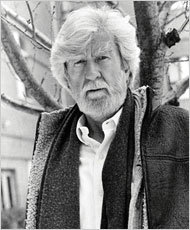

A Conversation with Maryland Poet Laureate Stanley Plumly

by Kathleen Hellen

The interview was conducted on December 4, 2009, prior to the publication of his collection, Orphan Hours. The interview originally appeared in the Summer/Fall 2010 issue of The Baltimore Review.

KH:

Can you talk about what you call the “abrupt edge”?

SP:

The abrupt edge is actually an ornithological term that I have turned into a metaphor . . . It’s that area of greatest interest and intensity— for birds, of course, but I think also as a metaphor— between the dangerous open space and the bower or covered safe place, let’s say the woods as opposed to an open field—where the danger is, where anything can happen. If [ I ] can find a sense of the experience where there is both danger and safety—and maybe the safety part is the form— then I think I’ve got it right. The danger, of course, would be in the content.

KH:

When you say “danger,” are you talking about going into those experiences that are emotionally charged?

SP:

Absolutely. I think some people would use the word “risk”; I don’t like that so much. Danger, and at the same time excitement. And it has to be that. Otherwise, you’re just filling out the form.

KH:

What part does the speaker of the poem play in that danger?

SP:

The speakers in my poems are both direct participants and observers of themselves—bifurcated or binary, if you will. They’re in two places at once. They’re having the experience and narrating the experience. That’s a tension in itself . . . But the part of the speaker narrating the experience has to be believable.

KH:

Does the speaker regulate the emotion of the poem?

SP:

Discovers it, is how I would put it. My experience in writing and rewriting—which is mostly what writing is—is that you’re in the process of constantly discovering. And it doesn’t end until you’re absolutely sure this is as far as you can go in that poem. And it may be months and months and months of just changing a word or two, until you’re really, finally get there.

Just this morning I changed a couple words in a poem. I took out a phrase, which caused me to re-lineate that part of the poem, and it changed it. I think it’s truer now than it was before. More authentic—all those clichés we use when talking about poetry. It’s a more fulfilled experience. It’s a richer and truer event than it was before . . .

KH:

When you say “truer,” what do you mean?

SP:

We like to think of it as truer to the experience, which is the past. I don’t think so. I think truer to the future, to where the poem is headed . . . what its destiny really was. When you get to the point Yeats called the closing of the box, when you hear the click, you know it’s done. It’s arrived at the place it was meant to be . . . You sense that. It becomes as good as it will ever be, as it will ever get.

I suppose twenty-five years from now, looking back on a particular poem I’ll say, it didn’t get there. And I’ve done that with a poem that’s twenty years old . . .You change as a writer, not just more skilled but larger . . . You see the capacity and greater possibility of a piece of work . . . Every time you write a poem, you’re starting all over, probably better and wiser and more knowledgeable than you were before. But that doesn’t happen fast, either. That may take a while.

KH:

Memory plays a large part in your personal aesthetic. Can you talk about that?

SP:

Mnemosyne is the goddess of poetry, and she’s the goddess of memory. I often say that lyric poetry is made up of two essential presences: Memory and the moment. And what is the moment? The moment is the moment you’re writing the poem—what you’re feeling, what you’re in touch with. And part of what you’re in touch with is that emotional past, is that event in the past, or is that example from the past. I don’t think I write so much about the past as I . . . introduce the past into the moment of my contemplation.

KH:

Is that “emotion recollected in tranquility”?

SP:

It’s more emotion recollected in anxiety. Part of that anxiety is: Am I doing it right? Does it feel true? . . . You can fool yourself into believing all kinds of stuff at that time . . . You want to get on with it . . . More often than not, the real “recollected in tranquility” comes when you’re going back to rewriting. I think Wordsworth’s perception is more about rewriting, recasting, than writing itself.

KH:

You have a painter’s eye in your poems. Objects seem to come out of the darkness to be illuminated in the poem. Can you talk about where that comes from?

SP:

It comes from my love of art, for one thing . . . Poems are not just aural experiences. They’re visual experiences as well. You can’t separate the two. Line breaks and all we talk about, especially in free verse, are visual as much as vocal.

KH:

You’ve said free verse should be a genre in itself?

SP:

Not quite that. It’s become synonymous with lyrical, I think. When you see a poem of a more . . . announced formal nature—rhyme, meter, whatever—however varying and interestingly it’s done, it stands out because it’s anomalous . . .

It’s hard to talk about free verse. It’s only been in the last ten to twenty years we’ve really begun to understand it has a prosody, too, and one can talk about it in a formal sense . . . What makes it difficult is that free verse forms tend to be very idiosyncratic, one to another . . . as opposed to sonnets, as the most egregious and obvious example. My notion has always been, when I talk about this issue with students, is that even the sonnet form—take Shakespeare’s sonnets, take Number 18 compared to a later sonnet, 73—they’re different poems, even though they’re the same form. Totally different rhythms. Although the structure in the most overt sense is identical, from a textural point of view, in terms of image and syntax, totally different. And yet they’re both so-called English sonnets.

KH:

I don’t hear a distinction between lyric and narrative poetry in what you’re saying.

SP:

I don’t think there is such a thing . . . But if it completely depends on [narrative], it becomes a kind of whining . . . for therapeutic purposes . . . There has to be distance, and the trouble with narrative is it closes that distance. It becomes sentimental, if it’s only that. Like all poems, free verse is not different in that way. There’s a constant tension between the lyricism and the so-called story. The word “verse” in the ancient languages means to return, to repeat, as in meter and rhyme and so forth—motif even.

All poetry is a mixture of poetry and prose. Wordsworth says that. It needs to go on, continue. It’s the energy. And that’s the story part. I say to students, we think of poetry as a horizontal medium because of the lines; but it’s not. It’s vertical. It’s an up and down form. And the bottom of the poem weighs more than the top. That’s where the gravity is; it pulls the poem down. And all poems move in that direction. They get darker, they get deeper, they get heavier as they go on. They accumulate.

KH:

Speaking of accumulation, there’s an aspect of your style—both in the poetry and prose—that depends on accretion. You write with appositives, absolute phrases that accumulate.

SP:

It’s in the nature of my process . . . It’s in Keats, too—that idea. You want to extend as long as possible, hold the moment of contemplation, the moment of the voice, of the music, as long as possible, in a certain rhythm.

Now at what point does that break down? You hear that, and you don’t want to extend it . . . I type my poems . . . I find in typing, that activity, I’m hearing the words better . . . So, you’re right. There is that additive sense involved. I think it deepens the texture, it enriches the mixture—all of that. Absolutely. It all has to do with extending, extending, as much as possible.

KH:

It’s an extension of the ecstatic moment?

SP:

If you can get that. But you can’t start that way . . . it builds toward that. I feel the poem begin quietly and end even more quietly.

KH:

You’ve talked about the generational differences in poetry. Will you talk a little bit about that now?

SP:

It’s in the nature of things. As a teacher of the art, I see that in my own students all the time. I’ve had hundreds of poets, and many, many of them are very successful. Some are close to my own age; some are sixty, some are in their fifties, and I can see how they have changed over time . . . I can see what their expectations are and the differences. And that’s sometimes an issue, because you have to be flexible, bendable, to accommodate a world they’ve grown up in, a language they’ve grown up with, attitudes—the way the art itself has changed over time—that you are on the far side of, that they are immersed completely in. Most of my students have gone through a phase of reading and admiring Language poets. That came along long after I had matured in the art and basically rejected. They didn’t. They learn from it.

That’s such a nebulous subject anyway. What is Language poetry? And who are the Language poets? As far as I’m concerned, [John] Ashbery is not a Language poet. Jorie Graham is not a Language poet . . . Charles Berstein is. A poet like Keith Waldrop is. But you can learn from them as well, I think.

KH:

Can you speak to your point about how the autobiographical in a poem needs to be archetypal?

SP:

The real autobiography is the autobiography of the imagination. But what is the imagination? Imagination is like metaphor . . . You cannot make it up. You can only make it from. And you’ve got to be clear what you’re making it from. That’s part of the discovery, too. It starts with the littlest thing.

I have a long poem [called “Lost Key”] that’s in the recent [American Poetry Review]. It’s thirteen lines to the stanza and it’s thirteen stanzas . . . It’s a mailbox key . . . the size of a penny or a fingernail. How on earth did I get that much material out of that? On the literal side, I was quite a bit upset. It had something to do with the size of the key . . . And from a symbolic point of view it was a mailbox key—that’s a currency with the world.

I carried it around for awhile. And I heard a little piece of music that I knew but I had forgotten about. That’s Beethoven’s little piano piece called “Rage over a lost penny.” That’s it! It gave me permission to have rage . . . and that carried me through a whole history of material from the past.

KH:

That synchronicity is interesting.

SP:

That’s the archetype. The lost penny is the archetype. Yeats had a poem called “Brown Penny.” The same thing. An archetype from one point of view is predecessor, a pre-dater, so to speak. And that gives you permission. That’s a way to look at the archetype.

KH:

So the archetype gives you the permission to write about the personal in ways that are larger than the individual?

SP:

Absolutely.

KH:

I love the poem “Naps.” In that poem I sense the past and present coexist . . . Talk a little about that.

SP:

I think they do . . . I have two poems directly about sleep: One is called “Nobody Sleeps.” I suffer from what’s called . . . terminal insomnia . . . It’s not that I can’t fall asleep . . . but I can’t stay asleep, and usually I work. I read, I don’t write . . . It’s an interesting time to read. It’s what Fitzgerald called the “dark night of the soul.” Three a.m. You really see in a way you don’t see at any other time . . .

“Naps,” though, is about being forced to take a nap as a little boy . . . I hated that . . . you’re missing something. And that’s a universal experience . . .

KH:

But that dream life has to invade in other places, other times.

SP:

This is a Keatsian point, too. Poetry is dreaming. You can characterize it as a waking dream . . . but it’s a form of dreaming. It’s a different kind of thinking … or thinking in a different way about what seems to be obvious or apparent or in front of you. . . . Dreaming is a way of making connections you wouldn’t make before. It’s discovery-thinking, seeing in a way you haven’t seen before. That great image of Eliot’s in “Prufrock”— “when the evening is spread out against the sky.” You can see that.

Not like a bowl of flowers, not like a rose, which were the conventions of the time right before Eliot wrote this poem, the post-Edwardian time. But a “patient etherized upon a table.” That was a dream perception . . . It’s the evening that’s the personified figure there, as if evening were a goddess . . . It must have to do with how the light and maybe a flat cloud [are] operating . . . It’s totally discovered, not concocted. Some poor writers never get that distinction. They’re just metaphor-making machines, contriving all the time. It has to be discovered. You really feel in that image that Eliot has made a discovery. It’s profound in that way. It changed poetry . . . But that’s dreaming. That’s poetry.

KH:

How do you feel about being named poet laureate of Maryland?

SP:

It’s a great honor. I was reluctant, frankly, because I have a lot to do . . . All these invitations have been coming in—Go here, go there around the state . . . I had no sense of how many people [there are] involved in the arts in Maryland, how many arts councils there are . . . people coming to me, all caring, passionate people about the subject. That’s heartwarming . . .

Taking part in festivals, giving readings— it’s fun. I like giving readings. But I enjoy the question and answer more than anything else.