Local Author Spotlight: Patricia Schultheis

by Jacob Weber

Any beginning writer immediately comes face-to-face with two seemingly contradictory truths about writing. First, almost anything can be grist for a good story, no matter how mundane or commonplace it might seem. Secondly—and here's the seemingly contradictory part—just because something seems interesting to you doesn't mean it will be interesting to others. As my adviser in my writing program told me often, "You might think it's a big deal that Grandma died. But everyone's grandmother dies, and just because it matters to you doesn't mean it will matter to others." Even an ordinary life has plenty of material for a good story, but the raw materials alone won't be enough. You need to find something that will make the story as interesting to others as it is to you.

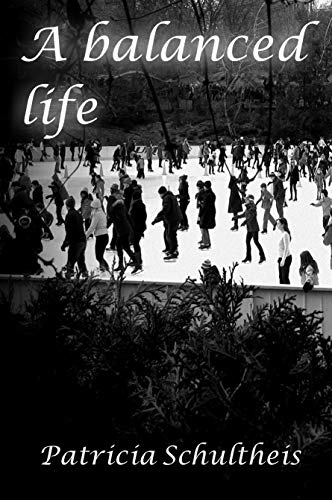

Patricia Schultheis accomplishes this in her new memoir A Balanced Life in two ways. First is her use of skating as an image to knit together all the phases of her life. Early on, she calls the memoir a "book about skating," which is, in a sense, a lie, because it's a memoir of a Polish-American, Catholic girl from Connecticut who  grew up, moved to Baltimore, raised a family with a history teacher, and became a writer late in life. But on another level, she's completely correct, because it's skating that keeps the book from being a boring "grandma died" story full of reminiscences interesting only to the writer. Skating animates the raw materials of Schultheis's life, making it as alive to the reader as it was to her. From the moment her clumsy uncle brings her a pair of used skates over the objections of her fastidious mother, skating becomes a poetic image in the book that gives it the drive of fiction.

grew up, moved to Baltimore, raised a family with a history teacher, and became a writer late in life. But on another level, she's completely correct, because it's skating that keeps the book from being a boring "grandma died" story full of reminiscences interesting only to the writer. Skating animates the raw materials of Schultheis's life, making it as alive to the reader as it was to her. From the moment her clumsy uncle brings her a pair of used skates over the objections of her fastidious mother, skating becomes a poetic image in the book that gives it the drive of fiction.

Schultheis took to skating, although she was never competition-level-good. Polio in her younger years that made one leg shorter than the other saw to that. Her unbalanced legs made her awkward, such that the "balance" in A Balanced Life was trickier for her than for most people. But she kept at it. Like writing, it was something she only took to seriously later in life. Maybe reflective of the author's life, the second half of the book is probably more compelling than the first, picking up as Schultheis got surer and surer of her footing.

The second reason A Balanced Life managed to avoid the dullness trap was the author's keen sense of history. Her first book, St. Bart's Way, already revealed her understanding of how history shapes the world around us now, especially at the local level. It's not surprising that the author immediately fell in love with her history teacher husband, a man for whom history was "immediate and palpable." Bill saw history as "a story whose plot is unfolding all around us all the time. The railroad five blocks from my apartment resulted in this. And after Baltimore's central core burned in 1904, the city expanded here. And Woodrow Wilson taught at Johns Hopkins when."

Although this is a memoir and not fiction, the same sense of specificity coming from history at the local level pervades A Balanced Life as St. Bart's Way. Schultheis isn't just telling about her life. She is using herself as a historical figure she has researched thoroughly. Her life is a touch point for history, a history in which the global and the national come home at the local level. She is able, for example, to put her own troubles figuring out romance as a young woman into a larger context:

"Worse, it is the late 1950's, an era of muscular sexuality and teasing flirtation. Every song on the radio promises Johnny Romance and every ad is a valentine, one frequently featuring ice skaters. A redhead whose skirt flips up to sell Lucky Strikes, a male skater who pushes his beloved in a sled across the ice while urging us to buy Omega watches. In the '50s, between every popular girl's breasts hangs a boy's high school ring. That means she is going steady. And that means she will soon be going to the Chapel of Love. Where she goes after that doesn't matter."

Reading A Balanced Life is a lot like the feeling I got talking to my parents about their lives after I'd just watched Mad Men. Suddenly, their ordinary lives seemed much more interesting to me, because I'd just seen a brilliant contextualizing of the ordinary, making its relevance to the grand, sweeping scope of history clearer. Schultheis's memoir not only makes an ordinary life seem more extraordinary, it makes far-off and remote "big" history seem as close as the bus stop on the next street.