman’s interspersing brief chapters devoted to short comments from both major and minor characters such as Dr. Minnie Fields, professor of psychology at Shawnee State University; Mark Vernon, Chillicothe’s mayor; and Mike Skaggs, a drinking buddy of Sammy Johnson, the man whose purblind devotion to his animals ultimately destroys them as well as himself.

What emerges is a multifaceted impression of Sammy. To Mike Skaggs, he was a loner. To Chuck Ellison, Deputy in the Ross County Sheriff’s Department, he was a “selfish ass.” To Marielle, Sammy’s wife, he was a “gentle, loving man.” Through these snippets, Goodman reveals a disturbing truth about human relationships: none of us is the same person to two or more others. Just as each of us is unique, so each relationship between individuals is unique. In giving their impressions of Sammy, Goodman’s characters reveal those facets of themselves that responded to Sammy, but none answers the key question: What drove Sammy Johnson to collect wild animals? That answer Goodman wisely keeps to the one chapter told from Sammy’s point of view.

Sitting alone in the midst of his pride of lions, Sammy “sensed the world turning on him. Gun charges, jail time, back taxes, liens on the property, house arrest, the possibility of having his land taken away and auctioned off.” And worst of all, Marielle had left him. For the first time in his adult life, “He felt as though he’d lost control of his circumstances.” Without her moderating influence, Sammy’s self-proclaimed exceptionalism, knows no bounds—and he determines to wrest back control in a manner to make the world to take notice. “Sammy put the gun to his head. He knew the world would talk about him and his animals for years to come. . . . He looked at his animals and pulled the trigger.”

Sammy regarded his animals as “family,” but it was an unnatural family. Greater than his love for his animals was Sammy’s need for admiration. “He loved the way people regarded him as a master of wild animals that no one else could tame.” Sammy confused suppressing his animals’ predatory instincts with taming them, and once the animals were free, their instincts awakened. Perhaps the most tragic scene transpires when four lions become trapped outside a Columbus office tower. Spotting the tower’s jungle-like atrium, the lions leap toward it, only to hurl into a plate glass widow. Stunned, they’re easily shot by Chillicothe’s sheriff and his men.

Setting the Family Free is not without problems. The large cast of characters can be confusing, especially since many of them are not fully differentiated one from another. And the chapters told from the animals’ point of view are awkward at best. Nevertheless, it is engrossing read, and raises interesting questions about dominance, trust, instinct and love.

The opinions expressed in this review are solely those of Patricia Schultheis, the author of Baltimore's Lexington Market, St. Bart's Way, and A Balanced Life.