Hello Padura: A Review of Adíos Hemingway

by Holly Morse-Ellington

Adíos Hemingway

by Leonardo Padura Fuentes

Grove Press

pp. #229

ISBN: 978-1-84195-795-1

Release: 2005

Genre: Novel

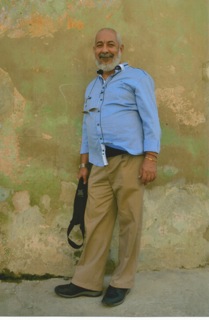

Baltimore Review editor Holly Morse-Ellington was unfamiliar with the Cuban author Leonardo Padura until she traveled to Havana for a creative nonfiction workshop with Lee Gutkind. As part of their writing retreat, Holly and the other workshop attendees had the opportunity to sit down with Padura over lunch and ask him about his writing life. While Padura’s fame is growing among Americans for his screenplay for Four Seasons in Havana, a 2016 Netflix series based on his detective novels, Padura is not new to international literary acclaim. He was awarded the National Prize for Literature in 2012 and the Iberoamerican Nobel Prize in 2015.

With wife Miss Mary out of the country, Hemingway is left to his own vices—drinking Chianti and securing the grounds of his Cuban estate while armed with a fully loaded Thompson machine gun. No, Ernest Hemingway’s property, Finca Vigía, is not under attack by a band of revolutionaries in this fictional recreation of the author’s restless last night at his island home. Instead, Hemingway is attacked by forces he can’t hold off any further: age, illness, and depression. In Adíos Hemingway author Leonardo Padura brings Inspector Conde out of retirement to investigate a case that resonates with the detective turned aspiring writer. Cuban police have discovered human bone fragments pocked with the trajectory of two bullets at present day Finca Vigía, implicating Papa Hemingway in, at best, a decades-old criminal cover-up, or at worst, murder.

Adíos Hemingway alternates between Ernest Hemingway’s point of view on the night in question, October 2, 1958, and Mario Conde’s present day point of view as he resolves to crack the case. Hemingway has been deceased for over forty years when a severe storm ravages Finca Vigía and uproots a tree that had heretofore concealed the remains of a Caucasian male. “The first thing [Conde] saw were the roots of the upturned mango tree. They were like the skeins of Medusa’s hair, straggly and aggressive, appealing to the distant sky from where death had descended, and through which another death had been revealed.”

Unlike the Cuban police who have bigger fish to catch, Conde takes an interest in the case to serve and protect Hemingway’s legacy. But living up to his reputation as ace detective, Conde works the alternate theory that the truth will not set Hemingway free: “…and now, in the midst of so many things bought, hunted and given to their owner, a man whose envy had seemed capable of destroying all the writers in the world, [Conde] concluded that he would be happy to find a trail leading him to Hemingway’s guilt: it would suit him quite well if he turned out to be a common murderer.” Not a trace of evidence slips past Inspector Conde. Not even the seemingly red herring that is Hemingway’s most prized trophy—Ava Gardner’s lacy black knickers. At times both Hemingway and Conde—and even Padura—mentally wander off from their respective tasks by reconstructing the scene of Miss Gardner skinny-dipping in Hemingway’s pool. But what would a detective novel with the heat-packing, big game-hunting suspect that is Hemingway be without a femme fatale?

In his author’s note the Cuban novelist discusses taking creative license with facts to center a story around Hemingway, a writer with whom Padura confesses to having a “fierce love-hate relationship.” Angling for the right words to present a likeness of the literary big fish that is Hemingway is an endeavor that requires finesse and patience. Padura skillfully strikes a balance by arousing equal parts empathy and disgust, pitting the reader in an irresistible tug-of-war between wanting to root for a Hemingway hero while also suspecting he could be a scoundrel deserving of a strong slap on the wrist.

While the character Hemingway is not completely alone throughout this fateful evening (which accounts for additional suspects), he journeys down a lonely road shadowed by “proud and noble trees . . . like faithful friends,” well-appointed catalysts for the darkness of guilt for scorned writers and wives that looms in his mind. His only real companion is his pet, Black Dog. Padura evokes a haunted man wandering the thicket of branches, talking to himself and Black Dog who “mirror(s) the step of his master, without barking or moving away towards the trees.” That is until his friend, sensing an unwanted presence, barks and is commanded, “Heel, Black Dog . . . that’s enough for today.” One cannot shake the feeling that Padura crafts a chilling parallel between shushing the pet’s warning cries and silencing the character’s inner Black Dog of mental demons.

It is through Conde’s internal conflict between awe and irreverence towards Hemingway’s work and personal belongings that Padura opens a window for the reader to view the man of mystery more intimately. “Conde committed the ultimate act of sacrilege: he took off his own shoes and put on the writer’s old moccasins, which were several sizes too big for him.” Big shoes to fill indeed.

Padura is a good fit to explore what went on in the mind and daily goings-on of Hemingway, a man who chose to live in Cuba for two decades and arguably befriended the fishermen in nearby Cojímar. Right or wrong, Hemingway is rooted in Cuban culture more firmly than the upended mango tree in Adíos Hemingway. In a 2017 interview in Havana with American writers, Padura is asked if he considers leaving Cuba like other Cuban artists have once they’ve reached his level of success. Padura states that Cuba is not only home but also integral to his work. “The memory of a writer,” he says, “to belong to a place and to a culture is very important.”

Padura continues to say that he created his recurring protagonist, Detective Conde, as a novelist’s way “to try to make a chronicle of Cuban life.” Padura adds, “The dead body is not important. [What is] important is the atmosphere….More or less, this is my way.”

And in Padura’s way, the identity of the bones in Adíos Hemingway are irrelevant. It’s Padura’s ability to imagine and extract the deeper emotions a character buries under his ego that makes this novel as compelling to read as solving the crime.

#

A review of Adíos Hemingway (2005) by Leonardo Padura Fuentes, translated from Spanish by John King. Included are notes from a conversation with author Padura on February 2, 2017 in Havana, Cuba at Fototeca de Cuba and continued at the restaurant, El Zaguán.

Holly Morse-Ellington is an essayist and playwright whose works have been published in Broad River Review, Baltimore Style, and Baltimore’s City Paper, among others. She recently returned from Cuba where she participated in Lee Gutkind’s creative nonfiction workshop, “Bringing Havana to Life.” Holly is also an editor for The Baltimore Review. www.hollyneat.com