Instrumental Notes from Writers in Bands

by Holly Morse-Ellington

Edgar Allen Poe’s cask of poems and stories has inspired musicians from the classical strings to the punk screams. From André Caplet's Conte fantastique and Rachmaninoff's choral symphony The Bells, to Bob Dylan's "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues," to Queen’s "Nevermore" written by Freddie Mercury, to Iron Maiden, Stevie Nicks, The White Stripes, Lou Reed’s double CD album The Raven, and on and on evermore—Poe’s words thump off the page to beat in the ear.

I turned tables and asked writer-musicians how music has inspired their prose. I’ll be speaking with Gerard "Gerry" LaFemina, Associate Professor of English and Director, Frostburg Center for Literary Arts, and Jason Tinney, author of Ripple Meets the Deep, on the panel “Music As Muse” at the 9th Annual Independent Lit Festival in Frostburg. Here’s a discussion that scratches the surface of programming and presenters to hear from. (And of course The Baltimore Review will be there with its tell-tale stories.)

Do you listen to music while you're writing, or do you need silence?

GLF: I listen to music when I’m writing all the time—though I also write in crowded places, with the TV on sometimes. I like a potential for distraction, it keeps the imagination open in some ways. Music, in particular, helps generate rhythms and momentum when I’m composing.

JT: It seems to go in cycles. There was a time when I couldn’t write without having music in the background. Then I got to a point where music was a distraction. But lately, I’ve gone back to writing with music. It depends on the mood, I suppose. Sometimes the silence can be overwhelming and you get stuck. Throwing on some Sam Cooke can relieve the tension so you can keep typing.

Do you tailor a playlist or vary the genre of music you listen to depending on the mood and subject of a particular writing project?

GLF: Not at all. I listen to whatever I’m in the mood for. I rarely make playlists—I still am old school in that regard. I spin vinyl. For my novel, Clamor, I made a playlist for the novel that functioned as a kind of soundtrack while reading it.

JT: No, but if you are writing about broken relationships, Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks is good to have on hand.

What are some songs and lyrics that have inspired your characters or plot lines?

GLF: I grew up on the New York hardcore scene and so punk/alternative/hardcore music has appeared in a variety of my poems and stories. One poem, titled “New York Hardcore,” attempts to feel like a hardcore song (short, sonically aggressive, with lots of quick rhyme). David Bowie’s “Heroes,” the Clash’s “London Calling” have all appeared in poems. I’m interested in the nexus of the literary and music. So I’ve also co-edited an anthology of poets covering the album London Calling and am now working on one of poets covering the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds.

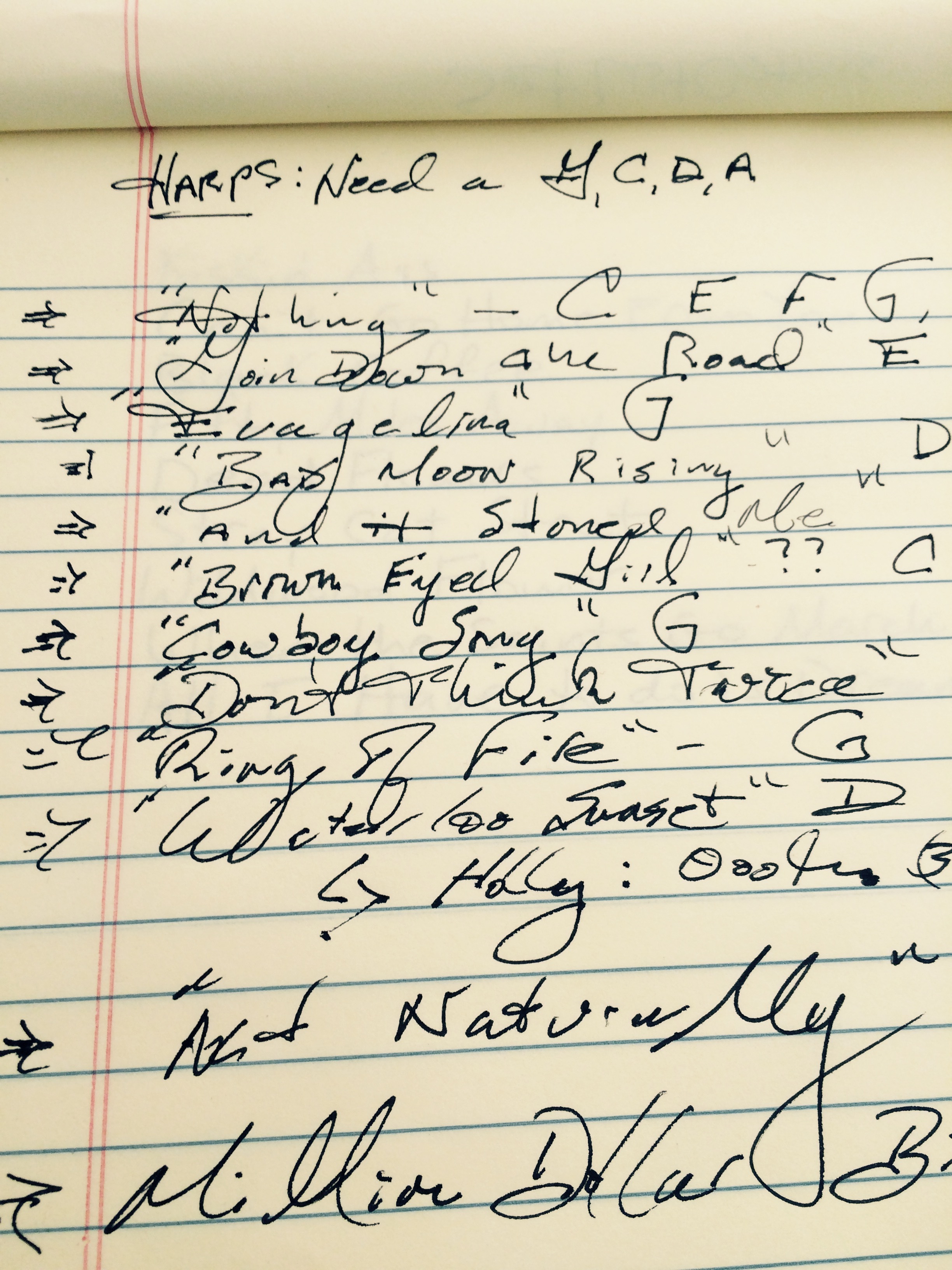

JT: In my collection of short stories, Ripple Meets the Deep, there are ten pieces that follow a harmonica player on tour in up-state New York. The series takes its title from the blues song, “Make Me a Pallet Down on Your Floor,” and each individual story, according to the situation, has a subtitle that is the title of a country, blues, or folk song. For example, one story is titled, “Make Me a Pallet: St. James Infirmary” and it concerns the characters who show up in the morning at the breakfast lounge at a La Quinta.

How does the music itself, the melody and chords, influence either what you write about or the style in which you write?

GLF: I think it’s more having grown up in a particular musical culture that has done that rather than any particular songs or records while writing. I’m much more a writer interested in people and their motivations. People’s musical tastes are one way that we get a glimpse of who they are as people. That said, my early work was often referred to as being “musically aggressive” which I think came from my punk days. Jim Daniels once called me “The Iggy Pop of American Poetry.”

JT: Another story from Ripple is “Make Me a Pallet: Shave ‘em Dry,” which I took from the Lucille Bogan song from the 1930s. It’s not sexually charged—it is. She goes for the throat, singing that she could “make a dead man come.” I wanted to write a story that harnessed that ferocity in narrative with a blues feel. Two people rolling around in a hotel room. My version of “Shave ‘em Dry” is timid compared to Lucille’s, but I did take it as a huge compliment when another writer called it “geographic porn.”

What are some stylistic ways you incorporate musicality into the language of your writing?

GLF: Mostly I think it’s in the rhythm of my lines and my attention to sound interaction. I read everything out loud. Over and over again.

JT: I’ve always done this stomping thing when reading over drafts—stomping my foot down to find the rhythm of words within the sentence. I also apply the Dylan-Litmus Test: Reading a story aloud in Bob Dylan’s voice. If Dylan can’t read it, who else would?

Many famous songs have been inspired by novels and short stories. What is your favorite music-from-story offshoot?

GLF: “Night Train to Lorca” by the Pogues. It’s so strange.

JT: “Dixieland” by Steve Earle. It’s a song that centers around an Irishman named Kilrain fighting for the Union during the Civil War. The character comes from Michael Shaara’s Pulitzer-winning novel The Killer Angels.

What band or singer-songwriter would you most like to have write a song based on one of your published works? (And, why would this musician be a good fit for your publication?)

GLF: Oh, I would love to have somebody like Bowie do that, or Joe Jackson, who shares a love for New York. More likely though, it should be Jesse Malin who is a delightfully literary songwriter and who comes from the same scene.

JT: Of the songwriters I’ve mentioned—Blood on the Tracks really is a short story collection. James McMurtry, son of Larry, writes fantastic short stories in song—Lucinda Williams, Guy Clark and many others are masters of the song as a short story. I’d be honored to have any of these folks adapt one of my stories into a song. If he were still alive, I’d be incredibly humbled if Thelonias Monk took something I’d written and turned it into an instrumental jazz piece.

Comment on your thoughts about music as a way of keeping the literary arts relevant and accessible in today's society.

GLF: Song lyrics are some of the first memorized language kids have—usually because the words “mean something” to them. Pop music is a notoriously young art, though, and I think it can be a doorway to find literature—words—that really matter in our adult life.

JT: I think music and literature go hand in hand. I’m fortunate that I perform music and also write literature and I love that the two forms can overlap. Both are about telling stories.