A Buddhist Considers Milestones

by Dick Allen

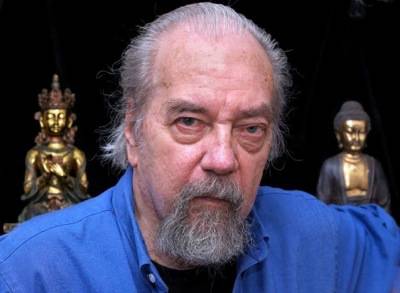

A post in our Milestones series from past contributor Dick Allen.

. . . . The word “mile” always evokes for me the last two lines of Robert Frost’s famous poem, “Stopping by Woods”:

And miles to go before I sleep.

And miles to go before I sleep.

A mile. Sometime in an early grade school classroom I learned there were 5,280 feet in a mile. I measured my normal stride and then reminded myself to count my steps. Thus, I could tell how many miles I’d walked through woods or meadows or along dirt roads. I was extremely ambitious.

A hundred miles. A hundred miles

You can hear the whistle blow a hundred miles

—Peter, Paul & Mary, 500 Miles

However, after college and encounters with Alan Watts and the Zen Buddhist writings of D. T. Suzuki, I’ve never again thought of my life as a series of milestones, although I realize most people do: births, deaths, sports victories, weddings, more deaths, divorces, changes of jobs, moving to new towns and cities, accomplishments, letdowns . . . That way of thinking makes it seem as if one’s life might be like hopping upstream or downstream from one rock to another.

(Sorry about the mixed metaphor. Somehow the milestones got taken from the road to the water.)

As a Buddhist, I’ve come to most often view life as the dharma series of causes and effects, a set of inevitabilities. Milestones are not actual physical entities in this way of thinking. They’re imaginary places or they occur as a part of the process of artistic creation.

So the milestone is the completion of a process rather than a fait accompli physical magazine publication of a poem. To put this another way that may not be familiar to those who don’t give their lives to writing or painting or composing music: I recall finding an exact word for a line of poetry more vividly and acutely than I recall a car that came out of nowhere and smashed into my Chevrolet one long-ago afternoon.

Secondly, each time I come close to realizing, via Buddhism, that the purpose of my life is to simply become aware I’m breathing in and exhaling out,

or become aware of an Emersonian flower in a crannied wall,

or become aware of the way the broom handle feels with my fingers around it as I sweep the floor,

I near (I’m flipping definitions here) the milestone of realizing that what we call “work” is actually an escape from work, an escape from the real and terribly difficult and religious real work of life, which in Buddhism is to realize Nothing is Everything and Everything is Nothing and that people are right to set pots of geraniums on fire escapes.

At the times I’ve come the closest to this realization, I’ve reached what others may well call a negative milestone. I’ve imitated a great mentor who turned down a job in advertising that might have made him rich, decided not to devote his life to politics or college administration, limited his writing only to poetry and poetry connected things, rather than profitable fiction, non-fiction, or editing. He and his wife didn’t move to a large house, or buy an expensive car they coveted, or travel worldwide.

Simplify. Simplify. Simplify, wrote Thoreau.

A friend of mine was extremely successful in the business world. His entire life was devoted to making lots of money for himself and his company—and he did. When he came to the point of being coerced into retirement, he almost literally fell apart. He’d learned to strive, but never to lose himself in a painting or symphony or lily pad. All he could do was drink heavily, smoke pot, watch TV, and divorce his wife.

My “milestones” have been each decision I took along the way into my mid-70s not to be like him.

The real work of life?

Zen might add: Listen to more Bach. Visit museums for Roethkes. Search out New England’s best ice cream stores. Read poems. Write poems. Love McDonald’s cheeseburgers. Touch your toes.

Unlike Frost’s traveller standing in the snow beside his horse and looking into the woods, I believe we actually have no “promises to keep.” Our freedom is ultimate. Because we have no promises to keep, we can paradoxically be enraptured by making promises.

If you miss the train I'm on you will know that I am gone

You can hear the whistle blow a hundred miles.

If you toss a milestone into a lake, you will hear it splash before it sinks and is seen no more.

Dick Allen’s new book is Zen Master Poems, published by Wisdom House/Simon & Schuster in late 2016. He has published eight previous poetry collections. His poems have been included in six of The Best American Poetry annual volumes. Allen’s poems have been featured on Poetry Daily and Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac and in Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry. Allen was the Connecticut State Poet Laureate from 2010-2015.

Dick Allen’s new book is Zen Master Poems, published by Wisdom House/Simon & Schuster in late 2016. He has published eight previous poetry collections. His poems have been included in six of The Best American Poetry annual volumes. Allen’s poems have been featured on Poetry Daily and Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac and in Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry. Allen was the Connecticut State Poet Laureate from 2010-2015.