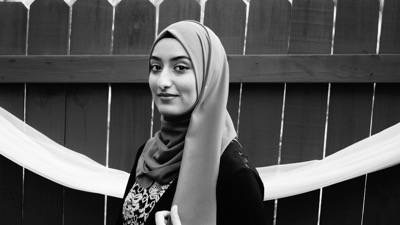

Threa Almontaser

Poetry

Threa Almontaser is a Yemeni-American writer born and raised in New York City. She is a MFA candidate in poetry at North Carolina State University. Her poetry won the 2016 NC State poetry contest, was a finalist for the James Hurst poetry prize, and is a winner of the 9th annual Nazim Hikmet poetry competition. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Track Four Journal, Kakalak Magazine, Gravel Magazine, Day One Journal, Oakland Arts Review, Smokey Blue Literary and Arts Magazine, Atlantis Magazine, and elsewhere. She currently teaches English to immigrants and refugees in Raleigh. Besides writing, Threa enjoys traveling to places not easily found on a map.

A Mother's Mouth Illuminated

PBS taught us English: Sesame Street, Between the Lions, Mr. Rogers.

We passed each learned word between one another—

an umbilical cord of lessons connecting us

to our new terrain. When she probed us for words,

we shrugged her off, You don’t need it. Dishcloth clenched

in her fist, she huffed, No matter how high the hawk flies,

it’s never too late to turn back to the tree.

This is likely a mistranslation. She bled open

book spines with her teeth. Arrowed her mouth

to the Reading Rainbow channel. Rerouted herself

to a place with less mourning, more light.

One evening, she practiced her halting English

to her husband. He stopped her with a hand,

unable to grasp the gibberish, her eager words

tinged with the kinky thickness of a borrowed

speech. Just leave the English to me, he said.

The rats north of 140th street were making him

cruel. We insisted, Don’t worry about it. A woman

in the house all day, you won’t need it. It’s true

she was sequestered on the top floor of our apartment,

spent her days cooking and cleaning, lucky to get a call

card and phone her family back home. What friends

did she have other than us? We were fitting in

ourselves, had no time to be the companion

of a lonely adult who used to think herself fluent,

tongue dined with five-star speeches. From then on,

she kept to herself. Didn’t utter a single word

in any language until we left to work or school

when she fled into the screen. Into the hood

where muppets lived. Then she plugged in her belly-string

and feasted, her whispers desperate for the words,

for the strange lions and big yellow bird,

trying to illuminate their meanings.

We passed each learned word between one another—

an umbilical cord of lessons connecting us

to our new terrain. When she probed us for words,

we shrugged her off, You don’t need it. Dishcloth clenched

in her fist, she huffed, No matter how high the hawk flies,

it’s never too late to turn back to the tree.

This is likely a mistranslation. She bled open

book spines with her teeth. Arrowed her mouth

to the Reading Rainbow channel. Rerouted herself

to a place with less mourning, more light.

One evening, she practiced her halting English

to her husband. He stopped her with a hand,

unable to grasp the gibberish, her eager words

tinged with the kinky thickness of a borrowed

speech. Just leave the English to me, he said.

The rats north of 140th street were making him

cruel. We insisted, Don’t worry about it. A woman

in the house all day, you won’t need it. It’s true

she was sequestered on the top floor of our apartment,

spent her days cooking and cleaning, lucky to get a call

card and phone her family back home. What friends

did she have other than us? We were fitting in

ourselves, had no time to be the companion

of a lonely adult who used to think herself fluent,

tongue dined with five-star speeches. From then on,

she kept to herself. Didn’t utter a single word

in any language until we left to work or school

when she fled into the screen. Into the hood

where muppets lived. Then she plugged in her belly-string

and feasted, her whispers desperate for the words,

for the strange lions and big yellow bird,

trying to illuminate their meanings.