A Kraków Literary Journal: Notes on The Year of Lem

by Michael Downs

To call Stanisław Lem a science fiction writer is to define him too narrowly, but “science fiction writer” is what he is most often called. The shame is that he spent a literary lifetime redefining the possibilities and limits of humanity and technology. “Wcale nie chcemy zdobywać kosmosu, chcemy tylko roszeryć Ziemię do jego granic” reads a quotation from his work, displayed over two stories of a building here in Kraków. In my translation:

“We don’t at all want to conquer space, we only want to extend the Earth to its limits.”

***

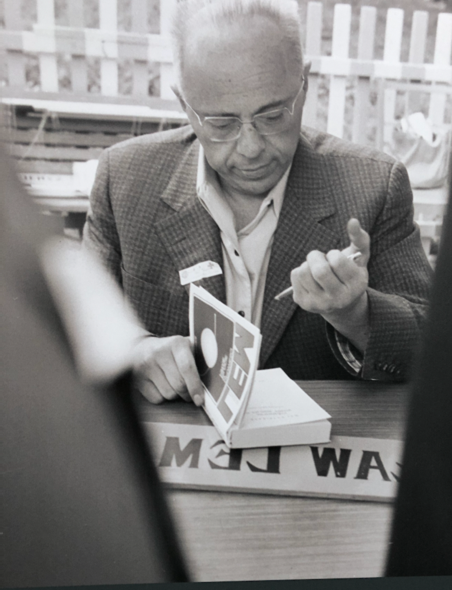

He was born in 1921, which is why Poland’s highest legislative body declared 2021 to be The Year of Lem. Evidence of that celebration popped up all over here in Kraków, where Lem lived most of his life. There was a festival. Posters in bookstore windows. A display outside a shopping mall that presented dozens of his book covers, including his most famous work, the novel Solaris. A theater even presented a play, Lem vs. P.K. Dick, which depicted Lem in conversation by telephone with Philip K. Dick, who authored The Man in the High Castle and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which became the movie Blade Runner. Dick also famously sent a manifesto to the FBI claiming that the author known as “Stanisław Lem” was in reality a cadre of KGB agents writing under that name and subtly promoting Soviet propaganda through science fiction.

Dick’s argument? No single person could write such varied work as did this Lem. Dick, at the time, was known to be drug-addled and paranoid, and nothing came of his denunciation.

***

Lem did write a lot and with variety. He wrote more than a dozen novels. He wrote poetry. He wrote essays of a philosophical bent regarding science and technology. His work has been translated into 40 languages with more than 30 million copies sold, more than any other Polish writer. For decades, he’s been a chief Polish export.

***

Here in Kraków, I’m working as part of the U.S. Fulbright cultural exchange program, which I first learned of some thirty years ago when I lived in a rooming house in Tucson, Arizona. That’s when I met Gernot, a Fulbright researcher from Germany. Gernot loved Lem. He demanded I read Solaris. Likely, Gernot had read the German translation. Mine was in English. To this day, I recall nothing about reading it. Sci-fi wasn’t my bag, and especially not the sort of sci-fi I found in Solaris. The detail seemed endless and not always purposeful: this breathing hose, that biconvex window, this complex reference to a scientific study that didn’t really exist. All that world-building.

But years later, I realize my trouble might also have been that the English translation was bad. Lem, who was said to read English fluently, despised that translation of Solaris, and no wonder. The people who made it based their work on a French-language version, not the original Lem prose. It’s as if Lem told a story to a Frenchman who told the story to a couple of Brits who then told the story to me. Imagine the fractures.

***

“Ignoramus et ignorabimus: We do not know and will not know.” These lines from Solaris come from a more recent translation, made by Bill Johnston, one of the top translators of Polish literature into English. Lem’s family, apparently, approves of Johnston’s translation, though it is only available digitally or via audio book and not in hardcover or paperback because of old copyrights.

***

“We do not know and will not know.” One could argue that this is the whole point of Solaris, in which a few humans in a space station orbit a distant planet where the only living thing is a gelatinous ocean, which communicates by drawing from the humans their deepest, most shameful and intimate histories and then making them corporeal, to be relived.

There are limits to what we can know about any other being, Lem tells us, across languages but even within the same language. We will fail to understand each other. “How can you communicate with the ocean if you can’t communicate with each other?” a character in Solaris asks. So we must remember that our perceptions of other people, other places, other things, are always in some way in error, made faulty by our own limitations. Across languages, even a great science fiction novel can seem forgettable to a reader unpracticed with a particular sort of Polish sci-fi.

The other day here in Poland, I tried to order a large cappuccino for my wife and an Americano for me, but what the server brought to our table was a large cappuccino and what looked to be another smaller one. I pointed and asked, “Americano?” and the server nodded, yes, “tak.” She was harried, I could see, a birthday party took up two nearby tables, and her English seemed at about the same level as my Polish, so I chose to enjoy whatever coffee she’d brought.

Trivial, yes, but illustrative. We were a gelatinous ocean and a human researcher on a space station leagues away, not knowing and never to know.

***

In 2019, some thirteen years after Lem’s death in 2006, a Polish website published the English translation of a recently discovered Lem story in which a robot is hunted for sport. The story elicited much excitement in Lem World. It was the first new piece of Lem writing to appear in decades, a great and rare surprise. The author, apparently, burned whatever of his writing he disliked. So how did this story survive among his papers yet not find publication? Theories included this: that the story too closely mirrored Lem’s experience of World War II and the Holocaust. Throughout his life, Lem worked to conceal many aspects of that past, which found him a 20-year-old Jewish man when the Germans arrived in his home city of Lwów. To publish this robot tale, which suggests aspects of the Holocaust, might have pointed too closely to Lem’s past for his comfort.

Agnieska Gajewska, a Polish literary scholar, revealed Lem’s World War II history in her book Holocaust and the Stars: The Past in the Prose of Stanisław Lem (English translation, Routledge, 2021; first published in Poland, 2016). To write the book, she researched and discovered horrific facts of Lem’s life that he seldom if ever revealed. Then she searched his work for those horrors in disguise, finding many.

When the new Lem story appeared, analogies to the Holocaust seemed apparent. The robot fleeing from human hunters, for example, wonders why he does not fall into despair, why any robot in this situation wouldn’t “let himself be shot in the back, or let his head be smashed, without the bother of this effort to escape, as desperate as it was helpless?”

***

Sen. J. William Fulbright of Arkansas proposed the program that bears his name in the aftermath of World War II. He did not know Lem. He didn’t know, as Gajewska revealed years later, that Lem had been forced to clear dead bodies from a prison, that he’d nearly been executed and was spared only by the arrival of a German film company that distracted the soldiers, that his entire extended family died in German camps or in the post-war pogrom in Kielce, Poland.

Fulbright did not know Lem, but he knew many such stories. His exchange program grew out of his belief that culture and empathy might prevent such horrors from ever happening again. In a memoir titled “Seeing the World as Others See It,” published in 1989, Fulbright explained his thinking.

The program’s “essential aim,” he wrote, “is to encourage people in all countries, and especially their political leaders, to stop denying others the right to their own view of reality ... The exchange program is not a panacea but an avenue of hope–possibly our best hope and conceivably our only hope–for the survival and further progress of humanity.”

Moreover, he wrote, he hoped that people meeting across borders, across languages, could foster “empathy–the ability to see the world as others see it, and to allow for the possibility that others may see something that we have failed to see, or may see it more accurately.”

Gernot, the Fulbright from Germany, thought Solaris was a work of genius. I did not. He saw it more accurately. To engage as Fulbrights engage is to become practiced in miscommunication, I am learning. Like a human in orbit over a planet inhabited by a gelatinous ocean, I am learning what I do not know and what I may never know. Over and again, I’m witness to my ignorance and limitations. This is an experience in empathy but not because my humanity is so expansive that I can intuit the plights of others. No, this is empathy only because it begins as an experience in humility.

***

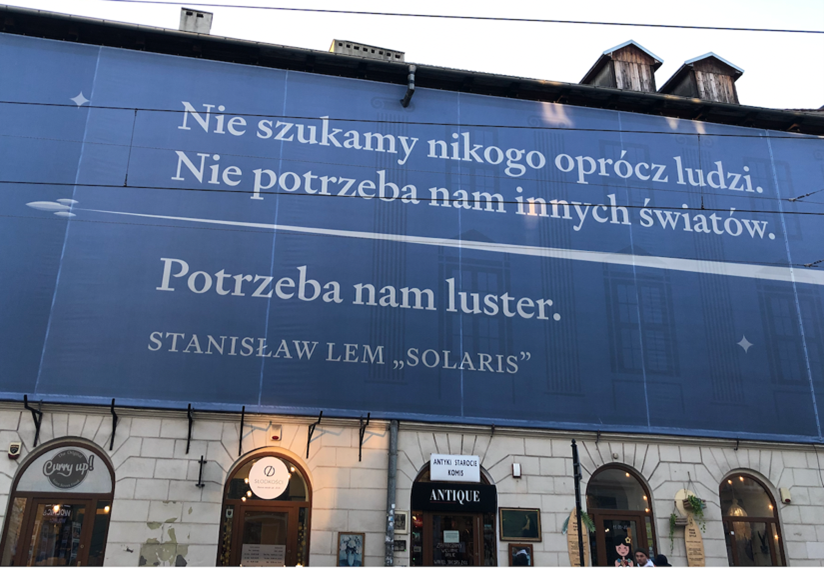

Also two-stories high and on display during the Year of Lem was this oft-repeated quotation from Solaris: “Nie szukamy nikogo oprócz ludzi. Nie potrzeba nam innych światów. Potrzeba nam luster.”

Which, in Bill Johnston’s translation, reads, “We’re not searching for anything except people. We don’t need other worlds. We need mirrors.”

To read more about Lem and Dick, click here.

To read Lem’s story about the robot hunted by humans, in English, click here.

To read more about Lem and the Holocaust, click here.

Michael Downs, who serves on the board of Baltimore Review, will spend the next several months living and writing in Kraków as a U.S. Fulbright Scholar. He will periodically write here on the BR blog regarding literary Kraków. He’s the author, most recently, of the novel The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist. Learn more about him at michael-downs.net.